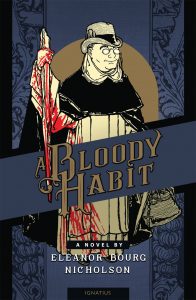

by Eleanor Bourg Nicholson.

Ignatius Press, 2018.

Paperback, 435 pages, $19.

Reviewed by Matthew M. Robare

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: while traveling through central Europe, a modern English lawyer gets entangled in the machinations of a demonic vampire and must call upon aid both natural and supernatural to defeat the creature and save civilization from a foe whose existence that civilization does not accept.

While that is, indeed, in broad terms the plot of Bram Stoker’s classic Dracula, it is also the plot of Eleanor Bourg Nicholson’s new novel, A Bloody Habit (Ignatius, 2018). The novel is, in some respects, an homage to Stoker—every chapter begins with a quote from Dracula and characters make frequent reference to the novel, culminating in Stoker himself making a cameo appearance towards the end. But mostly, it’s a novel of suspense and action, a grand adventure story told with imagination and faith in grace. Thankfully, the intertextuality is handled deftly and does not distract from the plot. In less skilled hands, it could have made things campy or made the similarities seem excessive.

Instead, A Bloody Habit and Dracula are in a kind of dialogue over theology. The Catholic themes of Dracula—the efficaciousness of sacramentals and the Sacraments against the Count and vampirism’s dark mockery of the Eucharist must be set against Stoker’s lack of understanding of Catholicism. Rereading the novel once a year, as I do, Van Helsing’s treatment of the Blessed Sacrament never fails to make me wince or roll my eyes, as his characters commit sacrilege to fight evil and Van Helsing thinks that an indulgence means he has leave to take dozens of consecrated Hosts and carry them about his person. According to Bruno Starrs, Stoker was a member of the Church of Ireland and debates remain about his intentions with the religious symbolism and allegories in Dracula.

By contrast, not only does A Bloody Habit highlight the Catholic nature of the vampire, it provides a Catholic understanding of the vampire. Nicholson’s vampire is a demon who possesses the corpse of a person who is somehow complicit in the process, while other victims have differing degrees of complicity and culpability. Nicholson firmly grounds her vampires in Catholic theology by making them representations of heresy, as well as by the concern demonstrated by the characters regarding culpability the respect due to the vampire’s body. Moreover, the Dominican friars tasked with destroying vampires (itself a nod to the Order of Preachers’ significant role in combating heresy and developing Eucharistic theology and the devotional practice of Adoration of the Eucharist) perform exorcisms and protect victims in convents.

The plot features the modern, more or less agnostic English barrister, John Kemp as he is drawn into a web of Modernism, the Occult, and vampires and their opponents, the Order of Preachers, specifically in the person of Rev. Thomas Edmund Gillory, OP. Kemp becomes involved because he is the lawyer for Edgar Kilbronson in his divorce with his wife, Elisabetta, and is searching for her to take her evidence and recover property Kilbronson accused her of stealing. But the vampire also wants her for his own reasons.

Nicholson is at her strongest in evoking what the late Rev. Andrew Greeley called “the Catholic Imagination”: the “propensity among Catholics to take the objects and events and persons of ordinary life as hints of what God is like, in which God somehow lurks.” Or, in the case of A Bloody Habit, the philosophy of using human beings as means to an end, of seeing life as something to be consumed, takes terrifying, literal form. In reading the novel, one gets a picture, or perhaps a partial reflection, of the real world behind the symbols. Vampires are real, even if they are not undead blood-drinkers.

In addition to the influence of Stoker, A Bloody Habit appears to owe much to J. R. R. Tolkien and G. K. Chesterton. Gilroy, the lead Dominican character, owes something to Gandalf in the way his cheerfulness and compassion cover his power and wisdom; the villain delivers a speech reminiscent of the effect of Saruman’s voice in The Two Towers, and a passage enumerating the number of people setting off to destroy the vampire was like the “Nine Walkers against Nine Riders” passage in The Fellowship of the Ring. The villain is where Chesterton’s influence is felt most strongly; like Lucian Gregory and the anarchists in The Man Who Was Thursday, the villain’s goals are less physical and more philosophical, using science, philanthropy, and social climbing as much as the Occult, hedonism, and people’s desire for power to subvert religion and morality. The appearance of members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn aiding the vampire is not only a great moment in an excellent action scene, but helps to highlight the connection between the ancient heresy represented by the vampire and the new ones promoted by Bentham and Mill or G. . Moore and H. G. Wells.

A Bloody Habit is not without flaws. The beginning of the book reads very slowly without increasing the tension. Even the murder of a minor character—Charles Sidney, who with his knee-breeches and crushed velvet suits seems to be standing in for Oscar Wilde—doesn’t fully get the pace going, although it serves as a better kick-off to the plot. It could also perhaps use more horror. Dracula still manages to terrify after more than a century, but A Bloody Habit takes a little more to get, and keep, going. Other flaws are niggling and perhaps will pass most readers unnoticed: Sidney’s house in Bloomsbury, where some of the action is set, has a large yard and a long driveway, even though that part of London is very densely packed with buildings; the police forensics expert Dr. Lewis is sometimes named Dr. Martin, the protagonist John Kemp is a barrister, but sometimes does the work of a solicitor. Elisabetta Kilbronson is also a disappointment—she is important to driving the plot forward, but never becomes a character in her own right.

However, once the pace picks up, Nicholson’s skill as a writer will carry people through to the end without interruption. It may be too early to add A Bloody Habit to the canon of great vampire stories, but this is only Nicholson’s second novel. Her future books ought to be awaited eagerly on the strengths of this one.

Matthew M. Robare is a freelance writer based in Boston.