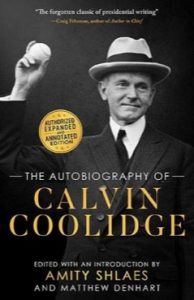

By Calvin Coolidge, edited by Amity Shlaes and Matthew Denhart.

ISI Books, 2021.

Paperback, 239 pages, $22.

Reviewed by Anthony Hennen

Andrew Jackson and Theodore Roosevelt have seen a revival of sorts on the right in recent years, yet Calvin Coolidge has gone perennially overlooked. Given the bellicosity of Donald Trump, it’s not surprising. Coolidge, however, deserves our attention.

Coolidge is a standard-bearer for a certain strand of American conservatism: A belief in the importance of institutions, the value of free markets without an undying faith in them, and dignity for the common man to control his life rather than fund the excesses of his government.

With an expanded edition of Coolidge’s autobiography recently published by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, now is the time to give the 30th president another look.

Coolidge as president from 1923–1929 was a model for a clear vision of civic duty and faithful service to the republic, believing in the importance of America rather than using the bully pulpit to shape the country in his own image.

He was a statesman, not an ideologue. His beliefs were shaped by his experiences as a lawyer, a small-town mayor, a state senator, a governor, and a vice president. It is not an abstract belief system that motivated Coolidge, but wisdom gained through the practice of political life. Well-known for his reluctance to bloviate, “Silent Cal” was nonetheless a well-regarded speaker in his day. He took to the new medium of radio with gusto; a book of his speeches bolstered his reputation when he was governor of Massachusetts.

His willingness to oppose the Boston police strike in 1919 brought him to national attention. Coolidge noted that “It was beginning to be clear that if voluntary associations were to be permitted to substitute their will for the authority of public officials the end of our government was at hand.” Thus, his famous telegram in response to labor leader Samuel Gompers: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

Coolidge’s role in putting down the police strike was shaped by his understanding of the American system of government: it existed as a government of the people, by the people, and for the people. No one person could claim to be above the institution in which they served.

Upholding that system was vital. Coolidge was quick to consult the law and act accordingly. “Free government has no greater menace than disrespect for authority and continual violation of law,” he once told Congress. Personal character and a respect for law was paramount. “Nothing is more dangerous to good government than great power in improper hands,” he said.

Humility wasn’t only a sign of good character—it was a way to protect the American system: “It is a great advantage to a President, and a major source of safety to the country, for him to know that he is not a great man. When a man begins to feel that he is the only one who can lead in this republic, he is guilty of treason to the spirit of our institutions,” he said.

Coolidge understood that he had a role to play in preserving an institution he inherited. It was not his place to subvert tradition and custom for his own ends, no matter how noble he thought they were. Instead, he was to act on behalf of the American people, as the Constitution authorized.

His experience as a legislator and an executive taught him the practical importance of remaining faithful to institutions. The power they bestowed upon him could also lead him to ruin. The moral failure on an individual level would harm the nation, and the awe-inspiring power a president holds endangers him, as he notes near the end of his autobiography:

It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers…. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless and arrogant.

As power attracts the weak and corrupts them, choosing leaders who value wisdom and restraint acts as a preservation mechanism. Flout the importance of moral character, and liberty and economic prosperity are threatened.

Coolidge’s economism was informed by his Vermont upbringing and a certain “New England trait of great repugnance at seeing anything wasted,” inherited from his father, he noted. This Puritan state of mind did not make him a miser. On the contrary, it was deeply rooted in respect for the dignity of the common man:

Wealth comes from industry and from the hard experience of human toil. To dissipate it in waste and extravagance is disloyalty to humanity. This is by no means a doctrine of parsimony. Both men and nations should live in accordance with their means and devote their substance not only to productive industry, but to the creation of the various forms of beauty and the pursuit of culture which give adornments to the art of life.

Economic growth is not an end to pursue for its own sake. Coolidge kept the government small because he agreed with Thomas Jefferson’s “faith in the people and his constant insistence that they be left to manage their own affairs.” Expertise was no substitute for experience. “In his theory that the people should manage their government and not be managed by it, [Jefferson] was everlastingly right,” he wrote.

Industry and prudence frees a nation to pursue the beautiful things of life and preserves man’s autonomy. It’s an implicit check on the conniving of a government that would treat him as submissive, rather than as a citizen.

It should be noted that Coolidge cut federal spending and reduced the debt by one third by the time he left office. He cut taxes, but always tied them to budget cuts. The wealthy paid a larger share of federal taxes by the time Coolidge stepped down.

Coolidge’s outlook may be shared by fewer people today, but it resonated with voters in the 1920s, especially as the radicalism of the early twentieth century lost its luster. “The country had little interest in mere destructive criticism. It wanted the progress that alone comes from constructive policies,” Coolidge wrote. A government under a leader who knew his limits was not weak or anemic. Through restraint, Coolidge preserved American liberty while faithfully governing its people. His view was not concerned with doing too much or too little—what was important was faithfully carrying out his duties as the Constitution allowed.

Yet, a revival in Coolidge’s reputation would only go so far. More than a loss of Calvin Coolidge’s civic education, American society has become more systematized. The opportunity for someone like Coolidge to rise to a leadership position from humble beginnings has shrunk.

Coolidge got his start in politics as a young lawyer, but he didn’t attend law school. Instead, after graduating from Amherst College, he apprenticed at a small law firm to read the law. He was not stymied by lacking a credential that laundered young people through a byzantine system. He worked to gain knowledge, and then demonstrated it and was admitted to the bar. Coolidge then gained political experience on the local and state levels before rising to federal office.

“It is a very old saying that you never can tell what you can do until you try. The more I see of life the more I am convinced of the wisdom of that observation. Surprisingly few men are lacking in capacity, but they fail because they are lacking in application,” Coolidge wrote. “Any reward that is worth having only comes to the industrious.”

Calvin Coolidge’s influence is sorely missed today. He represents an American vision that rejected celebrity and power in favor of humility, the stability of institutions, and the forgotten man. His life was a defense of the greatness of the American tradition: a land of opportunity and a republican belief in human dignity and equality.

Anthony Hennen is managing editor of the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal and managing editor of expatalachians, a journalism project covering the Appalachian region. Follow him on Twitter: @anthonyhennen.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!