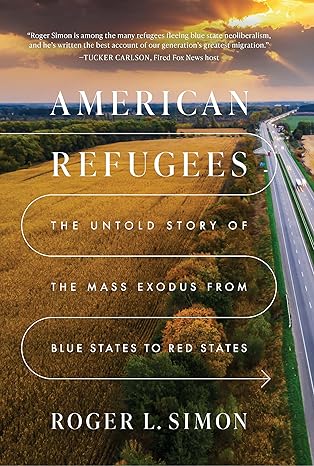

By Roger L. Simon.

Encounter Books, 2024.

Hardcover, 232 pages, $29.99.

Reviewed by Jeffrey Folks.

American Refugees is a worthwhile and highly readable account of an important social trend: the “exodus” of large numbers of people from blue to red states. Its author, Roger L. Simon, is a well-informed and articulate writer who relies on a combination of personal experience and anecdotal evidence in an effort to trace the motivations and backgrounds of a certain segment of these refugees, those of a middle-class background who have relocated from blue states to Tennessee, or more specifically to the Nashville area. In doing so, Simon manages to paint a vivid picture of a class of persons who are deeply disillusioned with the blue states and indeed with America in general and who appear to be seeking the “promised land” in what is, to them, an unfamiliar corner of the American South.

I am sympathetic to Simon’s perspective, but I must emphasize that his approach in American Refugees is far from scholarly. Nowhere do we learn even the most elementary facts regarding the migration: how many have immigrated to the red states and when, which states have lost the greatest number of residents, and why the migrants are moving (the Dust Bowl migration which Simon cites as analogous in some ways was largely one of economic migrants; is the Red State migration economic, political, ideological, or something else?). Also, there is no systematic attempt to survey the opinions of the refugees or even to consult such information where it is available.

Likewise, perhaps because of the author’s reliance on personal experience, American Refugees contains some rather glaring errors. Former governor Philip Bredesen was and still is a Democrat, not a Republican; there is no evidence for the assertion that residents of California and New York exhibit “a considerably higher degree of push” than residents of the red states; one does not have to consume shrimp and grits on a regular basis to be a “southerner” (my wife and I have lived in the South for sixty-five years and never eaten shrimp and grits; neither have many of our friends).

Still, American Refugees is an intelligent, at times passionate narrative of one of the more important tendencies of our times. It displays a good deal of knowledge of regional politics, focusing in particular on central Tennessee, where Simon had lived for four years at the time of writing American Refugees. Indeed, one is tempted to say that Simon knows too much: too many lists of Nashville restaurants and bars; too many names of little-known political figures; too many stories of petty political intrigue. These facts may be important in determining who serves on local councils or who gets elected to the Tennessee legislature, or even, in one case, to Congress, but they do not hint at the more profound differences between red and blue states, including the church-going mentality and moral seriousness that serve as the foundation of southern regional identity.

To my way of thinking, it seems a bit presumptuous to speak with authority about the nature of southern culture while only having lived in the region for a few years. For that reason, perhaps, a number of clichés enter the author’s depiction, including the wealthy songwriter with “a personal gun locker in his house approaching the size of a two-car garage, holding enough weapons…to arm the defense force of a smaller African country. To call this songwriter merely a supporter of the Second Amendment would be an understatement of serious proportions.” Most white southerners do support the right to bear arms, but citing this example seems egregious. Another cliché is the idea that a “slower-moving culture” exists in the South: there was nothing “slow moving” about the mind of William Faulkner or of Flannery O’Connor, nor, I would think, is decision-making particularly slow moving at the headquarters of Coca-Cola in Atlanta or ExxonMobil in Houston. Manners can be deceptive, and it is the responsibility of the cultural critic to look beneath the surface to the true nature of things.

If the cast of its elected leaders is any indication, much of Tennessee still abides by a traditional conservatism which is respectful of the past and suspicious of change, but Roger Simon would seem to have something very different in mind. Instead of a moral conservatism grounded in a set of inherited beliefs, Simon focuses on what must be described as an ideological conservatism reacting to a series of quite contemporary issues such as woke teaching in the schools, DEI policies in corporations and government, increased government spending, urban sprawl, transgender bathroom policies, and the like. Simon himself acknowledges something of this sort when he states that he is “not attempting to write one of those traditional political or social books” but rather, in effect, an account of a newer form of conservatism that actually conflicts with traditionalism in many respects. Thus, there are frequent mentions of times when Simon and his wife, newly arrived from California and originally, in his case, from New York, appear to be uncomfortable in the presence of lifelong southern conservatives. “The refugees,” writes Simon, “found the traditional party system, on the state and county levels, to be somewhere between useless and incompetent, consumed by minor-league matters of self-interest.” Should Simon have been so surprised? Tennessee is a conservative state, but even southern conservatism cannot eliminate the foibles of human nature.

Another aspect of ideological conservatism is its unbending, extreme quality, especially when it comes to an eschatological sense of the “dire straits” that America finds itself in. There is certainly some truth to the charge that progressives are guilty of “suppressing the thoughts and beliefs of others” and even the thought that submission to this control leads “to a new form of totalitarianism,” but the doomsday scenario of ideological conservatives does not, to me anyway, ring true. True enough, America is facing political division and fiscal stress, but I doubt that “virtually every national indicator [is] trending downward” or that Washington is filled with “federal authorities of questionable integrity and even of evil intent.” The suggestion that now, at this moment, we are facing challenges of unprecedented proportions should raise suspicion. It has always been doomsday in America, from Valley Forge to Gettysburg to World War II to the Cuban missile crisis, but America has survived just fine even with what many of the author’s friends view as the excessively moderate tenor of Tennessee politics—with the suggestion that former Governor Bill Haslam was a RINO and that Senator Marsha Blackburn may lean a bit too far left as well. Just how far right do Simon’s political refugees wish to go?

Certainly, American Refugees is a thoughtful and thought-provoking book. It is not a broad account of regional migration but largely the account of the initial experience of one “refugee” from California to Nashville. It rarely ranges outside the metro-Nashville area and thus has little to say about what might be regarded as the quintessential conservative life of small-town and rural Tennessee.

A crucial question within Simon’s book is whether the blue to red state migration will have a transformative effect on American society in general. Indeed, the regional migration may add a number of congressional seats to red states and subtract a few from blue states. Increasingly, corporate headquarters are relocating to safer and more livable cities in the South, and with this relocation comes economic power. And southern universities such as Duke and Vanderbilt are gaining ground on the Ivy League in terms of prestige. Still, with the notable exception of Donald Trump, the cultural and political tendency of American politics has been, regrettably, toward progressive and socialistic policies.

Between 2011 and 2023, six million Americans migrated from blue to red states (a figure not cited in Simon’s book), but not all of those individuals are conservatives and few, I suspect, are what one would call “traditional” conservatives. The migration experience that Simon documents is a significant cultural phenomenon (though swamped in numbers and impact by foreign immigration, estimated for the same period at around 13.5 million but possibly much higher), but it is an open question as to what effect this migration will have at the national level.

In the meantime, we have in American Refugees a quite worthwhile and entertaining discussion of the experience of one refugee’s relocation from the most liberal of states to one of the most conservative, though conservative in ways that the author did not entirely anticipate. Simon’s book is well-written and readable, and it should be of interest to many readers concerned with the increasing shift in population from the blue to the red states.

Jeffrey Folks is the author of many books and articles on American culture including Heartland of the Imagination: Conservative Values in American Literature from Poe to O’Connor to Haruf (2011).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!