Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk:

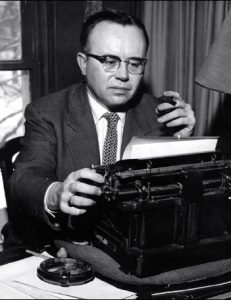

a curated selection of Russell Kirk’s perennial essays

A Note from the Editor

During a commencement address delivered at La Lumiere High School in 1986, Russell Kirk remarked, “Spiritually and politically, the twentieth century has been a time of decadence. Yet as that century draws near to its close, we may remind ourselves that ages of decadence often have been followed, historically, by ages of renewal.” He went on to speak of the moral fortitude which would be required in the graduates’ lives, in words that resonate today.

“You will not need to be rich or famous to take your part in redeeming the time: what you need for that task is moral imagination joined to right reason. It is not by wealth or fame that you will be rewarded, but by eternal moments: those moments of existence in which, as T. S. Eliot put it, time and the timeless intersect.”

What Is All This?

Commencement Address, La Lumiere High School, 1986

Once upon a time I was seated in an automobile passing rapidly along the broad highway that runs between Grand Rapids and Kalamazoo. My companion in the back seat was the very young person who today is among this school’s graduates: Miss Cecilia Abigail Kirk. For some miles, that highway sweeps grandly through a tranquil landscape of fields and woods, apparently untouched by human hand and innocent of human dwellings; it is somewhat eerily empty, as if it were outside of Time. My small companion looked meditatively upon this prospect, and at length inquired of me, with rather a wry curiosity, “What is all this?”

She might have put the question, “Are we in that usual world of ours, or are we out of it?” For it was that sort of landscape, and a silent day, and our car solitary on the highway. Or she might have asked, pertinently, “What are we doing here?” Or “How do we distinguish reality?”

I trust, young ladies and gentlemen, that during your years at La Lumiere you have fallen into the habit of asking yourselves and your friends, from time to time, just such questions. For as Socrates said, the unexamined life is not worth living. The more fully developed a human being is, the more often he asks such questions.

And commencement day is a particularly important occasion for inquiring of the world, “What is all this?”

G. K. Chesterton wrote once that we can understand the human condition only through the medium of parable; it was so that Jesus taught. Permit me to offer you a parable on this day, so eventful for you. I am sure that most of you, at some stage of life, have read or have had read to you C. S. Lewis’ charming series of parables about the battle of life, which he published under the general title of The Chronicles of Narnia. No children’s books in this century have been more influential than the Lewis volumes, which is a reason for us to be hopeful about the twenty-first century. It is from the fourth book of those Chronicles, The Silver Chair, that I draw my parable.

In that book, an enchanted prince and his friends are held captive in enormous caverns far below the surface of Narnia. The Witch-Queen of Underland nearly succeeds in persuading her captives that no “Overworld”—the Overworld being the sunlit reality that you and I know—ever has existed, insisting that the lamps of her own subterranean realm are the only source of illumination; that there is no sun.

“When you try to think out clearly what this sun must be, you cannot tell me,” the Witch-Queen reasons. “You can only tell me that it is like the lamp. Your sun is a dream; and there is nothing in that dream that was not copied from the lamp. The lamp is the real thing; the sun is but a tale, a children’s story.” So cunning is the Witch that she induces the captives to repeat after her, “There is no sun. . . . There never was a sun.”

In our time, ladies and gentlemen, many voices have been declaring, in effect, “There is no sun.” A multitude of writers and professors and publicists and members of the class of persons commonly styled “intellectuals” gloomily instruct us that we human beings are no better than naked apes, and that the mind is merely an imperfect organic computer, and that consciousness is an illusion. Such persons insist that life has no purpose except sensual gratification; that the brief span of one’s physical existence is the be-all and end-all. Such twentieth-century sophists have created out of their murky cave of the intellect, an Underland; and they endeavor to convince us all that there is no sun—that the world of wonder and hope exists nowhere, and never did exist.

True, my old friend Eliseo Vivas wrote once that “It is one of the marks of human decency to be ashamed of having been born into the twentieth century.” Spiritually and politically, the twentieth century has been a time of decadence. Yet as that century draws near to its close, we may remind ourselves that ages of decadence often have been followed, historically, by ages of renewal. You graduates of 1986 will be little more than thirty years old, most of you, when the twenty-first century of the Christian era begins. Endowed with what you have learnt at La Lumiere, and fortified by the habits you have acquired here, every one of you may do something important to redeem the time.

What can you do to commence redeeming the time—that is, to raise up the human condition to a level less unworthy of that the Author of our being intended for us? Why, begin by brightening the corner where you are; by improving one human being, yourself, and helping one’s neighbors. Thus are formed what the early Christians called “the colonies of God.” For such opportunities and responsibilities your schooling at La Lumiere has helped to prepare you.

You will not need to be rich or famous to take your part in redeeming the time: what you need for that task is moral imagination joined to right reason. It is not by wealth or fame that you will be rewarded, but by eternal moments: those moments of existence in which, as T. S. Eliot put it, time and the timeless intersect. In such moments, you may discover the answer to that immemorial question, “What is all this?”

Let me try to enlarge upon these sibylline phrases of mine concerning time and the timeless. Twenty years ago, my wife and I dined in Los Angeles with the most learned and lively of all Jesuits in my lifetime, Father Martin D’Arcy, historian and apologist. My wife, Annette, asked Father D’Arcy about the nature of Heaven.

Heaven, he replied, is a state of being in which all the good moments of one’s earthly existence are forever present, whenever desired—and not in memory merely, not re-enacted merely, but in their original fullness and freshness, outside of Time. Hell, on the contrary, is a state of being in which all the evil moments of one’s life are forever present, against one’s will.

Thus you and I create our own Heaven and our own Hell. The informed Christian knows that his every decision, here below, is irrevocable; that moral choices are for eternity. Heaven is not a fantasy-land where the soul gets a better job and makes new friends. If only you and I could remind ourselves, every day, that we are even now in eternity; that our actions of anger or lust or violence endure forever; but that our actions of generosity or love or forgiveness will be with us beyond the end of Time—why, how immensely better men and women you and I would be! At the very least, how much we would save our years from becoming, in Eliot’s lines, “the sad waste time / Stretching before and after.”

What is all this? Why, this present realm of being, in which your consciousness and my consciousness are aware of reality, is a divine creation; and you and I are put into it as into a testing ground—into an arena, if you will. As the German writer Stefan Andres puts it, “We are God’s Utopia.” You and I are moral beings meant to accomplish something good, in a small way or a big, in this world. Your schooling at La Lumiere has given you some light by which to guide yourself in this endeavor. That is the primary reason why this school was founded, and some of that radiance will remain with you when you may have forgotten nearly everything specific that you studied at La Lumiere.

The old Stoics taught that some things in life are good, and some are evil; but the great majority of life’s happenings are neither good nor evil, but indifferent merely. Wealth is a thing indifferent, and so is poverty; fame is a thing indifferent, and so is obscurity. Christian doctrine inherits from Roman Stoicism, in part, this understanding of how to live a life. Shrug your shoulders at the things indifferent; set your face against the things evil; and by doing God’s will, find that peace which passeth all understanding.

How do we know these postulates to be true? Why, by the common sense and ancient assent of mankind—that is, by hearkening to the voice of old authority, the voice of what Chesterton called “the democracy of the dead.” I think of what John Henry Newman wrote about Authority in 1846: “Conscience is an authority; the Bible is an authority; such is the Church; such is Antiquity; such are the words of the wise; such are hereditary lessons; such are ethical truths; such are historical memories; such are legal saws and state maxims; such are proverbs; such are sentiments, presages, and prepossessions.” Believe what wise men and women, over the centuries, have believed in matters of faith and morals, and you will have a firm base on which to stand while the winds of doctrine howl about you.

This counsel that I offer you will not guarantee your winning of any of the glittering prizes of modern society; for those too are among the things indifferent, and some of them are among the things evil. Yet this counsel from a writer who has seen a good deal of the world may help you on the path toward certain eternal moments, when time and the timeless intersect. What happens at such timeless moments, such occurrences in eternity? Why, quiet perfect events, usually: among them the act of telling stories to one’s children, or reading aloud to them.

What is all this? I have found it to be a real world, sunlit, in which one may develop and exercise his virtues of courage, prudence, temperance, and justice; his faith, hope, and charity. You will take your tumbles in this world, which can be rough enough in our age, Lord knows; but the disciplines of this school have taught you to recover gracefully from a tumble, without many tears. It is a world in which there is so much in need of doing that nobody ought to be bored. For young Americans especially, this is a world of high opportunity.

What advice do I offer you? Why, do not mistake a subterranean lamp for the sun. Do not mistake a witch-queen for Our Lady. Do not fancy that the sorry policy of Looking Out for Number One will lead you to Heaven’s gate. Do not fail to remind yourselves that consciousness is a perpetual adventure. Do not forget the source of Light.

All this creation about us is the garden that we erring humans were appointed to tend. Plant some flowers in it, if you can, and pull some weeds. If need be, draw the sword to defend it. The school of Light has sent you on your way, and I wish you all good traveling in your progress toward the Light Eternal.

Copyright © The Russell Kirk Legacy, LLC

Classic Kirk:

Classic Kirk: