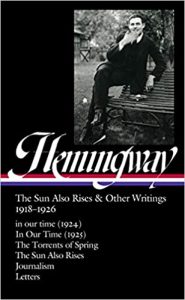

Edited by Robert W. Trogdon.

Library of America, 2020.

Hardcover, 863 pages, $35.

Reviewed by Frank Freeman

It was surely no accident that the first Library of America volume devoted to Ernest Hemingway was released on the first day of autumn, or, if it wasn’t, it was a happy accident. For Hemingway’s work has always had an autumnal feel to it: because so often its theme is death, but also because of its bracing quality. As Hemingway wrote to F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Summer’s a discouraging time to work—You dont feel death coming on the way it does in the fall when the boys really put pen to paper.” (Hemingway’s spelling was hit or miss.)

The opening section of this volume, “Selected Journalism 1920–1923,” includes mostly work Hemingway wrote for the Kansas City Star and Toronto Star. All his future themes appear in these articles in a popularized jocular form, along with a sardonic wit Hemingway did not often display in his fiction. In this journalism, after driving ambulances along the Austrian-Italian front in World War I and being wounded, he began to learn to write. As he told George Plimpton in his 1958 interview for The Paris Review, “On the [Kansas City Star] you were forced to learn to write a simple declarative sentence.… Newspaper work will not harm a young writer and could help him if he gets out of it in time.” By “Newspaper work,” Hemingway must have meant being on the daily staff of a newspaper, because he wrote occasional journalism for most of his career.

One begins to notice, while reading the journalism, such lines as (in “American Bohemians in Paris a Weird Lot”), “[i]t is a strange-acting and strange-looking breed that crowd the tables of the Café Rotonde. They have all striven so hard for a careless individuality of clothing that they have achieved a sort of uniformity of eccentricity.” This was the kind of writing Hemingway would later eschew, but it puts to rest the idea he was incapable of writing it. That he was a “boys writer” who never grew up. He was a sophisticated (in a good sense) artist who wrote the way he did for a reason.

Noteworthy in the journalism are the subjects, given to Hemingway by history, of refugees and the rise of Fascism. He wrote about Greek Christians having to flee the Turks and he also interviewed Mussolini. The scenes of refugees tramping through the mud with all their possessions sharpened his writing:

Their brilliant peasant costumes are soaked and draggled. Chickens dangle by their feet from the carts. Calves nuzzle at the draught cattle wherever a jam halts the stream. An old man marches under a young pig, a scythe and a gun, with a chicken tied to his scythe. A husband spreads a blanket over a woman in labor in one of the carts to keep off the driving rain. She is the only person making a sound. Her little daughter looks at her in horror and begins to cry. And the procession keeps moving.

Note the specificity, the active voice and the vivid verbs. Hemingway is beginning to find his voice, which stays away from abstract words and describes things as they are, not as we would like them to be, and does so in such a way that the reader isn’t told what to feel but feels it as he or she reads.

In his article about Mussolini, “Mussolini, Europe’s Prize Bluffer More Like Bottomley than Napoleon,” Hemingway mocks the dictator for pretending to intensely study a book while being photographed and then says (though the reader wonders if it really happened) the book was a French-Italian dictionary held upside down. But later, in words that seem prophetic of our own interesting times, Hemingway writes, “Mussolini isn’t a fool and he is a great organizer. But it is a very dangerous thing to organize the patriotism of a nation if you are not sincere.…”

The next work in the volume, in our time, was published as a sort of chapbook in 1924. It consists of short vignettes Hemingway had been working on in his notebooks. In these he strove to distill life into a clear, plain, and yet poetic style. Hemingway dedicated it partly to Captain Eric Edward Dorman-Smith, whom he called “Chink,” an Irishman in the English army, one of the few friends he did not have a falling-out with and the source, sometimes close to verbatim, of some of the vignettes, such as “chapter 4,” the entire text of which follows:

We were in a garden at Mons. Young Buckley came in with his patrol from across the river. The first German I saw climbed up over the garden wall. We waited till he got one leg over and then potted him. He had so much equipment on and looked awfully surprised and fell down into the garden. Then three more came over further down the wall. We shot them. They all came just like that.

It seems as if the Great War had shaken the world so much one could not write like the Edwardians anymore. One had to say, as Robert Graves entitled his memoir, Good-bye to All That. (Although one could argue that the Inklings did not, and fared well.)

These vignettes, some revised, appear in Hemingway’s next book, In Our Time, in 1925, published by Boni and Liveright and praised by Edmund Wilson. In Our Time includes short stories with the vignettes, still labeled as “Chapters,” interleaved between them. There are classics of the form here—“Indian Camp,” “The Doctor and the Doctor’s Wife,” “The Three-Day Blow,” “The Battler,” “Soldier’s Home,” and “Big Two-Hearted River,” parts one and two. There are others that are middling, for Hemingway, and a couple that are closer to chaff: “Mr. and Mrs. Elliott,” a cruel story about two people Hemingway knew, and “My Old Man, which, though it got included in The Best Short Stories of 1923, is a rather sentimental story. These stories are reminders that cruelty and sentimentality, which occasionally mar some of Hemingway’s work, were always part of his make-up.

But other stories are exquisite. Ford Madox Ford wrote in an introduction to A Farewell to Arms, that reading Hemingway’s prose was akin to gazing at the pebbles at the bottom of a clear mountain stream. Perhaps this is the kind of passage, taken from “Big Two-Hearted River, Part II,” that he had in mind:

He stepped into the stream. It was a shock. His trouser clung tight to his legs. His shoes felt the gravel. The water was a rising cold shock.

Rushing, the current sucked against his legs. Where he stepped in, the water was over his knees. He waded with the current. The gravel slid under his shoes. He looked down at the swirl of water below each leg and tipped up the bottle to get a grasshopper.

The first grasshopper gave a jump in the neck of the bottle and went out into the water. He was sucked under in the whirl by Nick’s right leg and came to the surface a little way down stream. He floated rapidly, kicking. In a quick circle, breaking the smooth surface of the water, he disappeared. A trout had taken him.

It would be good if we could skip ahead to Hemingway’s novel, The Sun Also Rises. But we can’t because, after banging out a first draft of that novel, he then wrote, in two weeks, a comic novel entitled The Torrents of Spring: A Romantic Novel in Honor of the Passing of a Great Race, a parody of Sherwood Anderson, one of Hemingway’s first mentors. Anderson had urged Hemingway and his first wife Hadley to go to Paris and written letters of introduction to various literary celebrities, including Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein. Hemingway wrote this book to get out of a contract with Boni and Liveright, who had not marketed his book very well, and so he could go over to Scribner’s where his new friend Scott Fitzgerald was happy. This seems evident and perhaps forgivable, but that he mocked Anderson’s work in so doing, is not. Hadley and John Dos Passos, his friend and fellow writer, told him not to do it. It got him out of the contract and into Scribner’s but it ruined his friendship with Anderson. This was his first great moral failure, and the second was soon to follow. But karma would come around when E. B. White wrote his own parody of Hemingway called “Across the Street and Into the Grill,” which begins, “This is my last and best and true and only meal, thought Mr. Perley as he descended at noon and swung east on the beat-up sidewalk of Forty-fifth Street. Just ahead of him was the girl from the reception desk. I am a little fleshed up around the crook of the elbow, thought Mr. Perley, but I commute good.”

The Torrents of Spring and The Sun Also Rises were both published in 1926, the former, appropriately enough, in the spring, the latter in the fall. If this wasn’t enough, Hadley discovered Hemingway was having an affair with their friend, Pauline Pfeiffer. By the end of the year, Hadley would be asking for a divorce. The domestic turmoil appears to have fueled Hemingway’s creativity; whether it was worth it or whether the work would still have been produced is another question. Trust the tale, not the teller, as D. H. Lawrence said.

The Sun Also Rises is about a group of expatriates who attend the summer bullfighting festival in Pamplona, Spain. The protagonist is a genitally wounded veteran, Jake Barnes, who is in love with an Englishwoman, Brett Ashley, who has a Lady in front of her name because of a past marriage to nobility. She requites Jake’s love but because of the wound their love cannot be consummated. Not that Brett would be faithful, for she is a sexually voracious woman, perhaps, it is hinted, because she has been abused by men early in her life.

There are others in the group: Mike, Brett’s fiancé, Robert Cohn, and Bill Gorton, Jake’s buddy. The novel is about a pilgrimage. It begins in Paris where there is a lot of drinking and dancing going on (though Jake is seen dutifully working as a journalist), moves to Spain where there is still a lot of drinking and dancing, but which is redeemed by fishing and fellowship and the “tragedy,” as Hemingway liked to call it, of the bullfight. Jake is a bad Catholic, who goes to Mass and occasionally drops into a church to pray, but his beliefs seem not to affect his behavior much. However they do serve as a counterweight to the indulgence of the group as a whole. As does the code of the bullfight and the passion of its true fans who have aficion (passion) for it. Jake talks about this when he describes the hotel owner, Montoya, whose hotel Jake stays at every summer (although one feels at novel’s end this will be the last summer he does):

He [Montoya] smiled again. He always smiled as though bull-fighting were a very special secret between the two of us; a rather shocking but really very deep secret that we knew about. He always smiled as though there were something lewd about the secret to outsiders, but that it was something that we understood. It would not do to expose it to people who would not understand.

The one expatriate who does not understand it is Robert Cohn (there is some antisemitism in Hemingway’s treatment of him), who ruins the festival with his obsession with Brett. Jake and Brett both understand bullfighting, have aficion, but their confused loves contribute to the debacle of the novel’s ending.

The novel includes some of Hemingway’s most beautiful passages. Most of these have to do with the Spanish countryside, the Spanish people, and bullfighting. Hemingway himself said part of the point of the novel, as evidenced by its quotation from Ecclesiastes to preface it (along with Gertrude Stein’s famous saying, “You are all a lost generation.”) is that the hero is the earth itself, which keeps on going despite all of humanity’s dramas. And which, if turned to humbly, provides healing. This is shown when Jake spends a few days at a Spanish beach resort, San Sebastian. He swims and eats and drinks and reads the newspapers and there is the suggestion, though it is never proclaimed, that the ocean swims are cleansing Jake of the corruption he has been a part of:

I undressed in one of the bath-cabins, crossed the narrow line of beach and went into the water. I swam out, trying to swim through the rollers, but having to dive sometimes. Then in the quiet water I turned and floated. Floating I saw only the sky, and felt the drop and lift of the swells. I swam back to the surf and coasted in, face down, on a big roller, then turned and swam, trying to keep in the trough, and I turned and swam out to the raft. The water was buoyant and cold. It felt as though you could never sink. I swam slowly, it seemed like a long swim with the high tide, and then pulled up on the raft and sat, dripping on the boards that were becoming hot in the sun.… The raft rocked with the motion of the water.

It is only an interlude—there’s a telegram dragging him back into the world after the swim—but nature has provided a healing respite.

In the last section of this volume, “Selected Letters, 1918–1926,” you get the unvarnished Hemingway. He can be a wonderful friend, sensitive lover, dutiful son, but also one spiteful, prevaricating, braggart of a man. There are letters to family and friends, the latter including Anderson, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, Edmund Wilson, and Maxwell Perkins. One could pick out some vile comments Hemingway made about other writers, but the following, written to his father, seems to come from the genuine deepest part of the man:

You see I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not to just depict life—or criticize it—but to actually make it alive. So that when you have read something by me you actually experience the thing. You cant do this without putting in the bad and the ugly as well as what is beautiful. Because if it is all beautiful you cant believe in it. Things arent that way. It is only by showing both sides—3 dimensions and if possible 4 that you can write the way I want to.

Robert W. Trodgon has done a splendid editing job. The “Chronology,” “Note on the Texts,” and “Notes,” are all superb, the best and most representative of the journalism and letters are included. Hemingway aficionados will eagerly look forward to the rest of the volumes.

Looked at from the viewpoint of ancient Greek philosophy, Hemingway’s life was a battle between a Stoicism gleaned from his upbringing and an Epicureanism he picked up along the way of his life. Of the four classic Stoic virtues—courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom—the cause of his slow downfall, relieved with spectacular comebacks—was a lack of temperance. Courage he had aplenty, justice and wisdom in him ebbed and flowed, but he was often not in control of his physical and emotional life. Inherited mental illness, though, was a big part of this.

One of the best descriptions of Hemingway is in a quote from Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, with which Peter Griffin prefaced his biography of Hemingway’s early life, Along With Youth: “He was the sort of boy that becomes a clown and a lout as soon as he is not understood or feels himself held cheap, and again is adorable at the first touch of warmth.”

Frank Freeman writes from Saco, Maine.