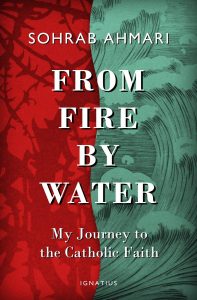

by Sohrab Ahmari.

Ignatius Press, 2019.

Hardcover, 240 pages, $23.

Reviewed by Matthew Hennessey

If you’re going to write a book about your religious conversion it’d better be a great yarn. And if you’re going to write a memoir while you’re still in your early thirties you’d better be a great writer. In From Fire, by Water Sohrab Ahmari has both boxes checked.

A great yarn, according to my definition, traces the arc of a legitimate journey. In the case of a religious conversion, that journey can be from unbelief—or anti-belief—to belief. It can also be from wrong belief to right belief. But it shouldn’t be a short journey, from, say, a little belief to a little more. A great yarn is the kind of thing that doesn’t happen every day. Ahmari was born Muslim in Iran. Before he took his current job as op-ed editor of the New York Post, he was a writer for Commentary, a neoconservative magazine with a stated interest in “the future of the Jews, Judaism, and Jewish culture in Israel, the United States, and around the world.” That’s the kind of thing that doesn’t happen every day.

Ahmari is a precise and evocative writer, which makes From Fire, by Water easy reading and good reading. Casting an unsentimental eye on his home country, he calls Iran a “land of conspiracy and denunciations,” where the national character alternates between burning ideological rage and mournful nostalgia. Ahmari left Iran, with his mother, at the age of thirteen in 1998. Most Western readers will find the picture he paints of life under the mullahs fascinating, not because the details of daily existence are so foreign but precisely because they aren’t. Kids go to school, parents go to work, grandparents tinker in the garage. Boys fight in the schoolyard; their parents force them to make up. People make small sacrifices even as they dream big dreams. It’s just life, the kind of life you might lead yourself if you happened to have been born in a very different place, a land smelling, as Ahmari puts it in his precise and evocative way, of “dust mingled with stale rosewater.”

Childhood can be bumpy no matter how it smells where you grow up. As the only child of intellectual parents who didn’t really get along—Ahmari says his middle-class family was “essentially unhappy”—young Sohrab became a reader, a seeker, a thinker, and a dreamer. Mostly he dreamed of the United States of America, the “Great Satan” of the theocrats’ political imagination. He was transfixed by the optimism and individualism of American pop culture. He wanted to live where they made movies like Star Wars and crafted spectacles like WrestleMania. He had an uncle in Utah, so it was within the realm of possibility that he would one day break away from the complicated, uncomfortable country of his birth: “America stood at the forefront of the modern and the rational, and that was where I belonged.” He imagined the U.S.A. would lift up and celebrate a bright, creative kid, turning him into a bright, creative adult with a bright, creative future. “In the Western imagination,” he writes, “the individual mattered as an individual.”

Not so in the Islamic Republic. Irrationality reigned over the dust and rosewater. Religion teachers railed against Western decadence but watched American blockbuster movies behind closed doors. The morality police were feared but easily bribed—with money, with contraband videos, or with wine. The Shia Islam practiced and professed by most Iranians didn’t comport with the Ahmari family’s “liberal sentimental ecumenism.” The irrationality of Iranian society forced people into a dual existence—one public, one private. Young Sohrab revolted against the duality, ultimately concluding that God didn’t exist and that Islam “was synonymous with law and political dominion without love or mercy.” When he and his mother won their green cards, they hastily decamped for Logan, Utah, a Mormon community about eighty miles north of Salt Lake City.

That detail alone has the makings of a good yarn.

The culture was naturally a shock. Ahmari and his mother lived in a trailer park, and the bright, creative boy suffered the pain of learning that dreams sometimes come true in unexpected ways. The real America was very far from the Hollywood version that had taken root in his mind. Here high school life revolved around “athletics (football especially), dances and dating, and Mormonism—none of which interested me and some of which positively repulsed me.” The teenage Ahmari had an intellectual streak and, compared with his new classmates, was something of a prude. His alienation meant his American fetish “quickly morphed into anti-Americanism.” He became a teenage Marxist and fell in with a small band of class-conscience anti-capitalist misfits at the Salt Lake chapter of a pathetic-sounding outfit called the Worker’s Alliance. “With Marxism, I could oppose the United States as the evil, capitalist hegemon without having to buy into any of the Shiite mumbo jumbo from the old country,” he writes. “Growing up in a totalitarian society, it turned out, didn’t inoculate me against other totalitarian temptations.”

From Fire, by Water is a story of religious awakening, but the political awakening comes first. After graduating from the University of Washington, Ahmari embarks on a post-college tour in Brownsville, Texas, with Teach for America. There he meets Yossi, an Israeli colleague whose personal integrity and refusal to kowtow to the left-wing pieties of the other young idealists in their midst puts Ahmari on a course toward the political right. He’s “utterly in awe” of Yossi’s commitment to doing the right thing all the time no matter how it is interpreted by those peddling the intersectional values of diversity, redistributive justice, and privilege purging. Yossi insists on discipline in his classroom, which is frowned upon by the TFA cadres but which Ahmari secretly believes is necessary. Yossi refuses to “grade generously,” inviting the disapproval of parents and teachers but earning admiration from Ahmari, who sees the results. The kids in Yossi’s classroom excel while the other kids don’t.

“Yossi’s refusal to countenance a lie—no matter how troublesome the truth—marked a milestone in my moral education,” Ahmari writes. He is soon reevaluating his entire worldview, a process culminating in an “earthshaking realization”: “It suggested that there were gradations of character in all human circumstances. That there was great value in old moralistic notions I used to sneer at. And, maybe, that there were permanent things about what made all people tick.” In short order he finds himself disgusted by his Marxist flirtations. “I wanted nothing more to do with manmade utopias of any kind. In fact, I wanted to rededicate my life to thwarting the utopians.”

Ahmari is a voracious and perceptive reader, and his appetite for books and ideas fuel every step of his journey from budding Marxist to postmodern materialist to classical liberal to Catholic convert. This is an intellectual biography, giving readers an inside look at the incremental and steady effect that articles, novels, magazine pieces, paragraphs, sentences, and words, words, words can have on the construction and constant revision of an engaged person’s view of the world. Remember that young Sohrab’s hope in fleeing Iran was to escape irrationality. As an adult he follows where his rational mind leads: from Friedrich Nietzsche to William S. Burroughs, from Albert Camus to Arthur Koestler, from Leo Strauss to Pope Benedict XVI.

Each step in his intellectual development leads him ever closer to the most troublesome truth of all—the cross.

Ahmari’s rode to Rome runs through New York City, where he catches on as an editorial writer at The Wall Street Journal (we never crossed paths during his tenure), and London, where he is catechized by a priest at the famed Brompton Oratory. The latter chapters detailing Ahmari’s religious conversion are brilliantly rendered and will, as Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput writes in the foreword, “stay with the reader for a very long time.” But before he gets anywhere near the baptism he so desires, Ahmari takes readers on a chapter-length detour to Turkey, where he reports on his attempts to enter Europe alongside refugees during the 2016 migration crisis for a Journal story. He seems to view this trip as a final glimpse at the depths of human darkness before the new dawn of his Christian life but it feels slightly out of place. Like the rest of From Fire, by Water, the Turkey chapter is precise and evocative, but it’s a detour, interrupting momentarily the forward motion of what is otherwise a great yarn.

Matthew Hennessey is deputy op-ed editor for The Wall Street Journal.