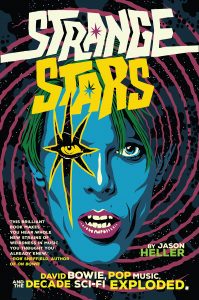

by Jason Heller.

Melville House, 2018.

Hardcover, 272 pages, $27.

Reviewed by Mark Judge

In 1980, musician David Bowie released a new album, Scary Monsters. On the record was a song called “Ashes to Ashes,” which was an update of “Space Oddity,” a song Bowie had first recorded in 1969. “Space Oddity” had been inspired by Bowie’s multiple viewings of Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 science fiction masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey. The song recounted the adventure of Major Tom, an astronaut sent into space. Thrilling in its poetic and mystical imagery, the song celebrated America’s Apollo 11 mission, which would launch on July 16, 1969, five days after Bowie’s single was released.

Little more than a decade later, and after creating the persona of an alien named Ziggy Stardust and starring in the science fiction film The Man Who Fell to Earth, Bowie revisited Major Tom in “Ashes to Ashes.” Now, however, Major Tom was described as a junkie drifting in space without purpose or direction.

What happened between “Space Oddity” and “Ashes to Ashes” is the subject of a interesting new book, Strange Stars: How Science Fiction and Fantasy Transformed Popular Music by Jason Heller. The book covers the intersection between rock and roll and science fiction in the 1970s, a connection that was deep, widespread, and produced both kitsch and great art. In the 1970s popular musicians from Bowie, Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic, and Blue Oyster Cult to more obscure acts like Klaatu, Kraftwerk, and X-Ray Spex capaciously explored such science fiction themes as interplanetary exploration, androids, time travel, the future, and the nature of human consciousness. The influences ranged from George Orwell and Kurt Vonnegut to Anne McCaffrey, Tolkien, the libertarian Robert Heinlein—whose 1953 book Starman Jones mesmerized a young Bowie—and the hippy British author Michael Moorcock.

While Bowie is the anchor of Strange Stars, Heller has cast his tractor beam quite wide. He touches on virtually every band or musician from the Me Decade who was devoted to or dabbled in sci-fi. This is both a strength and a weakness of the book. Heller’s digging reveals some great factoids. It’s refreshing that he notes that long before 1977 and Star Wars, pop artists were consuming sci-fi literature and transferring the themes and stories into their music. Jimi Hendrix claimed to have seen a UFO as a kid in Seattle in the 1950s, and voraciously devoured science fiction books like George Stewart’s Earth Abides and Philip Jose Farmer’s Night of Light, which gave Hendrix the phrase “purple haze.” As early as 1968, Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner was riffing off John Wyndham’s novel The Chrysalids in the song “Crown of Creation.” And who knew that a young George Lucas was filming Altamont, the 1969 Rolling Stones concert in California that ended in disaster? German techno-rock pioneers Kraftwerk are here, as is George Clinton’s ever-shifting account of the time he and musician Bootsie Collins saw a UFO up close. There’s also jazz experimentalist Sun Ra, performers of Afrofuturism, which commingled sci-fi and the story of the African diaspora. Also touched on: Queen’s use of legendary science fiction artist Frank Kelly Freas’s 1953 Astounding Science Fiction cover illustration for their 1979 album News of the World; William Burroughs’s A Clockwork Orange; Doctor Who; H. G. Wells; The Six Million Dollar Man; reggae sci-fi; and Paul McCartney’s album Venus and Mars. And so on.

If you’re a science fiction and fantasy fan, this stuff is wonderful. (Strange Stars even reminded me that ELO—my favorite pop band when I was a kid in the 1970s—used a lot of space imagery.) Yet there is a lot of information here, perhaps a bit too much. Like William Gibson’s Johnny Mnemonic, readers might wish they had an extra hard drive in their souls to contain it all.

Strange Stars has a nice ending that hints that science fiction taps into something deep in the human soul, and is more than just a fad or reflection of a particular culture. In 1980, in an interview for the release of Scary Monsters, David Bowie—the only musician ever inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame—said this:

When I originally wrote about Major Tom, I was a very pragmatic and self-opinionated lad that thought he knew all about that great American dream and where it started and where it should stop. Here we had the great blast of American technological know-how shoving this guy into space, but once he gets there he’s not sure why he’s there. And that’s where I left him. Now we’ve found out that he’s under some kind of realization that the whole process that got him up there has decayed, was born out of decay; it has decayed him, and he’s in the process of decaying. But he wishes to return to the nice, round womb, the Earth, from whence he started.

Even as Bowie approached death from cancer in 2016, he looked to the stars. The title track of Bowie’s final album, Blackstar, features a video with a figure in a NASA-style space suit. Behind the visor is revealed, as Heller observes, “a skull encrusted with jewels and gold filigree—the ornamented corpse of a space traveler left to spin through eternity.”

Mark Judge is a writer and filmmaker in Washington, D.C.