by Chris Nashawaty.

Flatiron books, 2018.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $27.

Reviewed by Mark Judge

When I was in college in the 1980s in I worked at a movie theater in Maryland, the Bethesda Cinema ’n’ Drafthouse. The Drafthouse had begun as the Boro, a beautiful art deco movie space designed in 1938 by “Dean of American Theatre Architects” John Eberson. The Boro became the Bethesda Theater in 1939, and in the early eighties the Bethesda transformed into the Cinema ’n’ Drafthouse, its interior reconfigured with a round tables and a kitchen that served pub food. It was a precursor to today’s Alamo Drafthouse.

It was while bartending at the Drafthouse that I developed a solid criterion for judging a comedy scene. If the kitchen staff left their posts to watch a scene, it was funny. Bill Murray, playing a masochist going to sadistic dentist Steve Martin in Little Shop of Horrors would empty the kitchen. So would the Randall Tex Cobb intro in Raising Arizona. The all-time king was probably the Sam Kinison freak-out at the brainwashed liberal student in Back to School. Pizza and nacho orders would back up for ten minutes when Kinison came on the screen, the cooks all standing along the back wall guffawing.

A film that was popular back then, but never was adored among the knowledgeable staff as ardently as these other films, was Caddyshack, a 1980 comedy starring Bill Murray. Caddyshack, despite the memories of the middle-aged men who remain its fans, is a bad movie that has not aged well. The film is a slobs-vs-snobs story set at a Florida country club. The drug references, too-broad slapstick, juvenile poop jokes, and characters like Murray’s mentally challenged groundskeeper Carl Spackler have become pop culture touchstones. Yet films of the same era that emptied the kitchen at the Drafthouse—films like Raising Arizona, Back to School, Beverly Hills Cop, The Princess Bride, and Little Shop of Horrors—not to mention Tootsie, arguably the best comedy of the 80s—were and remain funny in sharp and delightful ways that Caddyshack is not.

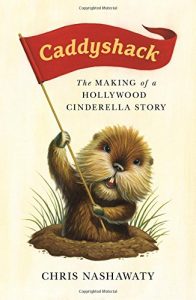

Caddyshack is the subject of a beautifully written and even historically important book. Caddyshack: The Making of a Hollywood Cinderella Story by Entertainment Weekly writer Chris Nashawaty, is about the making of Caddyshack, but also about how American comedy was changed by the counterculture in the 1960s and 70s. Caddyshack was the product of a cultural revolution in American comedy, albeit a revolution that thankfully did not completely destroy classic comedy forms as they existed before the 1960s.

Caddyshack was the fruit of three different influences: National Lampoon magazine, the Second City comedy troupe in Chicago, and the TV show Saturday Night Live.

In 1966, the magazine the Harvard Lampoon gained national attention when it produced a parody of Playboy magazine. The minds behind the spoof were Lampoon editors Doug Kenney and Henry Beard, two men who are at the heart of the Caddyshack story. Great-grandson of James Buchanan’s vice president John C. Breckinridge, Beard grew up at the Westbury Hotel in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Beard was, in Nashawaty’s phrase, “the genuine WASP article.” Kenney was from a working class neighborhood Chagrin Falls, in Ohio. A “hard-to-pin-down wild card,” Kenney was eccentric, brilliant, and able to put his entire fist in his mouth. One movie producer compared Kenney’s spontaneous comic mind to a genius playing jazz.

Kenny and Beard transformed the Lampoon from “a sort of patrician social club of high IQ gentlemen smart-asses biding their time before they graduated and headed off to Wall Street or to join the family law firm” to a nationally recognized cutting edge of American comedy. This cultural revolution in a sleepy comedy mag coincided with a larger cultural shift. Nashawaty: “When [Kenney] entered Harvard in 1964, grass was a taboo recreational punishable by a steep jail sentence. Just a few years later, you couldn’t walk down Massachusetts Avenue without getting a contact high.”

Following the Playboy hit, Penney and Beard parodied Life magazine and The Lord of the Rings, then purchased the rights to the Lampoon name and created a national magazine, National Lampoon, which launched in 1970. They did a hugely popular high school yearbook parody, a radio program, and The Lemmings, a satire of Woodstock. To stage The Lemmings the Lampoon drew talent from Second City, a popular Chicago comedy troupe. The Lampoon discovered Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd, Bill Murray and Brian Doyle-Murray, Tony Hendra, Gilda Radner, and Christopher Guest. “Kenney and Beard quickly create a multimedia empire in print, radio, and on stage,” Nashawaty observes. Around that time a new countercultural comedy show, Saturday Night Live, launched. Its young producer Lorne Michael staffed the first seasons with new young talent from Second City. (It should be said that, at least in my view, a titanic influence on the new comedy was Mad magazine, which never gets enough credit.)

It was a perfect storm of talent and the times. The high point came with the 1978 film National Lampoon’s Animal House. Made for $3 million and written by Kenney, Harold Ramis, and Chris Miller, the film exploded, taking in over $140 million. At the same time Saturday Night Live had become a hit. Nashawaty: “A generational fault line had opened up and swallowed yesterday’s style of comedy. Soon Steve Martin, Cheech and Chong, and Lorne Michaels’s 30 Rock stable of cracked comic minds would replace them with their stoned observations, barbed satire, and absurd meta-shtick. Big screen comedy was now a young person’s game.”

Like many other cultural critics, Nashawaty might exaggerate how revolutionary the new comedy was. Yes, Chevy Chase’s smirk, Steve Martin’s meta-comedy (comedy that comments on comedy), and Bill Murray’s winking takes on show biz hip and cheesy lounge singers were a long way from Leave it to Beaver. Yet many SNL skits could have appeared in earlier eras. Chase did pratfalls, the most ancient form of comedy. Gilda Radner character Roseanne Roseannadanna was based on a woman with no social graces, not an avant-garde concept. The star of Caddyshack was not a Second City or SNL member, but Rodney Dangerfield, who was not exactly a hippy or an arch ivy leaguer sneering at Middle America (although as Nashawaty notes, Dangerfield did smoke huge amount of pot during the shoot). The climactic chaos in the parade-breaks-down scenes of Animal House are right out of Chaplin. What was new in the new comedy was the irony and the politics, as well as the sexual openness, drug references, and the “gross out” humor.

Furthermore, the anarchic nature of the new comedy would quickly lose direction if it wasn’t guided by a strong directorial hand. When Universal bought the script to Animal House a bright young director, John Landis, was brought in to direct. Landis was at first resented by many cast members, and he instantly saw problems with the script and casting. The structure that Landis placed on Animal House (not least of which was insisting that there be a good fraternity and a bad one in the story, not just the cutups at Delta Tau Chi) made the film more coherent.

Harold Ramis, the director of Caddyshack, exerted no such control. The Caddyshack script, written by Ramis, Kenney, and Brian Doyle-Murray, was rewritten so often that they ran out of colors to note that a revision had been done. The “guided improvisation” led to scenes that fell flat, like the one where Bill Murray’s groundskeeper Carl Spackler meets upper-class golf pro Ty Webb. Characters were written out of the story at the last minute. The ending relies on the most tired of Hollywood tropes, a big explosion. The heavy drug use by the cast hampered the performances. Compared to a brilliant 1980s comedy like Tootsie, Caddyshack views like a home movie.

Caddyshack was widely panned at the time of its release in the summer of 1980. (Meatballs and Stripes, the two films that Bill Murray starred in before and after Caddyshack, remain superior efforts; his 1993 comedy Groundhog Day is a masterpiece.) The bad reviews made Kenney become deeply depressed, and at a promotional press conference—a scene that opens Nashawaty’s book—Kenney, by then a drug addict, verbally abused reporters and had to be helped out of the room by friends and family. Kenney died on August 27, 1980, aged 33, after falling from a 35-foot cliff in Hawaii. His death was classified as accidental by Kauai police.

Mark Judge is a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C.