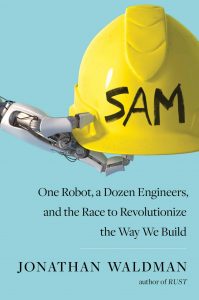

by Jonathan Waldman.

Simon & Schuster, 2020.

Hardcover, 267 pages, $28.

Reviewed by Faith Bottum

If you’re looking for a great tale of entrepreneurial pluck and technological success, Jonathan Waldman’s SAM is not it. In a class that has Tracy Kidder’s 1981 Pulitzer-prize-winning The Soul of a New Machine and maybe Michael Lewis’s 1999 The New New Thing as its valedictorian, Waldman’s account of brick-laying machines is more like the kid who squeaked by with a D in high-school history. Yes, he graduated, but that’s about all you can say. But even though SAM is not convincing as the story of a rising tech start-up, the book will convince every reader that robotics is the next big innovation, the next-gen revolution, the next new tech. Think of this book as the writing on the wall.

SAM tells the story of SAM, the “semi-automated mason,” a bricklaying robot developed by Scott Peters and his father-in-law Nate Posikaminer. Peters was an engineer at General Motors while Posikaminer was a wealthy architect working at a large construction firm. In 2006, Peters quit his job and, with his father-in-law’s encouragement and money, started Construction Robotics in upstate New York.

Over the next few years, the team of engineers assembled by Peters worked to develop a machine that could lay bricks faster than the six hundred bricks a day expected from experienced masons. It wasn’t quite the success they anticipated, demolishing the current construction industry and taking Wall Street by storm. By the end, Construction Robotics had enough of a working model that their robot was bought for a reasonable payday by a large-scale Indiana construction company after being tested without too many hiccups at one of their sites.

The book is broken into two parts. The first half tells about the designing and building of SAM, describing the intricacies of its robotic arms and the difficulties of breaking into the world of construction. Along the way, SAM gives interesting, if somewhat overwrought, summaries of the history of brick from its archaic beginnings to the modern age. Babylon, Egypt, China, Rome: Every great civilization used bricks in its architecture. Durable and easy to produce, bricks stand up to the compressive weight of dead loads, which is why they have proved an efficient building material for thousands of years.

Interestingly, however, the use of brick has been in decline for decades in American construction. The book reports only about 150,000 full-time masons remaining, with an average age of 55. In Jonathan Waldman’s telling, Peters and Posikaminer wanted more than to design the perfect bricklaying robot. They also wanted the world to use their robot to build a lot more with bricks. And why not? The inefficiencies of bricklaying come with the training of masons and the weight they have to lift to increasing heights as they build up a wall. Neither of those slow a robot down. Or, at least, none of them would slow down a bricklaying robot if it had ever been perfected.

Unfortunately, Construction Robotics never quite got that far. The second half of SAM focuses on the challenges of marketing the robot. Peters and his engineering team used the dubious “minimal viable product” business model for tech start-ups, which means that they booked construction gigs before SAM was completely ready, operating according to the theory that consumer feedback would be needed to make the robot better. The book tells story after story of the prototype robot failing because of poor Wi-Fi, unexpectedly curved bricks, and bad weather in trials from Laramie, Wyoming, to Nashville, Tennessee. The masons they encountered along the way proved less than welcoming, expressing their desire to “shove it off the scaffold” and saying that “This is the first bricklaying robot” they’d ever seen and they “hope it’s the last.” It is the contemporary version of the John Henry story of man against machine.

Perhaps one problem with the book is that Jonathan Waldman is not, in fact, an engineer. A graduate of journalism school, Waldman has previously written one other non-fiction book, a semi-bestseller called Rust: The Longest War. He proves a competent writer with natural flow to his prose, but SAM is oddly muddled. Pitched as a tale of entrepreneurship, the book contains almost no talk about money and the business side of things. Kidder’s The Soul of a New Machine, about the race to build a new business computer, in contrast, would be unimaginable without the financial stakes being clear. Lewis’s The New New Thing, about the start-up culture of Silicon Valley in the 1990s, understands clearly the business side of computers. Neither aspiring engineers nor hopeful entrepreneurs will find much to take away from SAM.

Waldman also resorts to some strangely sentimental prose. One of the book’s themes is that clay should be more valued as a building material. And maybe it should, but that’s not going to happen by citing Isaiah and writing lines like “like us, bricks are of the Earth; like us, bricks breathe; and like us, each brick is imperfect but also good enough.” Of the Wyoming project, he writes, “From the start, the job had bad juju.” And when the project looks about to falter, Waldman tells us, “A lot hung in the balance—not just for Scott but for America.”

Still, Jonathan Waldman’s tale of Peters, Posikaminer, and their robotic mason does speak to the dramatic changes that will likely arrive with the next big wave of technology. As it turns out, SAM was not all that great at bricklaying; by the end it did reach 2,945 bricks a day, but the robot had inefficiencies of its own: it proved temperamental and required a large crew’s constant attention. The trouble, of course, was that they were trying to use it in the real world, “where nothing was fixed or level or clean,” instead of the “clear, climate-controlled space” of their upstate New York robotics lab. The future is not here yet, in other words. But it’s coming.

But what then? Construction is the second largest industry in America, employing over 11 million blue-collar workers. Peters speaks of his robotic endeavors in gauzy, moralistic tones, asking us to remember the many workers who will be spared back-breaking labor. He doesn’t seem much concerned with the fact that they may very well be spared pretty much all their labor as a large percentage of them are put out of work. Driverless vehicles are already on a path to disrupt the careers of America’s 3.5 million truck drivers. Robotics in construction will end up taking many more. If you think we have an angry and dissociated working class now, just wait to see what our politics looks like when technology takes away many millions of the jobs they do have. Peters blames the hidebound nature of the construction industry for foolish resistance to his robot, but the workers who saw his clunky prototype were quite wise about the job-destroying future it predicted.

When Boston Robotics releases videos of robots walking like dogs, opening doors, and jumping up on boxes, it can seem that truly functional robots have arrived. The inconclusive results of SAM demonstrate that these machines are not yet ready for anything other than assembly-line production and other narrowly constrained uses. But everything points toward increasing use of robotics. The design of every new car factory, the patent on every new vacuum cleaner, even the telecommuting imposed by the coronavirus shutdowns: Our robotic future is like a ratchet wrench. It only bites in one direction.

Faith Bottum is an undergraduate at the South Dakota School of Mines studying civil engineering. Her work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Commonweal, and other publications.