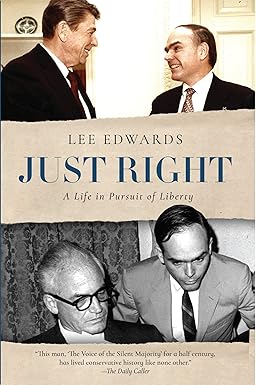

By Lee Edwards.

ISI Books, 2017.

Hardcover, 378 pages, $29.95.

Reviewed by George H. Nash.

In his lively new memoir Just Right, Lee Edwards remarks that four distinct groups have molded the modern American conservative movement: “philosophers” like Friedrich Hayek and Russell Kirk; “popularizers” and “men of interpretation” like William F. Buckley Jr.; “politicians” like Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan; and “philanthropists” like Henry Salvatori and Richard Scaife. To these categories we might add two more: organizers who create institutions and channel the enthusiasm of citizens at the grassroots, and historians who help all the groups develop self-awareness and a sense of the enduring significance of their labors.

It is in these latter roles—as activist-organizer and historian—that Edwards has worked with distinction in a career that has now lasted nearly sixty years. His has been, he tells us, “a life in pursuit of liberty,” a life that led to his being “present at nearly every major event of the modern conservative movement.” In Just Right he tells his story with candor, perspicacity, and verve.

Lee Edwards was a “cradle conservative” who grew up in an ardently anticommunist home in the suburbs of Washington, DC. His father, a veteran political reporter at the Washington office of the conservative Chicago Tribune, covered Congressional investigations of Communist espionage and was a close friend of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who often visited the Edwards home. But it was not until 1956 that Lee, living in Paris as a student and aspiring novelist after a stint in the US Army, experienced a shock that determined the direction of his life. Outraged by the Soviet Union’s brutal suppression of the Hungarian Revolution against a communist dictatorship that autumn, and by the U.S. government’s failure to respond, Edwards (he tells us) “took an oath. I resolved that for the rest of my life, wherever I was, whatever I was, I would help those who resisted communism however I could.”

Edwards’s commitment to anticommunist conservatism began in earnest in 1958, when he published his first article in National Review. Not long thereafter, while still in his mid-twenties, he became press secretary to a conservative U.S. senator from Maryland, a position he held for several years. Active in the DC Young Republicans, in 1960 he participated in the founding of Young Americans for Freedom (at William F. Buckley Jr.’s home in Connecticut) and became the founding editor of its crusading monthly, New Guard. In the early 1960s, YAF (the first great youth movement of the decade) grew exponentially as Edwards and other YAFers staged audacious rallies in Madison Square Garden and elsewhere and embraced an emerging conservative superstar, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

Edwards devotes nearly one-third of his memoir to a riveting insider’s account of Goldwater’s campaign for President in 1964. In 1963 the young public relations maestro was appointed news director of the National Draft Goldwater Committee, from which position he dealt with the press, wrote most of the committee’s literature, supervised the production of campaign commercials, and oversaw “the most sophisticated mass communications system ever put together for a national political convention.” In the ensuing Fall campaign, he served as deputy director of information for the official Goldwater organization and worked to the brink of exhaustion for his hero’s election.

Edwards pulls no punches in his first-hand account of the doomed Goldwater campaign, which a friend described as a “glorious disaster.” He notes Goldwater’s “inspiring and infuriating” contradictions, the myopia and haughtiness of some in his inner circle, and the vicious and wounding smears that political enemies heaped upon the conservative senator. In pages that may astonish some readers, Edwards documents President Lyndon Johnson’s egregious misuse of the FBI and CIA to infiltrate Goldwater’s campaign organization. Johnson, running as the incumbent against Goldwater, ordered the CIA to place a spy in Goldwater’s headquarters. The spy supplied the White House with advance copies of Goldwater’s schedule and speeches, thus enabling the Democrats to prepare rebuttals even before Goldwater spoke. Johnson also (says Edwards, citing sources) ordered the FBI to search its files (presumably for dirt) on Goldwater’s fifteen senatorial aides and even ordered the FBI to bug Goldwater’s campaign plane. Unlike Goldwater, who took the high road in his stubbornly idiosyncratic and sometimes self-defeating way, LBJ (“a modern-day Machiavelli”) was evidently determined to win, and win big, at whatever cost.

Nevertheless, Edwards contends that despite the debacle that conservatives suffered in 1964, Barry Goldwater was “the most consequential loser” in American political history. By means of his candidacy, a vibrant political movement called conservatism coalesced—and did not die. Goldwater’s seemingly quixotic and disastrous crusade helped the Republican Party become truly national and paved the way for the eventual triumph of Ronald Reagan.

For Edwards himself the Goldwater campaign was also transformative. Until 1964, he writes, he had been “just another promising, young conservative writer and political activist,” “stuck in the minor leagues.” After the election, and with a well-earned reputation as a “creative publicist,” he would “play in the majors.”

In 1965 Edwards established his own public relations firm in the nation’s capital. For the next two decades he served as “a publicist, coordinator, and fundraiser for nearly every organization on the right.” Gifted with superabundant energy, organizational acumen, and the ability to write speedily and clearly, as well as a principled commitment to the conservative cause, he found himself in demand as a consultant and ghostwriter. He began to write books of his own, including the first political biography of Ronald Reagan (in 1967) and a political handbook for conservatives a year later. In 1975 he agreed to become the founding editor of the monthly Conservative Digest, a mass circulation magazine for the populistic New Right (a precursor of the Tea Party movement). For a time he was a syndicated columnist.

And all the while, he did not forget his fervent, anticommunist vow of 1956. Indeed, organized anticommunism was at the forefront of his tireless activism in the 1970s. Through such organizations as the American Council for World Freedom (which he founded in 1970) and the National Captive Nations Committee (which he served as executive director for almost ten years) he kept the anticommunist banner unfurled, via an endless torrent of conferences, rallies, policy papers, and other publicity. After orchestrating a massive, pro-Vietnam War rally in Washington in 1969, he was profiled in the New York Times the next day as “The Voice of ‘the Silent Majority.’”

By the early 1980s, though, the frenetic, “roller coaster” life of the publicist-activist was losing its appeal. Married now, with two young daughters, and on the cusp of middle age, Edwards felt the need for “a more measured life.” With his wife’s support he took a radical step: forsaking his career in public relations, he entered graduate school. In 1986, at the age of fifty-three, he received a Ph.D. in World Politics from the Catholic University of America.

Although Edwards continued to practice political journalism in Washington for a number of years thereafter, his energies turned increasingly to a new vocation: becoming a historian of American conservatism. Since 1990 he has published a cascade of more than twenty illuminating volumes on this subject, including biographies of Walter Judd, Barry Goldwater, Edwin Feulner, and Edwin Meese; histories of the Heritage Foundation and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute; and a history titled The Conservative Revolution: The Movement that Remade America. His brief, incisive biographies The Essential Ronald Reagan (2005) and William F. Buckley Jr.: The Maker of a Movement (2010) are masterpieces of the genre.

It is a mark of Edwards’s commitment to his second calling as a historian that in 2002, at the age of sixty-nine, he became a full-time Senior Fellow of the Heritage Foundation—and promptly embarked on “the most productive years of my life.” Nearly sixteen years later, he is still there—and still writing.

All this and more is covered in the engaging pages of Just Right, which will no doubt serve future historians as a valuable primary source. But there is one project that this indefatigable activist-turned-historian has not completed, as he recounts in the final chapters of his book. In 1990, inspired by a suggestion from his wife, Edwards resolved to establish in Washington a memorial to the victims of communism—more than 100,000,000 of them—who have died unnatural deaths at communist hands around the world since the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

Since the early 1990s Edwards has selflessly dedicated himself to this mission, for which he feels his entire life has been “a preparation.” As cofounder and longtime leader of the Victims of Communisms Memorial Foundation, he has found his path strewn with obstacles. There have been successes—notably the establishment in 2007 of the Victims of Communism Memorial, dedicated in a park in downtown Washington by President George W. Bush. Meanwhile the VOC Memorial Foundation has developed educational tools and an excellent website and has become in Edwards’s words, “the primary disseminator of information about communism” and its hideous record.

But one step—the climactic one—has yet to be taken in fulfillment of Edwards’s dream: the establishment of a major, international museum of communism near the National Mall in the nation’s capital. Perhaps the publication of Just Right will generate the necessary momentum for success in this worthy endeavor.

Edwards concludes his memoir on a confident note. Although conceding that “the future of conservatism remains difficult to discern,” he nevertheless contends that “conservatives have every reason to be optimistic.” The conservatives, he assures us, “will prevail,” sustained by “the power of their ideas—linked by the priceless principle of ordered liberty.” Conservatives, he insists, are “well positioned” to overcome the challenges ahead.

In 2017, amidst the tumult of the Trump presidency and the fissures and strife abounding on the Right, some conservatives may find it hard to share Edwards’s optimism. But surely they can profit by his example and by the inspiring story that he tells. For six decades—longer than any American conservative activist now living—he has labored without stint for the cause, as his memoir so splendidly attests. If anyone has earned the right to counsel perseverance, it is he. In Just Right he shows us how he did it—and why those who share his political faith must resolve, like him, to carry on.

George H. Nash is author of The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 and Reappraising the Right: The Past and Future of American Conservatism. He is a Senior Fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal.