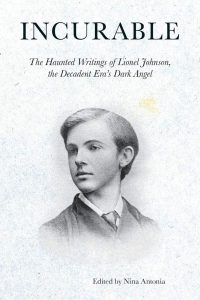

by Lionel Johnson,

edited by Nina Antonia.

Strange Attractor Press, 2019.

Paperback, 216 pages, $20.

Reviewed by Scott Beauchamp

The German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes in The Burnout Society that every age has its signature affliction—paranoid schizophrenia for the Cold War and ADHD for our own time, each malady revealing some essential element of the zeitgeist. Surely the same metaphor works just as well with chemical vices and writers. The neoprimitive “acid fascists” of the 1960s used LSD to pry open their third eyes. Hemingway and Fitzgerald pickled themselves in Paris. In the 1980s, Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis seem to have done enough uppers to convince themselves that their amoral hyper-realism had depth. Following this logic, it was fitting that the British poets and writers of the 1890s, the so-called “Yellow Decade” of decadent aesthetes, fueled their reveries with absinthe, the psychoactive spirit known as la fée verte. And surely if that decadent fairy of the fin-de-siècle were personified, it would be in the haunted personage of poet Lionel Johnson.

Born in 1867 to a prosperous and proud military family of noble origins, Johnson eschewed the respectability of traditional professions in favor of literary pursuits. After graduating from Oxford in 1890, Johnson moved to London and began his literary career in earnest. According to Nina Antonia’s introduction to Incurable, the newly published collection of Johnson’s writing, it was in London where Johnson and fellow writers W. B. Yeats, Ernest Dowson, and Arthur Symons formed the famed Rhymers Club. These poets all shared in the excesses of the age, particularly the fascination for occult revery, but they were able to distinguish themselves from the general cacophony of table-tapping and Theosophical indulgences by actually being able to write well.

Incurable showcases some of that ability. It isn’t exhaustive, but from a man who gave us such relatively little output (as compared to, say, Yeats or even Wilde), it is able to give us his greatest hits of poetry, prose, and marginalia. Johnson’s writing is suffused with the gloss of decadent French symbolism, flavored with a dash of Whitman’s barbaric yalp. But just as Johnson never quite gave in to Whitman’s formlessness—he was actually a master of the meter, and his achievements include writing quite inventive formal Latin poetry—neither did he ever succumb to Baudelaire’s picturesque nihilism. Say what you will about the Rhymer’s Club’s embrace of the Gothic, but their hunger for the eternal wasn’t simply literary posturing. Yeats tried to raise the ghost of a dead rose, after all.

This literalness—this using literature in order to feed one’s soul on something just beyond the realm of art—comes through in nearly everything Johnson wrote. Take, for example, the first stanza of his 1890 poem, “The Age of a Dream”:

Imageries of dreams reveal a gracious age:

Black armour, falling lace, and altar lights at morn.

The courtesy of Saints, their gentleness and scorn,

Lights on earth more fair, than shone from Plato’s page:

The courtesy of knights, fair calm, and sacred rage:

The courtesy of love, sorrow for love’s sake borne.

Vanished, those high conceits! Desolate and forlorn,

We hunger against hope for that lost heritage.

Hungering against hope was perhaps the constant theme of nearly everyone working in Johnson’s milieu. For Yeats, that meant turning first towards Irish myth and folklore before turning to Theosophy and magic. For Johnson, it meant moving through the more juvenile elements of Gothicism and entering into communion with the Roman Catholic Church. In a few of these poems you can viscerally feel that movement. As Johnson writes in “The Church of a Dream”:

Sadly, the dead leaves rustle in the whistling wind,

Around the weather-worn, gray church, low down the vale:

The Saints in golden vesture shake before the gale;

The glorious windows shake, where still they dwell enshrined;

Old Saints by long dead, shrivelled hands, long since designed;

There still, although the world autumnal be, and pale,

Still in their golden vestures the old saints prevail;

Alone with Christ, desolate else, left by mankind.

Much Gothic writing is nihilism dressed up in a garish costume. But for Johnson, it was the world sans Christ that was “autumnal” and “pale.” And for him, the church really did provide, if nothing as simple as an answer, then at least a way. A path.

Incurable beautifully preserves a few of Johnson’s letters, going a long ways in helping us to get a sense of the man himself. In one of these, written to his close American friend Louise Imogen Guiney, we get Johnson’s sense of what entering the church meant to an artist like himself, in his defense of Aubrey Beardsley’s conversion to Catholicism. Johnson could well have been writing about himself:

His consciousness of imminent death—the certainty that whatever he might do in art, in thought, in life at all, must be done very soon or never—forced him to face the ultimate questions. I do not for an instant mean that his conversion was a kind of feverish snatching at comfort and peace, a sort of anodyne or opiate for his restless mind: I only mean that, being under sentence of death, in the shadow of it, he was brought swiftly face to face with the values and purposes of life and human activity, and that he ‘co-operated with grace’, as theology puts it, by a more immediate and vivid vision of faith, than is granted to most converts. All that was best in his art, its often intense idealism, its longing to express the ultimate truths of beauty in line and form, its profound imaginativeness, helped to lead him straight to that faith which embraces and explains all human apprehensions of, and cravings for, the last and highest excellences.

Johnson also died young, at thirty-five, from alcohol abuse. Being who he was, he left behind no children but his body of work, which lived on—not only through its influence on Yeats, though especially that—into the twentieth century, presaging as it does much in Modernism generally. Johnson had a fascination of and gift for crafting the arresting image, but what separates him from his Imagist progeny is how the objects Johnson depicts always seem to flash for an instant before dissolving into an ethereal mist. If Imagists followed the notion that the world is all that is the case, Johnson’s prose was struck through with the ephemerality of life itself. In Johnson’s poetry, as a fellow mystic said sixty years later, life is a dream already over.

This sensitivity to eternity, this hunger for it, kept Johnson straining against the social and spiritual constrictions of his age towards something more profound. This appetite, and the effect it had on his art, made him something more than just another decadent or a vapid dandy. It made him a tragic mystic, resonating with something beyond the foppishness of his age.

Scott Beauchamp is a writer and infantry veteran whose previous work has appeared in the Paris Review, The American Conservative, and Bookforum, among other places. He lives in Maine.