By Alex Pappademas & Joan LeMay.

University of Texas Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 280 pages, $35.

Reviewed by Asher Gelzer-Govatos.

Steely Dan, those infamously reclusive jesters of 1970s radio rock, have undergone a mini-revival over the past few years, suddenly becoming cool again, the subject of Atlantic essays and viral tribute accounts on X/Twitter. A surprising amount of this enthusiasm springs from people my age (mid-30s) and younger, people barely old enough to remember the band’s controversial Best Album Grammy win over Eminem back in 2000, let alone the original glory days of Walter Becker, Donald Fagen, and their ever-rotating cast of accompanying musicians.

On the surface, The Dan seems like a perfect band to be resuscitated by our current cultural cognoscenti: named after an adult toy from William S. Burroughs’s novel Naked Lunch, the band always exhibited a countercultural edge that turned Fagen and Becker into the mirror image of their afriendly rivals The Eagles—a band with a reputation for being just dull enough to please the masses. And Becker and Fagen, who met as students at Bard, long a hippiesh alternative to the Ivies, both bore a certain animus to the mainstream of American life in the post-war period. They transformed that distaste into music that cut through the glamors of rock star life with satirical sharpness. Even their radio mainstays, songs like “Do It Again,” “Reelin’ in the Years,” and “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” have a jagged quality when played next to the “Take It Easy” set. Steely Dan practiced what it preached, too, abstaining from playing live shows during its heyday, a refusal that only added to its mystique as a band that could not be bought and sold.

Yet I suspect that one reason Steely Dan’s star has risen in our own day is that they cannot be exclusively claimed by cultural progressives. Whatever the personal convictions of Fagen and Becker might have been, their songs capture a certain temperamental conservatism, equal parts cynicism towards the promise of a brighter tomorrow and yearning for a sense of social order long past, that feels right at home in our age of fractured shabbiness. Combine this sensibility with the band’s relentless pursuit of aesthetic perfection, and you have a recipe for music that greatly appeals to a certain segment of young fogeys more indebted to T.S. Eliot than to Charlie Kirk.

That seeming disjunction between style and content is the engine that powers Steely Dan’s songs. Even as they spent months and months in the studio for each album, re-recording little snippets endlessly and layering jazzy riffs on top of each other like a musical croissant, they turned this perfectionism to the end of crafting songs about low-rent losers, dropouts from a broken society. A brief, far from exhaustive list of essential characters from Dan songs: a pornographer luring kids to his basement, a “bookkeeper’s son” who’s holed himself up in a room with a case of dynamite to avoid arrest, a man intent on selling his house in order to devote himself to polishing the car of his personal guru, an LSD supplier to the stars who’s fallen on hard times, and a skeezeball who moves in with his aunt and proceeds to hit on his much younger cousin. While never the objects of “empathy” so sought after in modern discussions of art, these Dan characters emerge as three-dimensional subjects, totems of the dysfunctional society where they, in the words of one Dan narrator, “crawl like a viper through these suburban streets.”

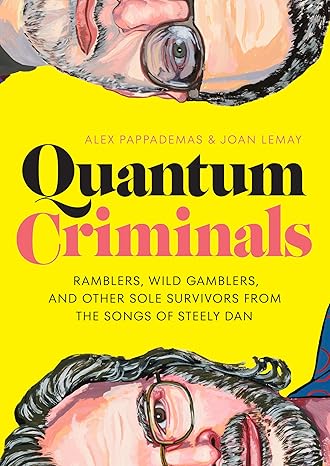

With Quantum Criminals, culture journalist Alex Pappademas attempts to dissect how this misfit duo, indebted to fading musical forms like far-out jazz and Brill Building assembly line pop, came to possess an aura of enduring cool. Rather than giving a straightforward history of the band and its music, Pappademas has crafted a sort of variorum of meditations on the meaning of Steely Dan writ large, chopped up into micro-chapters, each of which takes its name from one of the plethora of strange characters who inhabit the Steely Dan catalog. These chapters come accompanied by a host of paintings by Joan LeMay, whose style splashes in just enough absurdism on top of a base layer of realism to create unsettling effects (my personal favorite is her portrait of The Razor Boy, who in his titular song will “come and take your fancy things away,” and whom LeMay has imbued with the sinister leer of a young Jack Nicholson).

This structural gambit proves to be the book’s biggest strength because no strictly chronological retelling of Steely Dan’s story could capture the chaotic energy of their music. Instead of a totalizing narrative, what Pappademas provides is a series of riffs on motifs, sometimes telling smaller stories from the group’s history or recounting the many musicians, like Michael McDonald, who worked part-time for the band—sometimes unpacking a particular musical choice, such as their relentless quest for the perfect guitar solo to fit their song “Peg,” a process which involved them rejecting takes by nearly a dozen guitarists before settling on one by Jay Graydon (which is indeed the perfect solo for the song). Other sections wander even farther afield; Pappademas devotes a whole chapter to the story of Cathy Berberian, a vocal mimic and John Cage collaborator who gets briefly name-checked in the Dan song “Your Gold Teeth.”

At times, the digressions become frustrating, as when in the chapter on one of the greatest Dan songs, “Dr. Wu,” Pappademas spends barely any time talking about the song itself, instead indulging in a winding reminiscence about hearing the song first as a cover done by punk band The Minutemen. But for the most part, the strategy of diving deep into bizarre details and detours really works because an obsession with oddities is a hallmark of Steely Dan’s style. In an especially flexible, exhilarating section, Pappademas discourses for several paragraphs on a single lyric, “Have you ever seen a squonk’s tears?” from the song “Any Major Dude Will Tell You.” He zips around from considerations of Batman sound effects to Michael Chabon’s novel Wonder Boys before tracing the origin of the word “squonk” to Jorge Luis Borges’s The Book of Extraordinary Creatures, where it refers to, according to Pappademas, “an animal that can literally cry itself into incorporeality.” By forcing readers to burrow down into the meanings behind songs, Pappademas makes us feel like we, too, are inhabiting the world of a Steely Dan song: bewildered by information overload, paralyzed into inaction, but waiting for a revelatory flash of meaning.

Better even than information—which he possesses in enough quantity to surprise even confirmed Steely Dan devotees with nuggets of trivia—Pappademas has that most vital critical tool on his side, which is taste. He emphasizes the right songs and albums, giving the most space to the central run of impeccable albums: Pretzel Logic, Katy Lied, The Royal Scam, Aja, and Gaucho. While some of his omissions are notable, he generally brings to the fore the most important songs in the band’s oeuvre. And he absolutely nails his choice for the quintessential Dan song, “Deacon Blues.” Not only is the song the purest blend of the band’s musical influences (“rock fused with jazz at the molecular level,” as Pappademas puts it), but it also manages, in its depiction of a sad man who yearns to “learn to work the saxophone… play just what I feel,” to perfectly harmonize the band’s satirical and nostalgic sides. The song’s narrator dubs himself “Deacon Blues” because, in Pappademas’ words, “If he can’t be a winner he wants to be the kind of loser whose name also rings out.” That’s as insightful a summation of the Steely Dan ethos as I’ve heard.

As good as Pappademas’ understanding of Steely Dan is, Quantum Criminals does fall prey to some of the typical pitfalls of contemporary cultural journalism. Like many of his fellow white male Gen-X rock critics, Pappademas falls all over himself in an attempt to make sure that you, his hip younger reader, knows that he is with the times, an especially important task when writing a book about two old white dudes. He utters frequent asides to make his positioning clear; is it really necessary, for example, to describe adult film star Ron Jeremy as an “actor and sexual assault defendant”? For the most part, these throat-clearing phrases can be easily ignored, but at times, they obscure his critical vision in significant ways.

That occlusion becomes especially noticeable when Pappademas tries to dissect the racial dynamics at play in a white band leaning so heavily on a musical style, jazz, which originated with African American musicians. There are, of course, real instances in pop music history of exploitation of African American musicians by white artists, but here, the very fact that Becker and Fagen idolized musicians like Charlie Parker and wanted to infuse their music with that passion becomes suspect. So, nearly every time jazz comes up in the book (a lot), Pappademas has to include the disclaimer that, of course, at one level, this is not okay. But really, he wants to have his cake and eat it too, or perhaps we might say that his gut is at war with his head. He’s a true Steely Dan fan, and he can’t deny the magic that occurs when they fold jazz influences into their rock songs. At the same time, he knows that simply enjoying this alchemy is not allowed. So he opts for the worst sort of compromise, engaging in sustained hand-wringing without providing analysis that would actually illuminate.

Ultimately, what these critical failings point to is the slipperiness of Steely Dan as a band, their inability to be shoehorned into any one box. When Pappademas wants to explain the band’s renewed cultural appeal in our present moment, he trots out the usual suspects: Donald Trump, climate change, the unattainable dream of home ownership. He may not be wholly wrong (Trump would make a stellar character in a Dan song), but one could just as easily detect a whole other set of anxieties fuelling younger Dan listeners, including the unreality of online life, the dissolving of traditional bonds of family and place, and the utter banality of current cultural production. Perhaps that’s as it should be. Human grubbiness will always be with us, irrespective of time, place, and political convictions, and so will the desire to transcend that grubbiness. Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, two (in their own words) “gentlemen losers,” knew that well and left in their music a series of windows, both cynical and hopeful, into the human condition.

Asher Gelzer-Govatos is a postdoctoral fellow in the Ogden Honors College at Louisiana State University.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!