By Jacob Heilbrunn.

Liveright, 2024.

Hardcover, 264 pages, $28.99.

Reviewed by Chuck Chalberg.

Paul Hollander, wherever he is, need not worry. The best book by far on an American romance with foreign dictators has long been–and remains–his Political Pilgrims. Written in 1981, it chronicled Western intellectuals on the left and their romance with a certain set of totalitarian foreign dictators. And a love at first sight that romance surely was and all too often remained.

Jacob Heilbrunn reverses things in his account of a somewhat different story of romance, as well as a very different set of romancers. As his subtitle reveals, both his romantics and those he alleges are being romanced are on the right.

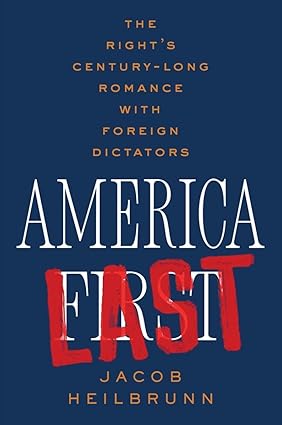

But that’s only the half of it, as the final version of his title reveals. Final version? Well, not really. The official title is “America Last,” but the cover reads “America First” in nice white letters with “LAST” in dark red letters covering much, but not all, of “first.” There apparently is supposed to be some, but very little, doubt that a point is being made.

The point is that those who stand under the banner of “America First” actually put Americans last, since their true concerns, preoccupations, and, yes, romantic interests lie elsewhere. And “elsewhere” for Heilbrunn means such places as Hungary (under Orban), Chile (under Pinochet), Spain (under Franco), Italy (under Mussolini), Portugal (under Salazar), South Africa (under anyone prior to Mandela), various countries of Africa north of South Africa (under any right-wing despots/anti-communist authoritarians), various countries in Central America (under the same), Germany (under the Kaiser and Hitler), and Russia (under Putin, but no one else).

But once again, that’s only the half of it. Heilbrunn’s additional point seems to be that his rightist romantics are always on the lookout for picking up pointers here and there from these foreign dictators regarding the best techniques for dealing with internal dissent—and eliminating it.

This Heilbrunn point is something that he assumes rather than anything that he attempts to prove or flesh out with much by way of evidence. At least that seems to be his operating assumption until his century-long story enters the 21st century. Until then, he simply assumes that Americans who love authoritarians abroad seek to impose authoritarianism at home. Now, at this point in our nation’s history, he seems to be thoroughly convinced that this is the case. But the sweep and contents of the book deal with the romance and the romancing, and not with these romancers and their, shall we say, unromantic plans for their fellow Americans.

Yet Heilbrunn wants his readers to believe that everything about this romance has been building toward a very unromantic conclusion. What might have begun as a series of star-struck romances has been gradually morphing into something other than that. In other words, this book is not just an accounting of the wonders these dictators have accomplished for their own people, at least in the minds of these American romantics; it’s also the mind of Jacob Heilbrunn wondering what these romantics have long had in store for their fellow Americans.

Heilbrunn’s ultimate villains are those he labels the “new authoritarians” of relatively recent vintage. More specifically, they include anyone who falls under the general heading of “conservative populism.” The first time Heilbrunn uses that term is about Christopher Caldwell, who “embraced (it) early on,” especially with his 2009 book Reflections on the Revolution in Europe.

Other named names in the scribbling class include Rod Dreher, Sohrab Ahmari, Patrick Deneen, and Adrian Vermeule. Unnamed names would include any exponent of integralism, which Heilbrunn finds to be particularly troublesome and which he defines as the “belief that the state and society are coterminous with religion.”

Coterminous? As in having a common boundary? As in being coextensive with, as though the state, society, and religion are essentially one and the same? And since integralism has been mainly associated with Catholicism, does Heilbrunn mean to suggest that one day, perhaps one day all too soon, a conservative populist president-elect might be taking a page from JFK and sending that one-word telegram to the Pope: “Pack”—and, more than that, actually mean it?

Apparently, Jacob Heilbrunn is very worried about such a prospect. By the same token, he is completely unworried about pretty much everything that worries a conservative populist, whether that be the deep (or administrative) state, expertise run amok, various versions of internationalism run amok, COVID restrictions run amok, a borderless country, and/or various secular religions replacing real religion.

On the last score, the worry of conservative populists (otherwise defined by Heilbrunn as the “new authoritarians”) is similar to that of John Adams, who doubted that a republic was genuinely fit for anything other than a religious people. Therefore, Adams also worried about what might happen to this republic if the American people and their leaders ceased to be religious. In sum, Adams would likely be very worried today. But would he be an integralist? Or a conservative populist? Or a “new authoritarian”? Who knows? However, this is certain: John Adams did not want a state religion then, and conservative populists do not want a state religion today.

Ironically, the Catholic integralists and the Calvinist John Adams have more in common with one another than any of them have with Jacob Heilbrunn, who waits until the very last page of this book to confirm his belief in something about which, at best, the contents of the book have left serious room for doubt.

That something is this: His rightist romantics have sought to make “common cause” with foreign dictators in order to “champion illiberal democracy” right here at home. Therefore, “now as in the past, one thing remains consistent in the long and melancholy saga of the American Right’s self-abasement before tyrants. It puts the American people, American ideals, and American independence last, not first.” And on that happy note, the book ends—but this review does not.

It probably could go without stating, but Heilbrunn does not confine himself to quarreling with fellow scribblers on the right. All along the way, his ultimate goal is his attempt to explain how we got to where we are today regarding the greater political scheme of things.

And “today,” for this reviewer, is December 2024, or a mere handful of days before the return to the White House of one Donald J. Trump. Heilbrunn also holds off until right near the end of this book to bother mentioning the individual who undoubtedly stands as the right’s most dangerous romancer-in-chief in the narrowed eyes of one Jacob Heilbrunn and those who share his worries.

On the one hand, Heilbrunn wants his readers to believe that Trump is a committed and, yes, dangerous “champion of illiberal democracy,” whatever that exactly is. On the other hand, Trump is simply the latest manifestation of a long-standing disease. After all, in “lavishing praise on Putin and other dictators . . . Trump wasn’t creating a new style of right-wing politics. Instead, he was building on a long-standing tradition.”

But what exactly is that long-standing tradition? Heilbrunn begins his story with the American entry into the Great War and with Americans bent on “courting Kaiser Wilhelm.” Trouble for Heilbrunn begins almost immediately, since opposition to American entry into that war came from both the right and the left. Therefore, at least to some extent, both left and right could be charged with courtship of, if something less than out-and-out romance with, the Kaiser.

Heilbrunn, of course, then turns to Americans who romanced both Mussolini and Hitler. And once again, the same problem emerges, since there were those on the left who were enamored of Mussolini, the former socialist, as well as those on the left who did not object to German “national socialism” in the mid-thirties and/or who didn’t favor going to war in the late 1930s. Could they then be accused of “courting” Hitler or Tojo as well?

Entire chapters are then devoted to such presumably pre-Trumpian figures as Charles Lindbergh, Joe McCarthy, William F. Buckley, Jeane Kirkpatrick, and Pat Buchanan. To be sure, many other figures factor into each chapter as well. More often than not, they turn out to be former leftists, even one-time communist sympathizers, whether of a Stalinist or Trotskyite bent. Freda Utley and James Burnham are prime examples. But instead of crediting them with coming to terms with Soviet totalitarianism, they are criticized by Heilbrunn for their starry-eyed attachment to right-wing authoritarianism.

Were she still with us, Jeane Kirkpatrick might well be surprised to find herself in the company to which she has been assigned here. But Heilbrunn is nothing if not insistent on fitting her into his larger scheme. The author of “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” the Commentary magazine essay that would later catapult her into the Reagan administration, this soon-to-be former Democrat was finally able to “unleash her inner conservative.” More than that, her “fervor for all things authoritarian exceeded even that of her (Reagan administration) colleagues.”

Yes, “fervor” it is, at least according to Jacob Heilbrunn. It wasn’t that Kirkpatrick, the Georgetown academic, sought to explain a few key differences between totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. It wasn’t even that she was offering a straightforward defense of the latter (which she wasn’t). Nor was it simply a matter of her preference for the latter over the former. Given her inner romantic, there had to be a “fervor” about it all, yes, a “fervor for all things authoritarian.”

Of course, Heilbrunn cannot resist taking a victory lap at the end of the Kirkpatrick chapter by noting that she turned out to be wrong about her claim that the key difference between a totalitarian regime and an authoritarian regime was not simply the total control of the former, but the permanence of its rule. Of course, your reviewer cannot resist noting that Heilbrunn gives no credit to either Kirkpatrick or the Reagan administration for having had anything to do with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

That collapse eventually brings us to the likely reason that Jacob Heilbrunn decided to write this book, as well as to the likely reason that he found a publisher. In other words, that collapse finally brings his story to the ultimate romance between Donald Trump, romantic lapdog, and Vladimir Putin, the alleged object of Trump’s slobbering affections.

Geopolitics is apparently beside the point for both Heilbrunn and Heilbrunn’s version of Trump. Heilbrunn wants to believe that the real goal, nay the ultimate goal, of Trumpism, past and present, is the “dismantling of American democracy.” And he wants his readers to believe that Trump’s complaints about NATO have nothing to do with foreign policy. Instead, they are “rooted in real admiration for Putin,” specifically for his “disdain for LGBTQ rights, for his support for the Russian Orthodox Church, and for his cult of masculinity.”

Therefore, President Trump was willing to “sabotage” NATO in the name of accommodating Putin. But was it really an act of sabotage to challenge European members of NATO to honor their financial commitments to the treaty? If so, were the past failures of those countries to pay their fair share a collective act of sabotage all its own? Or was the Biden administration’s cutback on American energy production, thereby making Germany more dependent on Russian supplies, a comparable act of sabotage? Not according to Jacob Heilbrunn. It’s only Trump who is a saboteur.

If author Heilbrunn might be excused for having difficulty sorting out the true motives of the key players, maybe Donald Trump should be excused as well. After all, if he stands charged with being little more than the culmination of a century-long story of misguided romance with right-wing dictators, just who is it who has led him astray? Or has each of the historical figures under discussion in this book somehow made his or her unique contribution to creating Trumpism? And if so, would it really have been possible for Donald Trump or anyone else to sort things out, assuming, of course, that Trump had been paying attention to his predecessors among Heilbrunn’s long list of rightist romantics scattered throughout history?

One such figure has been left unmentioned until now. But he, too, is the subject of an entire chapter. Its title gives this little game away: “Menckenized History.” That figure, of course, would be none other than the Baltimore curmudgeon H. L. Mencken. So let’s see, this process of cozying up to rightist dictators began with the romantic inclinations of a libertarian-minded, agnostic, skeptic/cynic, humorist/wordsmith (Mencken) and concludes with the equally romantic desires of a set of strongly believing Catholic integralists. Whether as a builder, a TV host, or a president, it’s not likely that Donald Trump has ever had to deal with as disparate a group as these alleged America Firsters—or should that be the renamed and recast America Lasters?–who came before him. It’s also not very likely that he would ever have paid much attention to their doings or writings.

And Jacob Heilbrunn? He remains intent on shepherding all of his romantics into one monolithic herd. The problem is that they really don’t all belong in the same herd. But they all can be linked in a different way. Few, if any, of them have been treated fairly by Heilbrunn, given that his operating presumption throughout the book is that the underlying goal of his subjects has been the subversion of democracy here at home.

Henry Louis Mencken couldn’t possibly have been bothered. The practice of democracy in America gave him too much to write about as it was. Besides, it was always doing its best to subvert itself.

Mencken once defined democracy as that theory of government that holds that the common people know what they want and deserve to get it good and hard. Were the libertarian-minded Mencken with us today, would he think that his definition of the actual workings of democracy would apply more to those on the left who claim to be saving democracy or to those on the right whom Jacob Heilbrunn claims are bent on its subversion? To ask this question is to answer it.

To be sure, H. L. Mencken was no fan of democracy, aside from its entertainment value. But he was also no conservative populist. Like a reborn Jeane Kirkpatrick, he would be surprised to find himself included on Jacob Heilbrunn’s roster of rightist romantics. More than that, he would be stunned to be regarded as a precursor to Donald Trump.

Undeterred, Heilbrunn features Mencken prominently among his carefully selected rightist romantics. In doing so, he takes after Mencken, a descendant of German immigrants, for being little more than a romantic fool when it came to both the Kaiser and Hitler. If only Heilbrunn had been content to have been as off-handedly dismissive of the rest of his rightist romantics. Then again, had he done so, he might not have had a book to write. Then again, that might not have been such a bad thing. Either way, meaning this book or no book, reading or re-reading Paul Hollander’s unromantic account of his “political pilgrims” would be a better investment of time and money.

John C. “Chuck” Chalberg has performed as H. L. Mencken. He writes from Bloomington, MN.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!