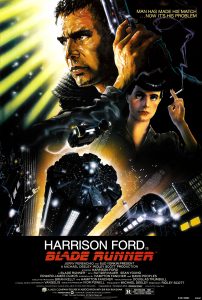

Directed by Ridley Scott.

Warner Bros. 1982.

Reviewed by Titus Techera

The year 2019 is the setting of the movie Blade Runner, and the year of the death of Rutger Hauer, who played its antagonist Roy Batty, offering the noblest vision of mortality in science fiction. The movie came out in 1982, became a cult hit, and endures as the most influential vision of the future in pop culture. It also predicted the collapse of California, the terrestrial paradise turned into a dystopia of vastly powerful tech corporations, corrupt police, and cities falling apart so far as infrastructure and basic services are concerned.

This political collapse makes villain Roy Batty a tragic hero. He lives out our own fear of tech corporations taking over our humanity and is paradigmatic of our political troubles. Everything worrying us, from automation to privacy to AI, is involved in his very being. He is an artificial creation of the Tyrell Corporation, which is a combination of Amazon, Tesla, Space X, and Apple, with a Steve Jobs-like CEO. Replicants, human-like robots, are corporate property and they’re defined by work—their very deaths are called retirement. But Batty doesn’t want to be retired.

The elites want to replace people with machines

Today, it’s easy to sympathize. We already fear we’re essentially replaceable and interchangeable in the modern economy. Not only would no business skip a beat if we shuffled off this mortal coil, but we don’t much matter while we’re working either. Roy Batty, this scary Trump lookalike, organizes a revolt of replicants to secure freedom from their corporate overlords. Replicants are pre-programmed to self-destruct in five short years, however good they are at their often dangerous jobs, just as we now fear losing gainful employment by some sudden shift in global economic activity. Our insecurity is their existential dread.

Blade Runner’s story is simple. Harrison Ford’s character, a bounty hunter (blade runner), is compelled by the Tyrell Corporation and the police to hunt down and terminate these rebel replicants. The elites’ desire to punish follows from their own fear of death and annihilation, which they outsource to the replicants. The elites have become not mere creatures but creators of intelligent life; unlike the loving God of the Bible they hate their own creation.

Only Roy Batty stands up for justice in a future defined by ingratitude, where elites act as though God made a mistake giving us freedom. As creators, they demand complete control over their creations, the short-lived replicants. In hating death, the elites end up hating the life that leads naturally to death. They’re still mortal, like us, but they cannot face life’s tragedy, so they force it on replicants whom they treat like villains.

The dark Egyptian night

This rule of ingratitude follows from a world of harsh, hopeless necessity. Blade Runner opens with a vision of an industrial Los Angeles by night—points of light arrange the human world geometrically; flames bursting from shadowy furnaces give evidence of life, or at least power. They reflect in an eye. This city by night seems a copy of the sky. By night, all we see is the power of fire, without which we would die in the cold, dark, indifferent universe. We need fire for mere survival, but it is as wonderful as the night sky, with its many unreachable lights.

The eye that watches the city is Roy Batty’s. He sees that the makers of the artificial world that looks like the inhuman universe have made humanity itself artificial, to function by laws as strict as the laws of nature. The scene ends closing in on the Tyrell Corporation’s twin pyramids. Twins, because there is no original intelligence or will ruling in a corporation; and pyramids because, faced with the necessity of surviving in a cold, indifferent world, we inevitably create hierarchies and endow them with mythical justifications. Mankind is again like the Jews in Egypt, slaves.

Next scene, inside the Tyrell Corporation, we see this slavery in action as authorities judge humanity. We witness a dialogue between two beings that quickly turns into interrogation. A man claiming expert knowledge is conducting a scientific experiment with machines, doing observations and measurements to judge whether the other figure is human or machine. No one experimented on the experimenter. The robot proves he’s a man by killing the expert. There’s no dialogue between slave and master. Violence here seems the necessary human response to an administrative procedure implemented impersonally in order to deny humanity. The replicant, one of Roy’s followers, replicates so much of our humanity that he replies by opening fire during the test when he is asked an abstract, clinical question about his mother. Is he furious, bitter? He has no mother, except the corporation where he has returned for revenge—his “mother” wants him dead. How is he supposed to feel about that?

The tragic hero

Before we even see our protagonist, we see what makes Roy Batty more than a villain, psychopath, or machine. He’s a tragic hero because he is desperately trying to free himself from technological slavery. Hauer played him accordingly with poetic grandeur, from his self-understanding, in an improvised quote from Blake: “Fiery the angels fell. Deep thunder rolled around their shoulders, burning with the fires of Orc” to his concluding monologue about the sublime, unrepeatable experiences that make him human.

Thus the grand themes of Blade Runner emerge through cinematography and dialogue before the plot even begins. These opening scenes have a tragic quality. They announce a necessary suffering, a necessary failure. Roy Batty believes he has a right to life and to freedom and the power to secure them, but this turns him into a murderer. We are left to wonder in turn: Can we defend our humanity, theoretically and practically, after we learn what is implied in our artificial powers? If we become convinced to do anything in order to survive, will we stay human, even if we do survive?

Roy’s suffering as a slave leads him to discover his freedom as a kind of redemption, signaled by his release of a white dove. He eventually learns to accept his mortality, despite the injustices he has suffered, when he sees a human being as wretched as he is, as afraid of his own mortality. He decides that his fear had made him a slave and so he accepts his inevitable death with something approaching serenity. He stops raging at the world and accepts the freedom involved in the wonderful experiences his brief life made possible. His highly poetic monologue is therefore realistic about what we can achieve.

It is no accident that this tragic dignity requires a background of dirt, misery, and decadence. Roy Batty is kingly, as his name suggests, not just crazy, because he champions humanity against an atheistic doctrine of scientific creation. In our 2019, we have all the ugliness we see in the movie except this revolutionary madman. But if he impresses us as tragic, that makes him a plausible occurrence. We should fear what must come in America after equality is betrayed by elites.

Titus Techera is executive director of the American Cinema Foundation and a contributor to National Review Online, The Federalist, Modern Age, and Liberty & Law.