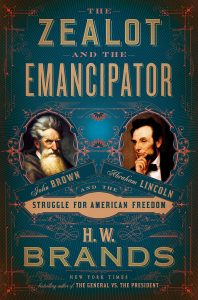

by H. W. Brands.

Doubleday, 2020.

Hardcover, 464 pages, $30.

Reviewed by Carl Rollyson

H. W. Brands has written perhaps his most fluent book, a constantly engaging study of history and biography worthy of the model on which it is built: Plutarch’s parallel lives. In assessing a life, Plutarch argued, one had to have a basis of comparison, a demonstration of how equally famous men had arrived at their achievements or renown in similar and different circumstances, with personalities that can be contrasted and balanced against each other. Plutarch’s aim is not merely to describe lives but to judge them, to weigh their ethical value and to measure their political effectiveness.

Both John Brown and Abraham Lincoln made their mark in the years leading up to and encompassing the Civil War. Bloody-minded Brown struck history first in his raid on Harper’s Ferry, after years of thinking, as Brands puts it, he could “shame the slave holders into abolition by educating young blacks.” In the conflict in Kansas over whether the territory would become a slave dominion or a free, democratic commonwealth, Brown had slaughtered slavers in a rehearsal of his plan to attack a federal arsenal and summon the slaves to open insurrection. Lincoln, thinking slavery no less an abomination, nevertheless temporized, supposing he could corral the recalcitrant South to return to the Union, even after seven of its states declared for secession, by renouncing any intention of abolishing slavery where it already existed. He delayed the final decision for war until the attack on Fort Sumter, not wishing to be seen as the aggressor. Lincoln wanted to keep the Union together even if that meant the perpetuation of slavery. As Brands observes, Lincoln’s objectives were entirely political, no matter his moral condemnation of slavery. For John Brown and his sympathizers, such as Frederick Douglass, the evil of slavery, the immorality of accepting its continued existence, made a mockery of the Declaration of Independence and its affirmation of equality, rendering the idea of the Union nugatory.

Events, as Brands shows, forced Lincoln to become as bloody-minded as Brown. Lincoln knew that at some point in the war he would have to make an emancipation declaration which would free those slaves in the rebellious states. Such a declaration might offend moderates and conservatives, especially in the border states, who did not care about the emancipation of blacks, but manumission would also shore up his support in the ranks of the Radical Republicans, who favored the abolition of slavery. Lincoln believed that with an emancipation declaration, after Union victories, he could draw to the Union lines legions of former slaves promised their freedom who would fight against their former masters. So they did—200,000 of them that Lincoln said were vital to the North’s cause, and without whom the war could not continue above three weeks! With the ex-slaves on his side Lincoln realized he could not fail because they made good soldiers notwithstanding the skepticism of both Northern and Southern military commanders.

Brands binds together the parallel lives of Brown and Lincoln in a wonderful paragraph that is, nevertheless, what you might call the biographer’s sleight of hand, using Frederick Douglass as the adhesive:

If Frederick Douglass heard an echo of John Brown in Lincoln’s second inaugural address, he didn’t mention it. But as one who had known Brown well, Douglass—then or later—must have reflected that Lincoln’s suggestion that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword” sounded chillingly like Brown’s final prediction that “the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

What begins as what Douglass did not mention ends as what he “must have reflected.” I have to say this happens all the time in biography, where the gaps in history and biography are filled in by a writer who cannot bear the abyss of not knowing. The one doing the reflecting, of course, is Brands, who would be on sounder, if less dramatic ground, to simply point out the irony of Lincoln’s words that echo Brown’s call for the violent overthrow of slavery.

It would not be generous to pound away at this shifting of the evidence if Brands did not, on several occasions, resort to theatrics—such as when he describes the wounded Brown, captured by Robert E. Lee no less, in his cell: “The prisoner raised himself on his elbow and picked up his pen.” Or: “John Brown shifted and tried to get comfortable.” Or: “Abraham Lincoln shuddered.” Or several times Brands has Lincoln groaning, or how about “Lincoln looked at the walls of his office.” No doubt, but when, how, is, of course, lost to history and biography. We can imagine Lincoln and Brown doing all these things, but pinpointing them is beyond the biographer’s ken and belongs in historical and biographical novels. Brands writes what might be called figurative history, which will not bother some readers, although others may well prefer what can be literally depicted.

But there are many passages in this book which redeem its Plutarchian purpose and have no need of embellishment. Here is a passage that sums up Brands’s method and insight:

Lincoln himself had raised the issue of blood atonement in his second inaugural address. Now his own blood was part of the reckoning, and his link to John Brown more compelling. Brown had foretold blood atonement while becoming one of the first sacrifices; Lincoln at the time had resisted the concept for his country and scarcely imagined it for himself. But he made decisions whose consequences included a bloodletting far greater than anything Brown had envisioned, and finally his own death. Brown was a first martyr in the war that freed the slaves, Lincoln one of the last.

Sometimes Brands needs only a sentence to show why Brown and Lincoln belong together: “Brown aimed at slavery and shattered the Union; Lincoln defended the Union and destroyed slavery.” That kind of parallel structure reminds me of Samuel Johnson.

Carl Rollyson is the author of The Life of William Faulkner, in two volumes, published in 2020 by the University of Virginia Press.

NEH Support

The University Bookman has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.