by Federico Martínez Roda.

La Esfera de los Libros, S.L., 2012.

Paperback, $41.

Reviewed by Alberto M. Fernandez

Fascism is in the air in Spain. Actual fascists seem hard to find but you wouldn’t know it from the political commentary inside or outside the country. When Spain’s democratic government took action against an illegal coup by Catalan nationalists in 2017, it was the government in Madrid that was tarred with comparisons to the rule of Francisco Franco.

Inside Spain, the country’s successful transition to democracy after the death of Franco is under assault, from the Left. Spain’s constitution, unity, monarchy, flag, and system of checks and balances are under constant pressure from the ruling Socialists (PSOE) and their populist communist (Podemos) and separatist allies. Anyone who disagrees with them risks being labeled a “facha,” a fascist.

One of many dangerous initiatives pushed by the Socialists is a pending radical revision of Spain’s 2007 Historical Memory Law relating to the Spanish Civil War. Of course, “history” and “memory” are two separate things but the 2007 law was more about modern politics than anything else. Statues of Franco came down and streets named after his officials were changed. Monuments to Largo Caballero, “the Spanish Lenin,” and Santiago Carrillo, the veteran Communist connected with the largest single massacre of the Spanish Civil War, at Paracuellos, remained.

But the proposed Orwellian revision to the 2007 law is much worse than the original, criminalizing free speech and empowering a “Truth Commission” to arbitrarily jail, fine and even prevent academics from teaching should they violate the terms of the new historical memory. The historian Stanley Payne acerbically noted that his first works, in the 1960s, were banned by the Franco regime and, if the Socialists get their way, his last works would be suppressed by the authoritarian Left.

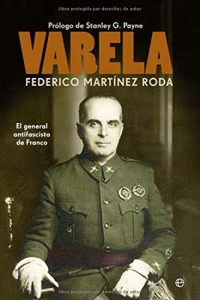

One of many other works that could be suppressed is Professor Federico Martinez Roda’s award-winning 2012 biography of Varela: El general antifascista de Franco. An excellent work that made full use of the extensive Varela Archives in Cadiz, this is the first biography of one of Franco’s most important officers and one of Spain’s most distinguished soldiers. Jose Enrique Varela (1891–1951) was one of only two soldiers to receive Spain’s highest award for valor, the Laureate Cross of San Fernando, twice. The bilaureado Varela was also the only soldier to rise through the ranks from private to Captain General, the highest rank in the Spanish Army.

Born into a family of modest means (his father was a sergeant), Varela made the extremely rare jump from enlisted man to infantry academy cadet to officer. In 1915, he was sent to Morocco where Spain was bogged down in a long and bloody conflict with Muslim rebels. The war was very unpopular and conscript troops were easy pickings for Moroccan tribesmen honed by decades of fighting. Varela was assigned to one of the units, the Regulares, created to ease the pressure of having to use European soldiers. These were units of native soldiers commanded by Spanish officers, a risky assignment. Of the first forty-two officers to serve in the Regulares since their creation in 1911, only seven had not been killed or wounded.

Varela would lead Moroccan soldiers for fourteen years, winning his two Laureate Crosses in small unit actions on the battlefield and rising from Second Lieutenant to Colonel. He became known both for his bravery in battle and for his candor within the military. He bitterly opposed upper class officers who wanted to rely on seniority rather than battlefield promotions for advancement and bluntly told the dictator Primo de Rivera that withdrawal from newly won territory was a mistake. Like Franco, he was an Africanista, one of a corps of Spanish soldiers inured to cruel and tough colonial war. Franco, of course, also fought in the Regulares and later was a leader of the other legendary force of Morocco “expendables,” the Spanish Foreign Legion.

Varela was not initially against the Second Spanish Republic of 1931. He was a friend of a leading Republican politician, Alejandro Lerroux. But Varela was radicalized by the actions of a Republic which seemed to function as a precursor to violent revolution led by Communists and Anarchists, a republic that allowed the burning of over a hundred churches in May 1931 and that violated with impunity its own laws protecting both individuals (such as habeas corpus) and institutions. Rather than the rule of law, he saw a panorama of increasing lawlessness, impunity for leftwing gunmen, and a danger of the army being “sovietized.”

Varela became a plotter against the Republic years before Franco did. Detained on suspicion of participation in the failed coup by General Sanjurjo in 1932, he wrote under a pseudonym the regulations of Spain’s splendid Carlist paramilitary formation, the Requeté. A change in government saw him released from detention and promoted to Brigadier General in 1935 but he was again detained months before the rising of July 1936 that began the Civil War.

During the war, Varela functioned often as Franco’s military “fireman,” taking on the toughest tasks, helping to secure Andalusia for the Nationalist side, breaking the siege of the Alcazar, attacking Madrid, blunting the Republican advance on Brunete and at the Ebro. In 1939, it is “Varelita,” as Franco called him, who places the Laureate Cross on Franco during the victory parade marking the Nationalist victory.

Named Minister of the Army, Varela does everything he can to oppose Spain’s entry into the war on the side of Hitler but he does more than that. He does everything he can to blunt the power of the fascist Falange. In April 1942, he tells Franco that the Falange is corrupt, violent, and out of control and in August of that year he is the subject of a possibly German-inspired assassination attempt by Falangists at a church wedding in Bilbao. Varela angrily calls on Franco to ban the Falange and create a new government. When Franco does not agree, Varela resigns, but upon the public announcement of the resignation, Franco removes senior Falangist leaders from power including his own pro-Nazi brother-in-law who had been Foreign Minister.

The following year Varela is one of a group of key generals who ask Franco to restore the monarchy, an action that the dictator will eventually allow. Varela finally accepts another assignment from Franco, becoming High Commissioner and Army commander in Spanish Morocco from 1945 to 1951. He will have spent more than twenty years of his life, in war and peace, in North Africa.

Martinez Roda does an able job of exploding many of the myths surrounding both Varela and the Franco regime. Varela was not a life-long Carlist nor were Africanistas all crude, unlettered thugs. The Spanish dictator was not a chess player blithely moving pieces on a board but a ruler who interacted with and was influenced by others with their own agency and agendas.

This is a fine biography, real history well told and researched, rather than propagandized and politically skewed “memory.” It is a military and political account that would be of great interest to English-speaking readers.

With the threat of a politically correct and partisan gag rule hanging over the history of the Spanish Civil War, it is the supreme irony that the party in Spain that cannot stop obsessively talking about Franco is the Left. They are also the ones calling for expanding censorship, and noisily take over streets demonstrating against the results of democratic elections, and even have lively ties with foreign dictatorships. Maybe there are totalitarians in Spain after all; we have all just been looking for them in the wrong place.

Alberto M. Fernandez is a retired U.S. diplomat and President of Middle East Broadcasting Networks, Inc.