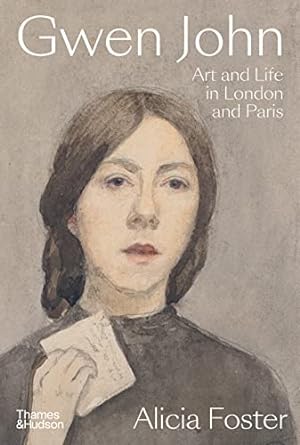

By Alicia Foster.

Thames & Hudson, 2023.

Hardcover, 272 pages, $39.95.

Reviewed by Sean McGlynn.

The work of the Welsh artist Gwen John (1876-1939) has recently re-emerged from relative obscurity. This is due to two fine exhibitions in England in 2023, at Chichester and Bath, and a new book of her life by Alicia Foster, curator of those exhibitions: Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris. Collectively, they offer a welcome appreciation of the delicate and often brilliant paintings of an artist and complex personality who underwent both professional and spiritual trials in her fascinating life, carefully and absorbingly explored in this wonderful book of quiet elevation.

With these events, Gwen John has also emerged from under the shadow of her more famous brother, the artist Augustus John (1878-1961), widely popular at his peak and one of the foremost painters of his time. It can be readily argued that Gwen was the more accomplished and more serious artist of the two. Indeed, Augustus correctly predicted that “fifty years after my death I will be remembered as the brother of Gwen John.” That is currently the case, and it speaks of his sister’s successful blending of formal training with modern sensibilities to engage the viewer with her tranquil yet powerful creations.

Foster is a genial and perceptive guide through John’s professional and personal lives, both being of equal interest. Born in West Wales, John moved to London before she was twenty to attend the Slade School of Fine Art, where two-thirds of her co-students were female and where her potential was recognized by a prize scholarship. An early painting from that time captures her potential. Landscape at Tenby with Figures (c.1896-7) has the town’s bay and buildings glowing in sunlight in the background, while a mother and daughter (it is a safe presumption) dominate a darkened foreground, the young girl looking up to her mother’s downturned face. We do not know for sure if the mother is troubled or merely contemplative; that kind of uncertainty holds through many of John’s enigmatic paintings. It is also a rare exterior: John increasingly focused on interiors as she progressed, something that some, but not Foster, might take for a growing internalization of her own life. “I may never have anything to express except this desire for a more interior life,” declared John.

In 1904 John moved to Paris, settling there six years later. Attending James Abbot Whistler’s elegant atelier, the Académie Carmen, “she wasted no time in moving beyond what she had learned at the Slade. … John would enact what she learned there for the rest of her life.”

Gradual recognition and critical success, not least for her two striking self-portraits of c.1899 and c.1902, did not translate into financial rewards. She took up teaching and, at the age of thirty, modeling, for Auguste Rodin, no less, whom she “revered.” Having dabbled in lesbianism, she now devoted herself entirely to her new love for the great sculptor, while he was at the pinnacle of his fame; it became “one of the most important relationships of Gwen John’s life.” Through Rodin, she slipped into a circle of prominent artists, meeting the likes of Matisse, whom she dismissed as a “snob.” Although she loved Rodin and fully embraced the concomitant sexual adventures, she was but one of Rodin’s mistresses. Her descriptions of him create the image of a spoiled child; she was the only person confident enough to remonstrate with him. Interestingly, Foster believes that John “had a deep need to be in communion with greatness.”

When the relationship with Rodin broke up after nearly a decade, John turned to the apogee of greatness: God. In 1913, after a period of instruction, she converted to Catholicism. She seemed drawn to purgative tribulations: her copy of L’Espirit de Saint François de Sales “falls open most readily at a page about suffering.” Elsewhere, she wrote: “Suffering has always enlarged those who know how to endure it and listen to what it teaches.” “Should I not rejoice in humiliation?” she asks later. “Of course, humiliations are great blessings.” John became close to the convent in her home of Meudon, drawing inspiration from there to create her famous series of portraits of nuns in the later 1910s. Her local priest had to reprimand her for sketching the backs of heads of fellow parishioners in Mass. She pursued religion with the same thirst for distinction she sought for her association with Rodin and her art, saying of the latter: “I must be a saint in my work.”

Despite the importance of her faith, John never quite got the humility part. She repeatedly evaluated her own work as greater than others, even the likes of Seurat and Matisse, and was not reticent in telling that to anyone who would listen. Believing her paintings to be greater and of higher monetary value, she refused to compromise; she was “unwavering in her belief in the significance of her work,” which she believed would be recognized in the future.

A ruthless, selfish streak was apparent, too. Her letters reveal her own concerns over those of others, even despite their personal tragedies. Her lack of compromise—or single-minded devotion to her art—meant that “she had arranged her life purposely to allow her to work in exactly the way she wanted, and she would not—could not—bend.” Her brother Augustus accurately pointed out her “haughty independence.”

John’s art eventually received its most distinguished approbation in the salons of Paris, at a time by which her other famous series, that comprising The Convalescent paintings (late 1910s to early 1920s), was complete. Although exhilarated by the exposure of her work—“the happiest experience of her professional life”—John never exhibited in Paris again after 1925, “a decision that is difficult to make sense of.” Foster suggests that a sudden, uncharacteristic loss of confidence may have prompted this action, but favors as an explanation the fact that John was disqualified when it was discovered she was not French.

Arguably her best work had already been done; her interiors of the late 1900s are perhaps her greatest paintings. They evoke stillness and calm, revealing the influences of Vermeer, Hammershøi and, to some degree, Vuillard. The critic Mary Chamont accurately captured John’s style when reviewing John’s exhibition in London in 1926: “There is certainly no lack of force behind all the softness of Gwen John’s painting.” In her art, John seems to emulate the poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s advice to “evoke an object little by little to reveal a state of the soul.” John possessed that true artistic talent to guide viewers into internalizing her work at a deep level.

She died at Dieppe in September 1939 at the age of sixty-three. Foster suggests that she may have been seeking fresh inspiration there; she may also have been considering a return to Britain at a time when Europe was facing its coming conflagration.

This is an excellent, wholly absorbing book, with a generous supply of John’s paintings to make it a very handsome one, too. If there is one quibble, it is the author’s push to present John as an inspirational feminist figure and one who energetically, almost gregariously, mixed bravely with the men of the art world. There may be something in the former—John moved to Paris and survived there as a single woman, dedicated to her art—but it does seem these days that every female historical figure has to be made into a feminist icon. But this latter reinvention of John as an extrovert is not entirely convincing; she is too enigmatic and complex a character to explain her life so simply. Besides, time and again John extolled the virtues of the solitary, introverted life of the true artist, frequently announcing the idea of her calm collectedness: “I think I will count because I am patient and recueillie [gathered-in, contemplative].” While possessing a steely resolve in her work, socially she was different, referring to her “shyness and timidity… People are like shadows to me and I am like a shadow.” This was an artist who advocated being “reserved, secretive, with a passionate violence that causes suffering.” Solitariness was part of her unbending approach to art. Any involvement in Parisian society can be understood as the necessary socializing required for having her work recognized. Ultimately, though, for John there was no compromise either in art or in life.

The Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris exhibition runs at The Holburne Museum, Bath, UK until April 14.

Sean McGlynn is an historian at Strode College, University of Plymouth. He has written four books and is a regular contributor to The New Criterion, The Spectator, History Today, BBC History and other publications.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!