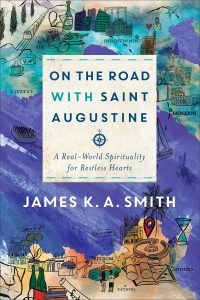

by James K. A. Smith.

Brazos Press, 2019.

Hardcover, 256 pages, $25.

Reviewed by James Davenport

There is an old parable I have often been told. It goes something like this: A man is walking on the road alone. Unaware of where he is or where he is going he finds himself lost and ends up at the bottom of a deep pit. The man begins to cry for help. Along comes a doctor. The man yells up, “Hey doc, can you help me out?” The doctor writes a prescription, throws it down the hole and moves on. Then comes a priest. The man asks, “Father, I’m stuck down here. Can you help me?” The priest scribbles some prayers on a piece of paper, throws them into the pit, and moves on. The man continues to yell. Then along comes a friend. The man yells up, “Hey, Gus, it’s me. Can you help me out?” And the friend jumps in the hole. The man looks at his friend and says, “Are you stupid? Now we’re both down here.” The friend says, “Yeah, but I’ve been down here before and I know the way out.”

That parabolic friend for Jamie Smith, and for many others including myself, is Saint Augustine. Smith has shown us just how this works in his new book, On the Road with Saint Augustine, a beautifully philosophical and deeply human reflection on postmodern life. He’s not writing as a curmudgeon demanding that you straighten up and get your act together. Rather, he’s writing to introduce you to a friend, to say, “Yeah, you aren’t the first to deal with that or mess up like that or have that doubt or fear. Do you know who taught me to deal with these things? Augustine. Let me tell you about him.”

Smith’s latest book comes in two parts, the first being an orientation to his view of the human condition. He highlights in particular our human tendency to leave. Smith writes: “It might be liberation or escape. It might be a million other reasons, but we all leave.” This I find to be palpably true today. It is not necessarily a physical leaving—it might be spiritual, philosophical, or religious. We all leave that place where we started. This is at the core of the book. Recognizing that there is truth in the “life is a journey” trope, Smith constructs (with guidance from the existentialists and Augustine) a refugee spirituality for the postmodern person.

Smith identifies the two spiritualities to each side of the one he would like to construct. These are the Odyssean and Sisyphean, which find their founders, so to speak, in Homer and Camus (and other existentialists), respectively. The Odyssean spirituality is one that many see as the classic Western one, often associated with Christianity. Smith describes it in this way: “The journey is one of our oldest tropes for the adventure of being human. In many cases, the template is Odyssean: departure and return, adventure and homecoming, from bon voyage to welcome home.”

Opposed to this is the Sisyphean narrative, which Smith presents in the frame of Camus. Camus’s spirituality, as Smith describes it, is a spirituality of the road:

The condition is exile, and happiness is embracing it … The feat, the trick, is to learn how “to live without appeal.” Exile is the kingdom … Imagine Sisyphus as a pilgrim caught in a loop, arrival always eluding him, accomplishment perpetually undermined. Sisyphus is the absurd hero for Camus because he embraces this perpetual pilgrimage of futility.

The road is life to Camus. There is no home to go back to or destination towards which one is headed.

The alternative Smith wants to present to these two ways of viewing the human condition is his deeply Augustinian “refugee spirituality.” Smith writes: “What if the human condition was understood not as Odyssean (a neat and tidy return) or Sisyphean (learning to get over your hope for home), but as being like the experience of a refugee?” Human as cosmic refugee—that is the true north to which Smith would orient his readers. Life’s journey is not returning to something you once knew, neither is it giving up the idea of home. Rather, life’s journey is going to a new place—a home you do not yet know.

Once we have our orientation, we enter part two, “Detours on the Way to Myself.” Here we get Smith’s (much-needed) Augustinian guide to postmodern life. With Camus and Heidegger in one hand and Augustine in the other, Smith takes us on a journey through our search for freedom, recognition, intimacy, independence, friendship, rationality, justice, life, and (a particular emphasis) identity. This section is ordered around questions that are essential to the postmodern human being. What do I want when I want to be noticed? … when I want to belong? … when I want to change the world? … when I want to live? … when I want to be liberated? … and when I want to leave? These are questions of authenticity and identity that are fundamental to the way we understand ourselves as human today. Smith’s introduction to the section is evocative: “Wherein we embark, looking for ourselves, visiting the way stations of a hungry soul, wondering where this all might lead—and if there might be an end to our striving.”

While Smith draws mainly on Augustine, this book focuses on other important figures who were greatly influenced by Augustine—most prominently Camus and Heidegger. Such names might incline my reader to expect a book that is more academic than a lay reader might prefer. But Smith here does what so many fail to do, and provides an intellectually honest, and clearly well read, argument in a way that is helpful and never dull. His prose flows in such a way to highlight the truth of his words through their beauty. This alone is reason enough to read the book.

Also worthy of note is the reason that Smith presents Augustine as his guide. This is personal for him, and this is part of what makes this book so deeply human. Smith’s connection with Augustine has been fostered over many years, beginning during his graduate studies at Villanova University, and here he introduces the reader to the great saint as a friend. Smith gives many beautiful examples not only of Augustine’s impact on his own life, but also of his personal connection. As Smith puts it, Augustine is a character in a story who he can see and say, “That’s me.” A great example of the power of this personal connection is when Smith tells the story of visiting the saint’s relics, connecting it with the famous story of Augustine’s own conversion:

Not even my Protestant heart can resist the frisson of proximity here. I seem to have the space to myself, though [my wife] Deanna, my Alypius, is nearby, just like Augustine in the garden. A silence descends on everything. I’m standing before the urn that holds Augustine’s mortal remains, and for the first moment I think: “I can’t believe I’m this close to him.” But that geographical inclination gives way, and I realize that the sacred charge that enchants this place for me is an odd sense of arrival, the convergence of two journeys. I’ve been on the road with this saint for what feels like a lifetime, and here we finally cross paths and all I can think to say is, “Thank you.”

I recently converted to Roman Catholicism. My guide to the Church and now in the Church is Saint Augustine, my confirmation saint. I feel this connection about which Smith writes. Through his Confessions and his other works, he guided me to the grace of Christ. Smith here highlights exactly the things that attracted me to Augustine. Augustine is a “witness authority” to the struggles of the postmodern person. He’s not antiquated and unable to speak to our condition. When Augustine jumped down into the parabolic pit in which I had found myself, it was as if he said to me, “let me show you the truth.”

Smith’s description of Augustine’s guidance reminds me of the old Tom T. Hall song, “That’s How I Got to Memphis.” In the first line, Hall sings, “If you love somebody enough, you’ll follow wherever they go. That’s how I got to Memphis, that’s how I got to Memphis.” We are brought to the places we end up by love. Love orders our time on the road. And so it is important that we love the right things. This is something Augustine knew deeply, and something Smith points out to his reader time and time again. You might find yourself in a hole as a postmodern person, whether you are Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, or whatever else. What Smith has done here is not to provide a spirituality for postmodern Protestants. Rather, he has seen you down deep in this pit and realized Augustine knows the way out—and more than that, how to orient and order yourself so that you can find your way outside the pit. It seems to me that Augustine can teach you to love the right thing so that you end up in the right Memphis.

James Davenport is a senior at the Templeton Honors College at Eastern University, where he studies Politics, Philosophy, and Theology. James tweets at @mrJSDavenport