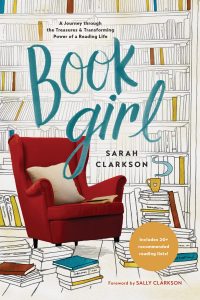

By Sarah Clarkson.

Tyndale Momentum, 2018.

Paperback, 288 pages, $16.

Reviewed by Ashlee Cowles

What does it mean to be a woman who reads? This is the primary question Sarah Clarkson seeks to answer in her wonderful new release, Book Girl. Filled with over twenty recommended reading lists, Clarkson’s latest work is not merely a manifesto for naturally bookish girls and women who need little encouragement to read; it is also a thoughtful reflection on why reading matters as an ennobling, transformational act of true leisure in an era of exhausting entertainment.

I am a lifelong reader. As an undergraduate student, I had an epiphany that now seems obvious, but was startling at the time: not everyone has been shaped by stories. Or at least not by beautiful stories. We’ve all been shaped by a story of some kind—as human beings we cannot escape this fact—but as a young woman I began to notice that when I felt an immediate connection with another person—that special spark, the whispered promise of a kindred spirit—it usually didn’t take long for our conversation to turn to books, of which there were often several shared favorites.

Similarly, when I encounter another person whose imagination hasn’t been shaped by books, there’s often the sense that a sort of chasm exists between us, meaning it will take more time and effort to build the bridge that enables us to understand each other. Perhaps this seems judgmental in an age where personal preference is king, but I don’t think the disconnect is simply a matter of “different interests,” as if reading were another hobby among many possible pastimes.

It wasn’t until I discovered Russell Kirk that I was able to articulate the nature of this gulf—that without a “moral imagination” shaped by the timeless myths and universal stories that allow us to unearth the complexities of the human heart and the sacramental nature of our world, we tend to live isolated within our own private experiences in our own time and place. As a result, we lack the empathy and childlike wonder needed to even see the bridges that might be built between souls.

Yet Clarkson’s writing does not contain a hint of snobbery or trace of condescension, no self-congratulatory sense that being bookish automatically makes one more virtuous or enlightened. Instead, Book Girl is like a warm invitation to a party where it’s impossible to arrive too late. It’s the perfect gift for a teenage girl who voraciously reads the latest “young adult” release but hasn’t yet explored the deeper riches of a reading life, or the young mother who’d rather consume something of substance than scroll through social media during those late-night feedings but doesn’t know where to start.

Book Girl asserts that reading—especially reading fiction—isn’t an escapist activity (unless, as Tolkien said, we are escaping from the many jailers of the modern world), but a deeper encounter with the true nature of reality. Our world is one of tragedy and much suffering—a truth the spheres of Instagram filters and advertising try to deny—whereas great literature always places the human condition front and center. Because of this, Clarkson proposes that a reading woman is ultimately a realist:

She lives in this broken place, and she grapples with the daily stuff of life in a fallen world. Broken bodies, shattered relationships, a world in which wars and flat tires and miscarriages are daily realities—this is her story, and the great works of fiction and theology show her what redemption looks like in ordinary time. (222)

At the same time, the reading woman can see the creative potential of the seed buried deep in the dark ground; she is empowered to walk by faith and see with the eyes of hope, all while cultivating a love that asks us to engage with suffering rather than flee from it:

A woman who reads is a woman who has been prepared to accept the truth that beauty tells, to embrace the good news that imagination brings, the promise of joy that greets us in the happy endings or poignant insights of the novels we love. She has learned to glimpse eternity as it shimmers in story or song, to receive the satisfaction of a happy ending as a promise. She has come to recognize the voice of love speaking in the language of image and imagination and to trust what it speaks as true. (131)

In these passages, Clarkson—a new mom herself—beautifully captures the yearnings of my new mother’s heart in her description of the kind of woman I hope my own daughter will become. When I was pregnant and learned, to my surprise, that my first child would be a girl (I’d had strong “boy vibes”), my initial “Wait, are you sure?” to the ultrasound technician was soon followed by excitement—a fervor centered around stories. Now I had the opportunity to cultivate my own little “book girl,” building a bridge from my heart to hers as we shared in the adventures of Laura Ingalls, the wonder of Anne Shirley, the intelligence of Hermione Granger, and the courage of Lucy Pevensie—not to mention the dozens of other characters I did not have a chance to meet in my own childhood. This enthusiasm and a tone of contagious delight fills every page of Book Girl, turning the reading life into something we get to do rather than something we ought to do. By the end, my own answer to the question, “What does it mean to be a woman who reads?” was this:

A woman who reads is a woman who chooses joy.

Ashlee Cowles is a former Russell Kirk Center Wilbur Fellow, a literature teacher at a classical high school, and the author of the novel Beneath Wandering Stars (Merit Press, 2016).