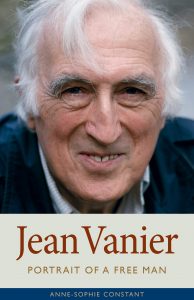

by Anne-Sophie Constant.

Plough, 2019.

Paperback, 250 pages, $18.

Reviewed by Matthew Loftus

About a decade ago came a minor skirmish in the ongoing fight among evangelicals about our disposition towards the faith that goes back perhaps as far as the Reformation, one that has interesting parallels towards current debates about our postliberal future. On one side were the more “radical,” such as David Platt (who wrote an eponymous book on the subject) and Shane Claiborne (whose book was probably just as influential and kickstarted the New Monasticism movement). On the other side came folks like Anthony Bradley and Matthew Lee Anderson, who wanted a quieter, more humdrum faith that might burn fewer people out. The two sides, it seemed, disagree not only about how much “radical” rhetoric was necessary to describe a life of Christian faithfulness, but also how radically such a life of faithfulness would diverge from the median life course of Christians in the West.

It is hard to tell, but it seems the radicals won: last week I spoke to a church where maybe one or two of the adults were under fifty across two services and yet there was, at the beginning of the service, a video that could have preceded a professional wrestling match but for its subject: a church committed to authenticity and sharing the Gospel. Words slammed into the screen behind a shadowed cross, the narrator spoke with an urgency like a military recruiter. Christian conferences, as least the ones I still attend, still traffic in tropes of radicalism and repeat urban legends about early Moravian missionaries selling themselves into slavery so they could carry the gospel to the New World. When the contrast is drawn between the materialistic life focused on comfort and a life “sold out” to Jesus, the only option, it seems, is to embrace a radical path. Push this disposition from the individual to the polis and you’ve got our postliberal infatuations with integralism or “magisterial Protestantism,” the Simple Way to the Catholic Church’s centuries of monasteries.

As an aspiring medical missionary ten years ago, I was swayed by this sort of rhetoric. Perhaps it helped push me along into my current vocation, where I serve at a teaching hospital in East Africa to disciple and train young doctors. Yet I also wince a little when I hear it today, in no small part because my somewhat “radical” life does not feel very radical when I get up every day, feed my children breakfast, go to work, see patients, teach medical professionals, butt my head against various institutional forces, try to avoid looking at Twitter too much, fill out paperwork, come home, play with my kids, put them to bed, go to bed myself, and then start the whole process over again. The habits and spiritual disciplines I use to get through my day do not, in general, rely on the same sort of verses and exhortations that got my blood pumping about serving the poor when I was still in college.

What I found powerful about a new biography of Jean Vanier by Anne-Sophie Constant was how deftly Vanier walked this line between the radical and the ordinary in his life and how downright accessible his example of a life of service comes across. Weaving Vanier’s writing and poetry throughout the book with insights drawn from lengthy interviews, Constant draws a picture of a man who is at once extraordinary and ordinary, a hero who simply had the courage to live life with difficult people. Based on how many L’Arche communities there are in the world today emulating Vanier’s example, it is clear that his choices, while sharply orthogonal to mainstream cultural forces, are still not too radical for many to follow.

A Beautiful Life

Constant, a longtime friend of Vanier, begins the story with Vanier’s parents. His father Georges, ranked number one on a 1998 Maclean’s list of the most important Canadians of all time, lost a leg in World War I and eventually became Governor General of Canada. Georges Vanier was appointed Canadian ambassador to France in 1939, but almost as soon as they reached Paris the family had to flee the invading Nazis. Jean recalls one particularly painful moment on the cargo ship they had crammed into. He was looking over the side down to a ferry full of weeping refugees who were denied boarding because there was barely room or supplies for those already on board. The family eventually made it to London and back to Canada, but Jean was haunted by his memory of those left behind in Europe and deeply affected by ongoing news of the war.

Despite only being thirteen, Vanier asked to join the Navy so that he could join the war effort; he proposed joining the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, England. His sister had already joined the military and his father was already a decorated hero; Constant suggests that Jean was also perhaps trying to get out of the shadow of his older brothers (who were performing much better than he in school) or escape his mother’s “stifling” grasp. In any case, he was as serious about the idea as any thirteen-year-old can be and his father granted him permission to go, saying: “You know, we mustn’t clip the child’s wings. We don’t know what he might become later.”

Jean studied for three years at the naval college, becoming a “cadet captain” despite being a Canadian and a Catholic in a school that was mostly British Anglicans. He graduated as a midshipman in 1945, traveling first with the British royal family on state visits (where he danced with Princess Margaret) and visiting with his father (once again the Canadian ambassador to France), where he met such luminaries as Jacques Maritain and the future Pope John XXIII. Despite his excellent performance in the Navy and the opportunity to perhaps follow in his father’s footsteps, he still felt a longing for what one might call a deeper relationship with God. He started praying the Daily Office throughout the day and night and used his shore leave while docked in New York to visit Friendship House in Harlem, a lay religious community for the poor that he had read about in Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. While there, he found a mixed-race community dedicated to serving the poor and praying for the world that (in his words) “captivated” him and helped push him into his next dramatic decision.

Jean left the Navy in 1950, considering the priesthood or a cloistered life (as his older brother did in 1946). As he tried to discern his next steps, Jean began studying at an ecumenical institute in France called Eau Vive under the tutelage of director Father Thomas Philippe. He began reading mystics and studying Latin, anticipating that he would eventually become a priest. He became embroiled in a political conflict at the institute wherein Fr. Thomas named Jean director when he was disciplined by church authorities in Rome, but Jean was eventually forced out. He ended up getting a Th.D. from the Catholic Institute of Paris and began to teach, but was not ready to commit to teaching as a career and was a bit aimless until the Christmas of 1963.

It was then that Jean attended a Christmas play put on by the residents of Val Fleuri, a psychiatric institution near Trosly, where his friend Fr. Thomas had been invited to be the chaplain. Jean was struck by the patients’ desire for a relationship and their eagerness to see him again, which spurred him on to visit other psychiatric institutions and discover the horrifying conditions that isolated and tormented people suffering from intellectual disabilities. Moved by their plight, he made the bold leap of inviting three men from a nearby care home that had eighty people in a space designed for forty to live with him in a little house in Trosly with no bathroom. L’Arche was born. One of the men was so shaken by the move that he had to leave after one night, but Jean’s loving persistence in helping care for the other two men instantly grabbed the attention of others.

A network of friends and advocates for the disabled (including some social workers and psychiatrists) became involved, and by 1965 L’Arche was caring for fifty people in a community setting after Val Fleuri was unexpectedly turned over to Vanier and absorbed into L’Arche. He sent out newsletters, began writing books, and spoke wherever he was invited; without any intention or plan L’Arche grew quickly into an international organization as people around the world were inspired to follow in Vanier’s footsteps. He continued to live in Trosly and participate in the first community that he had founded, but he also helped shepherd and mentor those who started L’Arche communities across the world. In 1971, he helped to found Faith and Light, an organization dedicated to fostering friendships and encouraging prayer among people with disabilities that led hundreds of disabled people and their caregivers on an unprecedented international pilgrimage to Lourdes.

His pace of speaking and visiting was intense in the decade after founding L’Arche, but almost as quickly as the flame began to spread Jean began to back off. He stepped down from his role as International Director in 1975 and then from his role at the Trosly community in 1980. He remained a member of the community and advisor to those working in L’Arche communities around the world, but never again held a formal leadership position in the organization until his death earlier this year.

Challenge and Hope

Constant’s telling of the story is accessible and moving, if a bit underdeveloped: the tone of the book almost feels as if it is written for students, and perhaps it ought to be branded towards that audience. There are numerous places where I wished Constant had delved deeper into Vanier’s written work (over twenty books!) or had thought to draw a more complete picture of his theology and ethics, but oftentimes a single quote is thrown in before moving on to the next subject.

The book also makes a jarring shift from a chronological organization to a topical one once the story of founding the first L’Arche community in Trosly is finished, and here the book is harder to follow. We get the sense that Vanier was still extremely busy with activities all over the world, but the only story that is told in detail is that of the international pilgrimage to Lourdes. This narrative exemplifies Faith and Light’s work and gives us insight into Vanier’s heart, but by comparison the other material in the latter chapters feels disjointed. Still, the book leaves any reader with enough to chew on, even if it’s not an exhaustive history of Vanier’s life and thought.

Vanier’s heartwarming affection for those in need and his stubborn dedication to care for them feels like perfect fodder for a feel-good meme that appears on one’s timeline in between stories about war and debates about postliberalism. Yet both his affection and his dedication are also radical and prophetic in a world that treats intellectual capacity as the sine qua non of personhood and celebrates radical, individual freedom from constraints as the greatest good.

Simultaneously, Vanier’s work is rather novel and (as Constant reminds us) reflects the best of what Vatican II sought to offer the world: a vision for service and sacrifice among the vulnerable, saturated in prayer and holy longing. By bringing in the best people that his connections could draw, connecting with state institutions for funding, and (albeit unintentionally) launching an international movement, Vanier’s labor on behalf of the disabled created something new and beautiful for people who previously would only have access to such care if they were extraordinarily fortunate.

“Thinking about it today, I don’t know how I held up,” he writes. “It was crazy! We had so few assistants, while the men at Val Fleuri were very troubled and explosive. Fortunately, I was naïve. I had the impression that Jesus was present in all the difficulty and the chaos, and that he would help us. It was only by God’s grace that I was able to hold up, because humanly it was impossible.”

A lot of good things seem “humanly impossible” these days: Passing on our faith to the next generation. Creating a culture that celebrates life rather than death. Overcoming the demonic powers that draw human beings into racial hatred and exclusion or hatred of our own natural bodies and perversion. Providing for or protecting the millions of people around the world who see their lives cut short by poverty, disease, or war. Even simply doing good in the name of Christ sometimes seems like an act of naivety, bound to invite some lawsuit.

We could all use a little of Jean Vanier’s fortunate naivety. Is it radical? Certainly, in some ways. We may not all see the same sort of results, but with the sort of mindset he cultivated and encouraged, results would hardly matter as much. In fact, moving away from the expectation that a life of obedience, faithfulness, and service will yield grand results might be the healthiest antidote to the radical urge’s tendency to burn us out and crush our souls.

Reframing from the “radical” to “fortunate naivety” might also be a better way to get more people to sign up for such a life. A society that values prosperity, achievement, independence, and intellectual prowess indeed might judge a life like Vanier’s “radical” because his conformity to the love of Christ led him on a path so distinct from what one might expect from a Governor General’s son. But when we emphasize this radicalism, we attract the people who are already fed up with our wayward society while turning off the people who think they might have in them. Might we have better success in our movements, whether political or ecclesiastical, if we toned down the radical rhetoric and emphasized how you just have to be a little more naive about what you can do for people who need to be loved?

Whichever rhetorical tack we choose, there are still countless vulnerable people hidden in our own communities or across the world, and the people who are able to read about Jean Vanier’s life have a wealth of resources to share with them. Perhaps the greatest is simply time and presence, those things that the totems of our digital age are draining the most slyly as they cultivate a banal cynicism. Vanier was the sort of person that we desperately need an army of; hopefully it is not naive to say that an army of people like him are out there, ready to love others like he did if only they could chuck their cynicism.

Matthew Loftus teaches and practices Family Medicine in Baltimore and East Africa. You can learn more about his work and writing at MatthewAndMaggie.org.