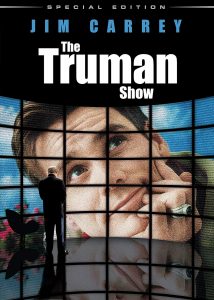

Written by Andrew Niccol.

Directed by Peter Weir.

Paramount, 1998.

Reviewed by Titus Techera

On its twentieth anniversary, The Truman Show turns out to have been prophetic about what happens to us when we go digital. In the terms of the old world of television, it tells the story of total surveillance and total artificiality as conditions of normal American life. It’s not totalitarian tyranny—nor a scientific ideology trying to transform being human—it’s reality TV we can believe in. The deepest teaching of the story is that we should fear not oppression or conspiracy but the abuse to which we will consent.

Surveillance in the movie is not the hypermodern, tech-based deep state intruding in your private life. It’s actually reactionary and comes about as a result of commercial imperatives—we end up consuming everyday life in a nostalgic mood, looking for a childhood paradise, for safety, and for escape from endless change, innovation, and insecurity.

America is playing peeping tom on the largest imaginable scale with Truman, but completely without kink. There’s no sex and no one wants to see him naked. America is idealistically in search of the ultimate everyman, someone exactly like us, but somehow lovable and worth elevating above the rest of us, like an idol. We should notice that the world of social media endlessly reproduces this pattern, where we seek yet one more Truman, one last thing to make us feel human—one more cute animal, one unexpected moment of grace, one person breaking down and crying, whether in gratitude or despair. Something real, something to connect us to the world and other people.

Truman himself, played by Jim Carrey at the top of his powers and the height of his rebellion from Hollywood celebrity, is perfect for the role a desperate society has conceived for him. He is an innocent, the last natural man in America. Free of suspicion, Truman has no idea that his life is a show to everyone else—that all his secrets, all his moments of spontaneity are consumed by an eager audience. Much like our teenagers, as much digital ghosts as human beings, Truman has no idea that stealing his self-awareness is the price America is willing to pay in order to cling to normality.

Truman, both actor and anti-actor, is the end of a long process that started in movies with the fall of the Hollywood stars. The blessed few, who ranked above us, gradually came down into our lives. Indeed, by their very power to mesmerize on the big screen, they created a fictional America we, too, could be part of—we ended up believing the characters were real people at some level—that’s why we react to famous actors the way we do. As Walker Percy noted in The Moviegoer, we’re half-convinced that fake movie characters are more real than real people.

The stars then were reduced to famous characters and eventually the prestigious Hollywood movies were reduced to B-movies: franchises and sequels. Everything ended up on TV, where actors play versions of themselves we’re going to find attractive, witty, and, every once in a while, insane in an interesting way. In all these ways, the audience took possession of fiction and made it walk the earth just like the rest of us. The fantastic was normalized to the point of becoming regular and banal. Faced with the drudgery of our lives and the insatiable demand for more of the same, heroism turned to sarcastic neurosis. Character was liberated from plot or story and characters with no real story, no beginning or end, began to dominate our fantasies. We’re all stars now, or trying to be, and judge our experience under a jurisprudence of superlatives.

At the same time, of course, characters began inhabiting a fake world that continuously advertises corporate consumption. Truman is trapped in reality TV, which is a combination of soap opera and paparazzi invasion of privacy, and in continuous advertising—his very life is being advertised and it’s full of corporate products for viewers to buy, since they buy into his world, since they buy into his character. He is a brand ambassador without realizing it. He can look perfectly authentic only because his life is fully fake. This will happen increasingly in our future. Celebrity is now advertising and storified fake lives will be the ritual space of advertising.

Of course, we should also talk money. In America, we hope, at the best of times, we’ll do good by doing well or vice versa. But we cannot publicly entertain the thought of sacrifice—it’s indecent! It’s too demanding! We know we don’t have anything except what we acquire, and we’re always on the clock because we’re always behind the times. It’s hard to say whether we ever have enough; it’s certain there’s always so much more to have. The fantasy of Truman is that he doesn’t have to worry about money—his life is safe, and so is his livelihood. The truth about Truman is that he’s the last slave in America, bought and paid for by a corporation.

Truman, of course, gradually learns to break out of his perfect suburban-by-the-seaside life, and goes off looking for love. But in the real world of 2018, we’re all Truman—or runners-up for the job. Since we cannot yet think of digital technology as anything better than TV celebrity—see social media—we are now reproducing endlessly the exploitation of other people to satisfy our cruelty and sentimentality, and double that with the self-exploitation of putting on The Truman Show for everyone else, just in case we can attract enough attention to maybe get to something better than we have. As soon as Truman jumped out of his predestined role, we jumped into it.

And because we’re all Truman, no one can see it. If you look at journalists on Twitter, you will see The Truman Show. They mix their work with their personal lives in one continuous stream, as though public and private were not different after all—they’re putting on the show of authenticity, revealing all of themselves, although at all times they impersonate characters that they hope will make them more popular. It works because they believe it themselves—with every detail they expose, every hangup, every comic failure or lapse, they are humanized, as we used to say about characters in stories …

Such people, of course, are not fit to warn America about the state spying on all of us—they could never stand up for us against the few tech corporations that exploit us all, either. And how about us? We’re worldly wise: we already know there’s nothing we won’t publicize about ourselves, however shameful, especially if it’s scandalous, in the hope of attracting attention. That’s what YouTube is for, the epic as much as the fails—and above all the epic fails, where self-abasement creates popularity! In our self-abasement, in the continuous confession of our worthlessness that is social media, we cannot find the moral resources for outrage at how the state invades our lives. If only! That would be a sign we’re worth the attention! As much as we loathe ourselves and our world, so much do we hope that a leap into digital technology will be lovely and finally we’ll find love in the clouds.

Revealing ourselves is a rather desperate attempt to prove uniqueness. We don’t see how obscene we are, for that reason. We couldn’t find the resources of psychological complexity and self-awareness to feel ashamed of our shamelessness. It’s not that the Truman character is a man of virtue and we are vicious—the difference is, he has the pride that leads him to escape surveillance. Mostly, we don’t, because we know too, too well that we’re all the same.

Truman actually believed he was special—however oppressive normality got, there were things gnawing at him, through barely recollected images of a fake past, suggestions that real life is somewhere else and beckoning to him. We proclaim specialness endlessly, in agony, but we don’t believe it. What we believe is, we’re unique. We know it to be true because of our heart-rending anonymity. Nobody cares—we’re alone—that’s solid proof we’re individuals—and it’s almost unbearable.

The judges of the digital world are more ruthless than the state or even the corporations—they judge us by analytics and statistics: do we even register, in the great eye of democracy, which is open to everything in the world? The great eye never looks upon us, really—we’re just helping others get marginally more attention than they already have, which is more on any given day than what we can get in a lifetime. Since our journalists are no better than us, they cannot even ask themselves what they’re participating in or what it might mean to give people an alternative to the cycle of self-exploitation and surveillance. Who’s left to tell the truth about what we’re doing to ourselves?

The Truman Show brought together the elements of social construction of reality in order to examine what history might do to us. Can we take control of our society in some way and shape it by our values? The combination of reality TV, corporate consumerism, a fake paradise to live in, and the equation of the banal with the important describes our democratic taste. What if we were offered everything we thought we wanted? Apparently, we’re all extras on The Truman Show, mugging for the camera as best we can while sleepwalking Trumans do what celebrities do, which is sacrifice themselves for us.

Director Peter Weir and writer Andrew Niccol did a great job of dramatizing this first stage of the digital future and we owe them a debt of gratitude, not least for making such a terrible lesson to learn such a pleasurable story to watch. Of course, this is increasingly our source of real experience—as our lives become too abstract and digital, we will find reality in the less abstract medium of cinema. Next, we’ll have to figure out how to deal with this situation, where we feel increasingly lonely and ineffectual, divided by technology, and increasingly interchangeable as we revere the same things that capture all the attention. Since we have imitated Truman so far, we might as well learn from him to escape surveillance by love. That, at any rate, is the advice of Andrew Niccol’s latest movie, Anon, where total surveillance is the creature of the state and tech corporations.

Titus Techera hosts the American Cinema Foundation podcasts and is a contributor to The Federalist, National Review Online, Catholic World Report, and the University Bookman. He tweets as @titusfilm.