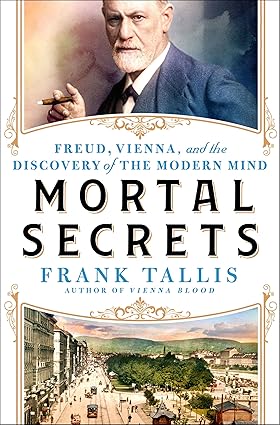

By Frank Tallis.

St. Martin’s Press, 2024.

Hardcover, 496 pages, $31.

Frank Tallis published Mortal Secrets: Freud, Vienna, and the Discovery of the Modern Mind early in 2024. The University Bookman contributor JP O’Malley caught up with Tallis to discuss his latest book.

The Habsburg Empire once stretched across 240,000 square miles of Europe. In Fin de Siècle Vienna, however, many began questioning the once-glorious empire’s future and Austria’s status as a major global power. In November 1899, Neue Freie Presse, a leading Viennese daily newspaper, summarized that feeling of impending doom with a befitting headline: “Postcards from the End of the World.” The article that followed described one Viennese entrepreneur’s efforts to print postcards in anticipation of the apocalypse.

Frank Tallis cites this story in Mortal Secrets: Freud, Vienna, and the Discovery of the Modern Mind. Published earlier this year, the book examines the circuitous relationship between sex, death, Sigmund Freud, and Viennese coffee. “Coffee houses had a special place in Viennese culture. They were intellectual melting-pots, where chemists, violinists, novelists and biologists, theatre directors and mathematicians, all shared the same table and mixed socially,” Tallis explains from his home in London, England. “This cultural fertility had a direct effect on Sigmund Freud’s thinking and his two motivational theories: Eros and Thanatos.”

The Austrian neurologist believed that human beings are ruled by two primary forces: the life instinct (Eros) and the death instinct (Thanatos). Freud claimed these two competing forces work together and often compete to guide and direct human behavior. “Viennese art was obsessed with sex and death. In Freud’s Vienna there were prostitutes on every street corner and there was a lot of pornography going around,” Tallis explains. “But there was a high suicide rate in the city during this time too.”

Tallis is a practicing clinical psychologist who has held lecturing posts in clinical psychology and neuroscience at the Institute of Psychiatry and King’s College, London. In his books, he has also used case studies from his own clinical practice to elaborate on psychoanalytical theory. The Incurable Romantic (2018) and Lovesick (2008), for instance, both explored the relationship between romantic love and mental illness. Changing Minds (1998) and Hidden Minds (2002), meanwhile, documented the history of psychotherapy and the unconscious respectively. Tallis has also published a series of crime novels, the Liebermann Papers Series, (2005-2018), which are set in Fin de Siècle Vienna. In all these books, Freud’s presence and ideas are undoubtedly a significant influence.

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg—a small town in Moravia (today called Příbor in the Czech Republic). When he was four years old, he moved with his family to Vienna where he lived and worked until the last year of his life. He left his beloved Vienna because Nazi Germany annexed Austria in March 1938. Freud and his family fled to London in June 1938. He remained there until his death, aged 83, in September 1939. The Austrian neurologist is often referred to as the founding father of modern psychology. Freud published over 320 works throughout his life, including essays, papers, letters, and books.

His most famous books include The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Totem and Taboo (1913), and Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920). Freud famously used the analogy of an iceberg to describe the three levels of the human mind. On the surface, he claimed, is consciousness. This is the tip of the iceberg, which consists of thoughts that are the focus of our attention in the present moment. Freud said the preconscious consists of all that can be retrieved from memory. In Freud’s view, the unconscious was the third and most significant region of the mind. He believed it contained a reservoir of unpleasant feelings, thoughts, urges, and memories. “Freud’s work on the unconscious has enormous explanatory power,” Tallis explains. “And he often compared psychotherapy to excavating a buried city.”

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, refers to techniques that help individuals change behaviors, thoughts, and emotions that cause problems or distress. Its main aim is to resolve current problems, improve coping skills, and foster behavioral and emotional adjustments in a relatively shorter time frame. Psychoanalysis, by contrast, delves deep into the unconscious to bring about long-term personality change. But “psychoanalysis catalyzed the development of all forms of modern psychotherapy,” as Tallis explains.

Freud first came up with the term psychoanalysis in 1896. It centered around the idea of an empathetic conversation between therapist and patient. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, there were other doctors in Europe who were experimenting with psychological treatments, including Pierre Janet and Paul Dubois. But it was Freud’s method (requiring his patients to lie on a couch) that became world famous. Freud’s original couch—a present he got in 1890 from one of his patients, Madame Benvenisti—is today kept at the Freud Museum in London.

Freud believed that through the process of psychoanalysis, the patient could make their unconscious thoughts, impulses, and motivations conscious, thus coming to a greater understanding of their own self-awareness and freeing themselves of repression. Psychoanalysis began as a treatment method to try and cure certain mental illnesses. But it gradually evolved into a cultural discipline that tried to explain art, religion, jokes, mythology, politics, anthropology, and literature. Tallis claims Freud was never fully committed to psychoanalysis as a treatment method. Especially towards the end of this life, when the Austrian neurologist became much more focused on cultural-philosophical questions. “Psychoanalysis evolved into an intellectual framework to analyze culture, and it can be viewed as a late offshoot of German Romantic philosophy, which was preoccupied by mysterious nature, universal symbols and the unconscious,” says Tallis.

Over time, psychoanalysis evolved into one of the great intellectual movements of the twentieth century. It was launched almost by accident, though, when Wilhelm Stekel, a fellow Austrian physician and psychologist, suggested to Freud that he should start a discussion group. Freud agreed. In the autumn of 1902, Freud sent post-card invitations to Stekel and three other Viennese physicians, Max Kahane, Rudolf Reitler, and Alfred Adler. At their first meeting, the five men assembled at Freud’s home at 19 Berggasse, in Vienna’s 9th district, to debate the psychological significance of smoking.

Thereafter, the group met every Wednesday evening. They became known as the Psychological Wednesday Society and expanded to around twenty members. The purpose of the Psychological Wednesday Society was to develop and promote a new science. But Tallis claims Freud’s early “devotees were peculiarly willing to embrace ritual and conduct their business in a manner suggestive of esotericism and mystery.”

In April 1908, the group changed its name to the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. “I find it very difficult to imagine psychoanalysis developing anywhere else but Vienna, because of the particular cultural pressures that shaped Freud’s thinking and direction of thought,” says Tallis. He also claims that psychoanalysis never quite divested itself of its cultish qualities. “Freud was always revered as a prophet, and always surrounded by a protective inner circle of initiates.”

In Becoming Freud (2014), the British author and psychotherapist, Adam Phillips claimed the evolution of psychoanalysis was born out of specific cultural conditions, particularly to Jews in nineteenth-century Vienna, who were trying to find meaning in a multi-ethnic empire, where they remained the ultimate outsiders. Freud’s first followers and patients were indeed Jews. But “Freud saw himself first and foremost as a German who was bound to the German language and to Germanic culture,” Tallis explains.

A secular Jewish atheist, Freud detested all forms of religion. In fact, Freud even went as far as banning Jewish observances at home in Vienna. Still, as Tallis points out, many aspects of Kabbalah, the Jewish mystical tradition, presage psychoanalytic thinking—namely dream interpretation, close attention to language, conceptualizing sexual desire as an energy, and the recognition of symbols. Kabbalistic knowledge is usually communicated orally, as is psychoanalysis, which is known as a talking cure. “Freud’s ancestry was Orthodox, and there is some evidence to suggest that Freud owned volumes of Kabbalah,” says Tallis. “In Habsburg Vienna many members of the established middle class found the idea of being examined by a Jewish doctor repulsive, so Freud had to seek out his patient group and his colleagues, within a rather restrictive and almost entirely Jewish environment.”

Freud might have shunned the religious aspects of his Judaism. But he endorsed his Jewish cultural background with great enthusiasm. “You can see that in his writing on Jewish jokes, Freud took humour seriously and recognized that it has a fundamental role in human behaviour,” says Tallis. “Freud also paid attention to the fact that Jewish jokes are a useful defence [mechanism] because many of them have these self-protective antisemitic tropes in them.”

In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), Freud describes the psychological processes and techniques of jokes to the processes and techniques of dreamwork and the unconscious. But are these merely Freud’s opinions? Or can these ideas be quantified and tested against reliable scientific data? Many of Freud’s critics don’t seem to think so.

In 1984, Jeffrey Masson published a damning critique of the Austrian neurologist. His book The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory, claimed psychoanalysis was a pseudoscience based on a fabrication of lies that oppressed women.

Masson is just one of many so-called Freud bashers. Others include Frederick Crews, who published Freud: The Making of an Illusion (2017). Freud bashers have accused Freud of being a child rapist, incestuous, a plagiarist, over-controlling, an unfaithful and tyrannical husband, a liar, a fraud, money-obsessed and ruthlessly ambitious. Conversely, Freud’s most loyal followers and disciples (including his daughter, Anna, and his good friend and biographer, Ernest Jones) have treated his books and ideas like sacred works of scripture, accepting his authority without question or hesitation.

But is it possible to embrace Freud’s core ideas while also remaining critical of him? Tallis believes so. He claims Freud “was unquestionably a great writer, but he is often contradictory, and his ideas are generally not original.”

“Freud was not a reliable reporter, particularly when writing up his case studies, where he overemphasized the importance of sex as an aetiological factor in mental illness. But too much Freud bashing means that we forget everything of interest that is right in Freud’s work,” says Tallis. “There is a commonly held view that Freud is a very significant cultural figure, but his science is very dubious, which is simply untrue.”

This past April, Tallis elaborated on this topic in the scientific journal, Brain. An essay he published there pointed out that neuroscience wasn’t sufficiently advanced in Freud’s time to supply the foundations for what Freud called the psychical apparatus. As neuroscience has advanced into the twenty-first century, though, the scientific community has started to connect cutting-edge research to Freud’s model of the mind. Freud first described this model in an extended essay, The Ego and the Id (1923), which viewed the mind as having three ‘psychic’ structures: the id, the ego, and the super-ego.

Freud claimed the id is the dark, inaccessible part of our personality, whose wishful impulses are assumed to have a genetic, evolutionary basis related to Darwinian objectives. Namely: self-preservation, defence of territory, overcoming rivals, and sexual reproduction. The ego, by contrast, is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world. Or, as Freud put it: “the ego stands for reason and good sense while the id stands for the untamed passions.” Freud claimed that the superego functions as an individual’s self-critical moral conscience. Most individuals tend to learn about the superego in early childhood from parental authority. But in the fullness of time, by exposure to social authority, such as the institutions of law and order.

“Freud’s structural theory of the mind has been much praised by many neuroscientists,” says Tallis. “This is one of the interesting things about Freud, he said things that seemed to be relevant to the present and to the future, because he was always very modern, in terms of his outlook, and yet, he was always looking backwards to classical civilisation.”

The relationship between antiquity, mental states, and metaphor plays an important role in Freud’s writing and thinking. Freud’s love of the ancient world began as a child when he was taught Latin and Greek at school and introduced to classical literature. Freud’s earliest heroes were the military giants, Alexander the Great and Hannibal. One of Freud’s most well-cited ideas, the Oedipus complex (which describes a child’s feelings of desire for their opposite-sex parent and jealousy and anger toward their same-sex parent) is named after the Greek myth of Oedipus, a Theban king who unwittingly killed his father and married his mother.

On December 3, 1897, Freud penned a letter to Wilhelm Fliess (who played an important part in the prehistory of psychoanalysis) discussing a dream he had about his favorite ancient city. “My longing for Rome is deeply neurotic,” Freud wrote to the Berlin-based German otolaryngologist. “It is connected with my high school hero worship of the Semitic Hannibal. And this year in fact I did not reach Rome any more than he did from Lake Trasimeno.”

The idea of Rome as the Eternal City inspired one of Freud’s most memorable metaphors. In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), Freud imagines a fantastical Rome “in which nothing that ever took shape has passed away, and in which all previous phases of development exist beside the most recent.” Tallis calls Civilization and its Discontents an extraordinary analysis of modernity. “The book looks at this idea that as civilization gets more advanced, many people remain deeply unhappy,” Tallis explains. “Freud believed our stone age brains cannot adapt to the speed that civilisation is advancing.”

In our present age of global political uncertainty Civilization and Its Discontents has never seemed more relevant. In one of his footnotes to the book, Freud talks of human beings being “born between urine and faeces.” “We are embodied creatures, and our minds are in closer relation to our bowels and genitals than we care to acknowledge,” Tallis concludes. “We are propelled by primitive impulses, and throughout history we have only just managed to stay ahead of our self-destructive tendencies. Freud begs us to consider the evidence of history: the incursion of the Huns, the Mongol horde, the conquest of Jerusalem by pious crusaders, and the horrors of the Great War. He cites a Latin proverb: Homo homini lupus – Man is wolf to man.”

JP O’Malley is an Irish writer living in Croatia.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!