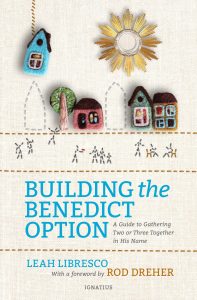

by Leah Libresco.

Ignatius, 2018.

Paperback, 163 pages, $17.

Reviewed by Gracy M. Olmstead

Nobody was meant to be a loner.

In the Garden of Eden, God said that it was “not good for man to be alone.” Aristotle writes in his Politics that “Man is by nature a social animal; an individual who is unsocial naturally and not accidentally is either beneath our notice or more than human.”

Yet as Leah Libresco points out in the beginning of her new book, Building the Benedict Option, many of us slip into isolation without even trying: “the atomized nature of the modern life makes it possible to become a hermit unintentionally.” This is a problem, she adds, because “living one’s faith alone is the religious equivalent of trying to run a marathon without so much as a jogging habit in preparation.”

Leah’s book is a followup and response of sorts to Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, published last year. Dreher himself wrote a foreword, but it’s important to note that Building the Benedict Option is a standalone volume and can be enjoyed without having read the former book. In his book, Rod considers the increasingly secular culture surrounding Christians (especially American and European Christians), and suggests that we adopt the rhythms of community and spiritual discipline adopted by Benedictines following the fall of the Roman Empire. In a fractured and frayed world, intentional Christian fellowship of this sort would provide hope and succor.

Leah’s book considers just how to kickstart this sort of deeply embedded, giving community in the modern era. While many of Rod’s critics have (despite his strong protests) seen his “BenOp” as an insular idea, Leah’s blueprint is anything but insular. She envisions and proposes a community that makes its faith and worship as public and outreach-oriented as possible. Perhaps this tendency toward active outreach stems, at least in part, from Leah’s urban setting: whereas Rod Dreher’s BenOp examples often seemed more drawn from rural, agrarian sorts of community, Leah applies the tenets of Benedictine living to her Washington, D.C. and New York City homes. Here, we do not see Christians living in an isolated setting, seemingly shunning the outside world. Instead, Leah writes about litany-of-saints picnics in the park, debates on the roof of her apartment building, poetry and Shakespeare readings that draw in believers and nonbelievers, and providing casseroles and cookies for the spiritually and physically hungry. Leah asserts that the BenOp isn’t about a Christian withdrawal: it’s about cultivating Christian vibrancy and transparency wherever we are planted.

At the beginning of the book, Leah compares intentional Christian community to the work of mending nets: “My friend Bryce pointed out that in the Gospel of Matthew, we see a little more about what it means to be fishers of men. In a message to a group I belong to, Bryce said, ‘If fishing is a metaphor for the Church’s work (“I will make you fishers of men”), it’s noteworthy that we see the Apostles not only “casting a net” (4:18) but also “mending their nets” (4:21). If casting represents preaching, spreading the gospel, suffering martyrdom, etc., what does mending represent?’”

The Benedict Option, Leah suggests, “is a way to mend nets and to prepare to cast them out again. Trying to thicken my community and open my home gives me the chance to live my faith more openly and truthfully.”

In Leah’s conception, the BenOp encourages Christians to do together what one can (but should not always) do alone—including, most prominently, prayer; doing publicly what one can do privately; making the home a center of gravity (a place of solace and “net-mending”); and fostering welcome for strangers both inside and outside of the faith.

Leah’s emphasis on prayer and hospitality are strong throughout. I am not Catholic, but I deeply appreciate and admire Leah’s emphasis on community prayer—and feel it’s something Protestants do not practice as well as they ought. Throughout this book, I saw many ways in which Catholicism helps safeguard against insular, private Christianity. Leah writes of praying with her rosary on the subway, or hosting a litany-of-saints picnic in the park. What would Protestant equivalents of such public Christianity look like? It’s a question worth pondering. Evangelicals, in particular, tend to neglect prayer—perhaps in large part because they lack a liturgy to support and foster their practice. But as Leah points out,

“For Christians, it is impossible to just be with each other without some space for prayer. Christ tells us that ‘where two or three are gathered in my name, there am I in the midst of them’ (Mt 18:20). Without a structured prayer or a moment of silence or extemporaneous petitions and thanksgiving, we are ignoring the cause of our being. We can’t fully see and enjoy each other without seeing who we are, and my being an adopted and beloved daughter of God is much more the core of my identity than the books I’ve set out on my shelves. To see only the parts of ourselves that are embedded in this world, and to ignore the world to come, is to cut off the most lasting part of who God made us to be.”

This is also what differentiates Leah’s BenOp fellowship from other, more popular forms of Christian fellowship. Potlucks and picnics, youth group events and game nights may abound—but how often do we gather to pray the Night Office or take up a Lenten fast together? We Christians are good at sharing secular traditions together, be it Super Bowl parties or March Madness tournaments; we are not always good at nourishing each other’s faith on a regular basis. Perhaps this, more than any sort of cultural crisis or apocalyptic catastrophe, is a sign of how badly we need the Benedict Option.

The suggestions Leah presents for fellowship and hospitality make it impossible to hide your light under a bushel. In this sense, she soundly refutes the idea that the BenOp necessitates Christian insularity. But more than that, she makes clear that (at least for many of us) our current forms of Christian living are far too lukewarm and comfortable. It could very well be that, in the future, the BenOp—at least this BenOp—is (in the words of G. K. Chesterton) not tried and found wanting, but rather found difficult and left untried. The BenOp Leah wants to cultivate contains a purity and enthusiasm that are impossible to hide. The question then becomes not whether such Christian living would be salutary, but whether we are willing to give ourselves so wholeheartedly to the Gospel and to each other.

Leah’s history—as an atheist prior to conversion, and as an insanely smart writer and mathematician—infuses this book with a zest for the Gospel and a quirky, detail-oriented approach to hospitality. Her methodical guide to launching BenOp events will be a helpful resource to those who might otherwise feel intimidated by the demands necessary to get such a project started.

But Leah makes it clear that this book is only the beginning of her own work in fostering BenOp community. She envisions a future in which Christian families in an urban setting could share townhouses together—sharing meals every day, praying regularly together, and helping care for each other’s families. In many ways, the end goal of this book is a return to an ancient sort of multigenerational living which breaks apart the nuclearization of (Christian and) secular America in order to foster something we’ve lost to the tides of modernity.

“We sing songs together, we break bread, we spill out into the streets in processions all because we live in hope, longing to find our home in heaven with our Lord,” Leah writes. “Too often today, people know our faith primarily by its list of ‘thou shalt nots’, but they should be able to see in our lives some reflection of the One we have said yes to.”

This is what a Benedict Option should display: a joy and zest for the Gospel, a nourishing community, and a delicious hospitality that the world will not just see, but find impossible to resist. In this sense, the mending of nets also becomes the casting—because when we love each other in a world that is starving for love, others will want in.

When Alasdaire MacIntyre wrote that we needed “another, doubtless very different, Saint Benedict,” he probably could not have envisioned Leah Libresco. But she could be just the person he was looking for. She’s at least given us all a wonderful and practical start.

Gracy Olmstead is associate managing editor at The Federalist. Follow Gracy on Twitter @GracyOlmstead.