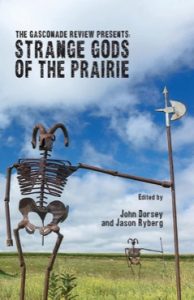

edited by Jason Ryberg and John Dorsey.

Spartan Press, 2021.

Paperback, 250 pages, $15.

Reviewed by Christopher Landrum

Strange Gods of the Prairie is an anthology by the Gasconade Review of Bell, Missouri, comprising 150 poetic works across 228 pages by fifty contemporary poets at three poems each. The writers range from all across the country, and at least one is from the United Kingdom.

In this volume, readers will sometimes hear what social critic Ivan Illich (1926–2002) meant by an “individual freedom realized in personal interdependence.” Indeed, Strange Gods might be called a “convivial” anthology, following Illich’s use of the term that whatever is “convivial” is “opposite of industrial productivity,” and instead includes “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment.”

That is to say, the Gasconade Review is not one of the big five present-day American publishers, and therefore, the Review can probably never match the “industrial productivity” of the latter. But its production of Strange Gods of the Prairie—containing such a large chunk of poetry quarried and refined by so many diverse writers from the United States—does indeed provide readers with what Illich called an “autonomous and creative intercourse” among contemporary poets as well as an intercourse of those poets “with their environment.”

The cover art by artist(s) unknown is magnificent but potent. It contains not only bright landscape photography, but foreboding sculpture. Editors John Dorsey and Jason Ryberg have omitted any manifesto concerning their intentions behind collecting these particular poems and poets, but two prominent themes (or moods) emerge upon first encounter with Strange Gods, which might be called the wild and the quiet. These moods fail to clash, though occasionally they may overlap, even harmonize. The two moods, however, do constitute a convivial whole, intermeshed rather than polarized.

The tranquil mood found in Strange Gods is reminiscent of the overall atmosphere readers get from works like German novelist Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922), the novel Mon (The Gate) (1910) by Japanese writer Natsume Soseki (1867–1916), and even the French Pêcheur d’Islande (An Iceland Fisherman) (1886) by Pierre Loti (1850–1923). In these poetic novels nothing feels old, though at the same time nothing seems fast-paced. This aesthetic of ageless contemplation runs through parts of Strange Gods in such poems as:

- “What Causes Earth to Spin” by Matthew Cooper (Kansas), particularly its last several lines, which seem to share similar elements with the infusion of Vangelis’s music, Ridley Scott’s directing, and Rutger Hauer’s voice improvising the “tears in rain” soliloquy at the end of the film Blade Runner (1982).

- “Song” by William Taylor Jr. (California), which appears to be an ode to a barren landscape, once inhabited but now abandoned. Yet its narrator seems to speak to the landscape as a person confronting it for the first time. The speaker, moreover, may not be the one who first abandoned the land.

- “The Path of the Flood” by Scott Silsbe (Michigan), where readers find themselves basking in warm-sun memory, though not burned by nostalgia.

In contrast with this mood of contemplation amid timelessness take Hemingway: in whose “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” The Sun Also Rises, and The Old Man and the Sea—as also in poetic novels by others, like The Lord of the Rings and John Gardner’s Grendel (1971)—there is a shared slow pace of genuine contemplation. But the world and the characters of these works feel old rather than young. They are time-bound to their created worlds rather than timeless (“timeless” in the sense of bearing no age, unhindered by any captivity from any so-called “spirit of the times”).

In both the prose and poetry of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, in much of Wordsworth’s body of work, but also for Hemingway’s narrators in “The Snows” and The Sun, as well the characters of Hemingway’s Old Man and Gardner’s Grendel—they are always looking back from where they have been, looking back at what has changed, looking back at what once was. It is this abundance of looking back in these works that stirs the feeling-of-feeling-old, coupled with an aching awareness of how ancient the earth still remains. And though the thoughts are quite varied in Strange Gods, there comes across a shared feeling of near-silence accompanied with serenity (but all without the heavy reliance on the backward gaze) in poems like:

- “Make The Connection” by Linnet Phoenix (Somerset, UK), and how an epiphany does not have to be an overwhelming reckoning, but a realization that may slowly, subtly seep into the front of one’s mind.

- “Conceal and Carry,” by Linda Rocheleau (North Carolina) and its contemplations about how what we hide shapes who we are—lines of thought similar to the way philosopher Walter Kaufmann (1921–1980) once asked: “Does one not write books precisely to conceal what one harbors?” for “Every philosophy also conceals a philosophy.”

Readers will also find coursing through this anthology—and quite in contrast to the quiet—a wild, spacious mood. This sense of vitality has its precursors in the battle cries of Joan of Arc, the healing power of laughter conveyed throughout Tristram Shandy (1761–67) by its sickly author Laurence Sterne, the roar of guffaw and gusto in a Gilbert and Sullivan song—though in the case of Strange Gods, without need of rhyme.

It is a wildness produced in America as well, seen in such things as the clearness and sharpness of the crystal-glass rhetoric of Frederick Douglass, in the “Hoedown” movement of Copeland’s ballet Rodeo (1942), and in Elmer Bernstein’s explosive score to The Magnificent Seven (1960). It is the same jubilant affirmation of the All as said in Psalm 118:24: “This is the day that the Lord hath made. I will rejoice and be glad in it.”

For Strange Gods, such wildness is found in poems like:

- “Jersey Poet” by Luke Kuzmish (Pennsylvania) and the imperative for one to “sew” one’s “wounds” with “shoelaces.”

- “The Way the Story Ends” by Holly Day (Minnesota), which, though not a fairytale, nonetheless contains elements that may constitute what Tolkien once defined as faërie, which, “besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons,” Tolkien tells readers, “holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted.”

- “Flashcuts” by Charlie Brice (Pennsylvania) and how the failure of language in an emergency room induces a lot of chewing and choking.

- “Total Honesty” by Ace Boggess (West Virginia) with its “bacon” beside “tears.”

- “First Book” by Wayne F. Burke (Vermont) and its quirky, whimsical honesty.

This wild, spacious mood of Strange Gods involves an untamed cry for freedom and movement. Philosopher-geographer Yi-Fu Tuan comes very close to explaining it when, in his classic Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (1977), he writes:

Spaciousness is closely associated with the sense of being free. Freedom implies space; it means having the power and enough room in which to act. Being free has several levels of meaning. Fundamental is the ability to transcend the present condition, and this transcendence is most simply manifest as the elementary power to move.

Just as panoramic photography can depict either a wild or a quiet mood, so too is there joy in the quiet, and joy in the wild, and joy within the quiet within the wild. It is not surprising, therefore, that hybrid poems containing both moods of stillness alongside moods swiftly stirring are present in this anthology:

- “Strange Gods of the Prairie” by James Duncan (New York) contains both the deep restlessness of a reckless spirit hankering for release—yet a restlessness also able to see the landscape as a place of quiet peace.

- “The Open Road” by Tanya Rakh (Texas) mixes a sense of contentment with restlessness via its refrains of “blood,” and “drums” beside the hum of insects.

- “Wild Things,” by Mela Blust (Pennsylvania) and its pure and simple meditation on a deer in the headlights offers another hybrid of vitality and contemplation.

These works seem equally active and reflective in the moods they evoke, channel, render, manifest, suggest, impart, emit, radiate—in other words, they lead readers to rediscover, as Emerson once did, that “every end is prospective of some other end, which is also temporary; a round and final success nowhere,” because “our music, our poetry, our language itself are not satisfactions, but suggestions.”

After one close reading, the present reviewer has found much satisfaction in most of the poetry in Strange Gods of the Prairie. Like fine wine, one expects this volume to age well in the coming years. And such stability against so-called “liquid modernity” makes for a blessed assurance.

Christopher Landrum’s work has appeared in Fortnightly Review (UK) and the Berlin Review of Books, as well as several central Texas newspapers. He lives in Austin, Texas and writes about what he reads at Bookbread.com.