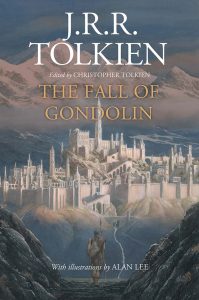

by J. R. R. Tolkien,

edited by Christopher Tolkien.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Ben Reinhard

The Fall of Gondolin is, appropriately enough, the story of endings: the end of the mythical kingdom, to be sure, but also the end of an era in Tolkien studies. Tolkien’s own imaginative world was dominated by his four “Great Tales” (the Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, the Fall of Gondolin, and the Voyage of Eärendel); the last fifty years of Tolkien publishing have been dominated by the able curatorship and editorship of Christopher Tolkien. With Gondolin, the old order comes to an end: it is both the last Great Tale to be published in its entirety and “indubitably” the last edition to be produced by the younger Tolkien. We now enter the third age of Tolkien publications; one can only hope that this new era, whatever it brings, will be in some way worthy of the second.

If Gondolin is indeed the end, it is a fitting send-off: easily the most satisfying of the recent Tolkien editions. I’ve been critical in the past of some of these volumes for inconsistent editing and a baffling refusal to give complete versions of the texts they present. This volume avoids these pitfalls, presenting in their entirety the successive versions of the story, together with a concluding essay on the “Evolution of the Story.”

The results are staggering. The juxtaposition of the various versions, from the 1916 “Tale of the Fall of Gondolin” to the “Last Version” of 1951, allows the reader to see, as nowhere else, the growth of Tolkien’s Great Tale—and the growth of the author’s powers along with it. The development of the story itself (the addition of some elements, the removal of others, and the reconciliation of inconsistencies) is ably illustrated in Christopher Tolkien’s valuable essay on “The Evolution of the Story,” and need not be revisited here. The growth of Tolkien as storyteller is, however, another matter entirely.

The tales presented in this volume take us from the very beginning of Tolkien’s literary career to its peak. The first full version of the story, the 1916 “Tale,” was originally printed in the second part of The Book of Lost Tales and is of a piece with the rest of book: it properly belongs to the Cottage of Lost Play (a storytelling device Tolkien used in The Book of Lost Tales). Tolkien’s world is as yet undeveloped, and though it contains many of the creatures of his later fiction—elves, orcs, dragons, and balrogs—they have not yet reached their final form. Indeed, they preserve some elements of traditional folklore that Tolkien would later repudiate: as, for instance, the traditionally small stature of the elves (see, for instance, Gondolin 53; compare The Book of Lost Tales: Part One, 32). Characters have names that belong to fairytale (e.g. Littleheart) or that lack the linguistic consistency and euphony we expect from Tolkien (e.g. Rog). We still have a long way to go to the world of The Silmarillion or The Lord of the Rings.

Some of the defects in this early “Tale” are, however, a net benefit for our understanding of Tolkien’s legendarium. The comparatively artless composition of the story leaves many seams showing—a disappointment to the aesthetician, maybe, but a treat for the student. It is common knowledge that Tolkien’s imagination was formed throughout his career by his academic study and by his Catholic faith, but in his mature works his artistry is often so skillful that its roots are concealed. This is not yet the case in the “Tale,” however, and as a result Tolkien’s imaginative debts are obvious. So for instance the Lord of the Waters, Ulmo, is in this version heavily indebted to the classical Neptune—complete with an undersea palace, the music of horns, and a ride in a chariot drawn by sea creatures (compare, for instance, Gondolin 45 with Aeneid I.124–56). The debate between Tuor and Turgon on pp. 56–7 owes much—up to and including its chiastic structure—to council scenes from Greek and Roman epic. Most importantly, the fall of Gondolin itself is a transparent re-presentation of the fall of Troy as anticipated in the Iliad and recounted in the Aeneid. The connection between Gondolin and Troy is encouraged, indeed demanded, by the text itself: as the narrator Littleheart says, the fall of Gondolin “was the most dread of all the sacks of cities upon the face of Earth. Nor Bablon, nor Ninwi, nor the towers of Trui … saw such terror as fell that day” (Gondolin 111).

Once the relationship is recognized, endless similarities can be supplied. Each work (Iliad, Aeneid, the “Tale”) gives a hero (Hector, Aeneas, Tuor) who must balance his duty to protect his wife (Andromache, Creusa, Idril) and son (Astyanax, Iulus, Eärendel) with his desire to heroically protect his city; each city has a lord (Priam, Turgon) who refuses divine counsel and stubbornly trusts to the pride of his city; each assault features crashing towers and animals bearing enemy soldiers in their bellies—the Trojan horse for the Aeneid, and orc-bearing dragons for the “Tale” (see Gondolin 69ff). As the city falls, the survivors escape by a secret way to the sea.

For all this, the “Tale” is not a straightforward retelling of the fall of Troy—and the differences give us a valuable glimpse at Tolkien’s moral imagination and visionary creativity. So, for instance, the tale of the fall of Troy is dominated by three villains: the liar Sinon, who betrays the Trojans; the brutal warrior Pyrrhus, who slays Priam and takes Andromache as his sex slave; and the amoral and calculating Ulysses, who casts Astyanax from the battlements of Troy. In the “Tale” these three villains coalesce into one—the dark elf Meglin—who betrays Gondolin to Morgoth, attempts to carry off Idril, and intends “to take Eärendel and cast him into the fire beneath the walls” (Gondolin 80). But unlike the classical Hector—or even pius Aeneas—Tuor never wavers in his duty, putting the safety of his family over the prospect of a glorious death in a doomed defense. As a result, the traitor Meglin fares in Gondolin as Ulysses ought to have fared in Troy: the new Hector catches him in the act, and Meglin is thrown from the ramparts himself. His family secured, the new Aeneas leads child and wife safely from the sack of the city to a dim and distant new hope.

The rescue of Eärendel brings us to what is, perhaps, the central animating idea of all of Tolkien’s works: the hope “beyond the walls of the world,” as “On Fairy Stories” has it. Eärendel is simply Tolkien’s most transparent Christ figure. His name and basic character are drawn from an Old English paraphrase of the fifth O Antiphon, and his literary descent is borne out in his role in the Silmarillion. Both man and immortal, he intercedes with the gods to win mercy for his exiled and sinful people; in the apocalyptic War of Wrath, he defeats the great dragon and secures the eucatastrophic victory. Some versions of the tale dispense with any typological subtlety whatsoever: in the 1951 version, Eärendel has become “a hope beyond thy sight, and a light that shall pierce the darkness” (Gondolin 166).

The hope embodied in Eärendel marks a significant departure from Tolkien’s classical models: for all their differences, both the Iliad and the Aeneid root their hopes, such as they are, firmly in this world. It also introduces the central moral conflict of the story: a distant hope from outside the world can be hard to credit; Turgon and his people prefer, as he says, “to trust to ourselves and our city” (Gondolin 57). The exiles mistake the land of their sojourn for the promised home. The conflict between the great otherworldly hope and its counterfeit in this-worldly satisfaction is the great unifying theme in the tale’s development, and remains consistent through the successive versions (see, for instance, Gondolin 77, 124, 133, 138).

Much besides changes. With each iteration, the story is refined, and its debt to classical models—though still undeniably present—is obscured. As this happens, however, the tale takes on a power and consistency all its own, forged in the fires of Tolkien’s imagination.

One passage will have to suffice to illustrate the growth of Tolkien’s powers. In the earliest version, Ulmo is

robed to the middle in mail like the scales of blue and silver fishes; but his hair was a bluish silver and his beard to his feet was of the same hue, and he bore neither helm nor crown. Beneath his mail fell to the skirts of his kirtle to shimmering greens, and of what substance these were woven is not known, but whoso looked into the depths of their subtle colours seemed to behold the faint movements of deep waters shot with the stealthy lights of phosphorescent fish that live in the abyss (45).

A passable image, and containing flashes of what would become Tolkien’s mature style. But the 1951 version is something else entirely. In this final version, Tuor beholds Ulmo rising as “a mighty king”:

A tall crown he wore like silver, from which his long hair fell down as foam glimmering in the dusk; and as he cast back the grey mantle that hung about him like a mist, behold! he was clad in a gleaming coat, close-fitted as the mail of a mighty fish, and in a kirtle of deep green that flashed and flickered with sea-fire as he strode slowly towards the land (164).

Similarities in imagery and diction make the dependence of the latter on the former obvious—but here we see Tolkien at the heights of his creative powers. This is the full, mature prose of the Lord of the Rings, at once more formal and dignified and more clear and concise than the youthful Tolkien’s experiment above (indeed: careful readers may detect syntactical similarities between the description of Ulmo and the portrayal of the Witch King in “The Siege of Gondor,” composed around the same time). In this mature version, excesses in imagery and color have been trimmed back; the inexcusably scientific “lights of phosphorescent fish” has been replaced by the properly wonderful “sea-fire”; stronger stress patterns and alliteration have been added throughout. The result is a vision worthy of Wordsworth’s Proteus and Triton, and we get a glimpse of what might have been.

The unfinished portions are magnificent; one can only imagine what the “Last Version” might have become: another work to the scale of Lord of the Rings? Something yet greater? Not for nothing did Christopher Tolkien describe the failure to complete the 1951 version as “perhaps the most grievous of [Tolkien’s] many abandonments” (Gondolin 203; compare Book of Lost Tales: Part Two, 203). And so the tale of Gondolin ends in words of its first narrator, Littleheart son of Bronweg: “Alas for Gondolin!”

Ben Reinhard is an assistant professor of English Language and Literature at Christendom College, where he teaches courses in classical and medieval literature. His research interests include Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, medieval saints’ lives, and modern translations of Old English poetry.