by Madeleine L’Engle,

edited by Leonard S. Marcus.

Library of America, 2018.

Hardcover, 1917 pages, $80.

Reviewed by Matt Miller

Fantastic literature has always been beloved of those who feel themselves a poor fit with the reigning norms of modernity. This is why J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, for instance, has such an odd reception history, discovered by early hippies and treehuggers in the 1960s yet now embraced by evangelicals and conservative Catholics. By embracing the supernatural, the premodern, and the weird, fantastic authors offer alternatives to disenchanted modernity. The oft-repeated charge that Tolkien offers a simplistic, black-and-white moral world tells us more about the critics than the book, thereby signaling its divergence from modern individualistic moral norms. This antimodern streak appears not just in the works of Catholic authors like Tolkien or Gene Wolfe, but even in writers embracing less conventional accounts of the supernatural, such as John Crowley or Susanna Clarke, whose novels deal in quasi-pagan, Dionysian worlds.

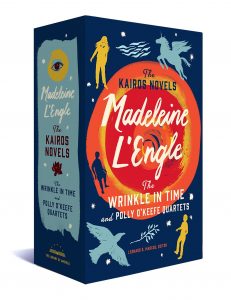

The “Kairos Novels” of Madeleine L’Engle (1918–2007), here collected in beautiful two-volume set by the Library of America, might best be described as “supernatural thrillers” (to borrow a term from T. S. Eliot’s analysis of Charles Williams). Among the eight novels in the series readers will find one novel of travel through space (A Wrinkle in Time), three of travel through time (A Swiftly Tilting Planet, Many Waters, An Acceptable Time), two crime thrillers (The Arm of the Starfish, Dragons in the Waters), one story in which characters enter a boy’s body on the molecular level (A Wind in the Door), and one realistic but spiritually inflected coming-of-age novel (A House Like a Lotus). L’Engle thus ranges over science fiction, fantasy, and conventional young adult drama.

Despite the generic diversity of these novels, however, each considers in its own way the interpenetration of the supernatural and the natural. L’Engle’s adolescent characters grapple with spiritual dilemmas like the problem of evil, the challenge of loving the unlovable, the temptation to idolatry, and more. Most famously, A Wrinkle in Time requires L’Engle’s heroine Meg Murry to embrace with love even the demonic intelligence IT that rules the planet of Camazotz through mind control, and has possessed even the consciousness of her younger brother: “If she could give love to IT perhaps it would shrivel up and die, for she was sure that IT could not withstand love” (148–49). Despite the supernatural adventures of the book, the climax of Meg’s story lies within her: she must overcome her own spiritual failings to overcome her alien foe.

Whether or not her characters experience something as overtly supernatural as time or space travel, L’Engle’s concern lies not merely with the social and developmental struggles faced by teenagers, but with their spiritual lives. Just as Meg must learn to love in A Wrinkle in Time and the volumes of the earlier quartet, her daughter Polly O’Keefe must learn forgiveness in the later quartet. The final book, An Acceptable Time, culminates with Polly forgiving the offenses of a young man described as having been “out of [his] mind with self.” A wise elder character tells him, in language echoing Scripture: “Ultimately you will die to this life.” This unapologetically religious stance, along with L’Engle’s willingness to combine genres, kill characters, and quote difficult literature, doubtless accounts for both the enduring success of her works and their initial difficulty in finding a publisher, with A Wrinkle in Time famously having been rejected more than twenty times.

On these matters L’Engle’s Christianity is both overtly present—among L’Engle’s frequent quotations are many drawn from Scripture, the Book of Common Prayer, and Christian mystics—and diffused throughout the imagery and symbol systems of the novels. The Arm of the Starfish, placed as a pivotal book beginning the second volume in this set, reaches its climax with the sacrificial death of a character named Joshua. The dramatic tension of L’Engle’s work comes, then, not so much through material action but through spiritual conflict, conflict indebted to a Christian account of the nature of the universe and the moral life.

In this, L’Engle aligns closely with Tolkien and his associates among the Inklings. Though L’Engle’s works perhaps bear most resemblance to the novels of Williams, she also plainly shares something of a project with Tolkien and C. S. Lewis, for whom myths and fantastic stories were not “lies breathed through silver,” as accounted in Lewis’s autobiography Surprised by Joy, but instead a means of reflecting upon and challenging the moral failings of the age. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength, for instance, openly challenges the supposed rationality of those who would reshape society with scientistic ethics.

Along with all the greatest writers of the fantastic, the Inklings offer an alternative to (if not a dissent from) what Charles Taylor calls the Modern Moral Order: a rational ethic of individual rights governed by moral laws aimed at maximizing temporal happiness. The Modern Moral Order encourages us to evaluate our moral decisions in light of rational calculations about tangible goods and bads—does one’s chosen sexual indulgence, for instance, hurt anyone?—rather than assessing them via transcendent sources, the Tao or the Ten Commandments. The removal of these common sources further drives moral decision-making back to individuals, eroding our common moral language until it’s little more than a veneer over the id, with moral arguments made on the basis of appeals to personal authenticity, “self-care,” or chosen identities.

For all L’Engle’s explicit spirituality, her works show a greater comfort with the Modern Moral Order than one might expect from a writer so often associated with the antimodern Inklings. For all her explicit Christianity, L’Engle also endorses a modern, liberal form of the religion. This is illustrated most infamously in A Wrinkle in Time as the protagonists list those who have made the greatest contributions against the powers of a darkness, a list that begins with Jesus Christ and continues to Leonard da Vinci, Albert Schweitzer, Gandhi, Buddha, and Copernicus. L’Engle features clerics in more than one novel (themselves somewhat non-modern figures by virtue of their role), but their wisdom tends to favor modern dogma, as when Bishop Colubra of An Acceptable Time blandly asserts that “yesterday’s heresy becomes tomorrow’s dogma.”

Ultimately the spiritual values L’Engle aims at tend toward those that are uncontroversial in the Modern Moral Order: A Wrinkle in Time and A Wind in the Door endorse love over hate, Dragons in the Waters challenges greed and environmental destruction, and An Acceptable Time provides a lesson against selfishness. Two novels take up sexuality, and while Many Waters seems to repudiate lust, A House Like a Lotus renders in uncomfortable detail an encounter between its teenage protagonist and a medical student, commenting blandly that love “has to be given”—a lesson on consent long before that topic rose to the front of our national consciousness. On the level of moral vocabulary, then, L’Engle’s work does not challenge the Modern Moral Order, but all too often uncritically accepts its terms.

In contrast with her character’s banal pronouncements about tolerance, kindness, and consent, the traditional Christian language L’Engle weaves throughout these books stands out with all the more clarity. When Bishop Colubra quotes the psalmist—“O Lord, I make my prayer to you in an acceptable time”—or the hymn “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” the strength and richness of the traditional language makes his own modern vocabulary seem facile by contrast. It is no coincidence that the strongest of these eight novels, A Swiftly Tilting Planet, featuring the most vivid and emotionally satisfying characters in the sequence, is structured and saturated with the language of L’Engle’s version of the ancient prayer “St. Patrick’s Breastplate.”

If L’Engle finally lacks the moral and imaginative resources to escape the linguistic confines of the Modern Moral Order, her work nonetheless points young readers to a treasury of richer language, both in classic literature and the hymns and prayers of the ancient Christian church. Maybe, for young readers already fostering a suspicion that the modern project may not be all it claims to be, she can serve as a pointer to these deeper sources of wisdom. A person could do worse.

Matt Miller teaches English at the College of the Ozarks and lives near Reeds Spring, Missouri. He keeps a commonplace blog at matt-miller.org.