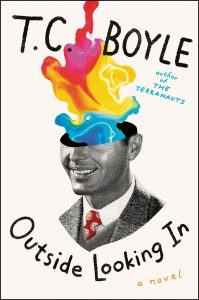

by T. C. Boyle

Ecco, 2019.

Hardcover, 400 pages, $28.

Reviewed by Scott Beauchamp

“Honesty and wisdom are such a delightful pastime, at another person’s expense!”

—Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance

It isn’t too much of a stretch to say that utopian aspirations are woven into the fabric of the American character. They aren’t what makes America particular—other nations and cultures have their own unique flavor of utopian ambition—but the notion that paradise should be easy to enter might be particular to America. It’s the boom town. Fitzgerald’s green light. Kerouac’s ecstatic “it.” In modern Internet parlance we’d call it the “one weird trick.” All your problems, existential and otherwise, will melt away if you just follow this speaker. Or read this one book. Or take this drug. Or join our group. It’s a particularly gnostic notion of perfection, relying as it does on understanding some half-occluded truth to which others don’t have access until they make the plunge and become “one who knows.”

The ur-text for representing the utopian-bent in-group in American literature is Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance, a lightly fictionalized account of Hawthorne’s experiences as a founding member of the infamous farming commune Brook Farm in 1841. In the novel, as in life, all of the lofty and pure aspirations of the commune collapse under the weight of anodyne and petty human nature. Jealous romantic rivalry and self-lacerating desire play a particular role in bringing down the farm. The message is clear: no ideology can completely account for our fallen nature. It’s a lesson Americans would have to learn and relearn over and over again throughout our history. Our reckless honesty mixing with brutal self-deception. Our lofty and abstract aspirations rotten with debased pettiness and jealousy.

The contemporary American writer most attuned to this dynamic and how it echoes through our history is without a doubt T. C. Boyle. So many of his works—most, I would argue—focus on the particular ways in which small groups of Americans delude themselves in to believing they’ve discovered the secret to unlock paradise and the ways in which these fantasies unspool. His most recent work is no different. Outside Looking In is set in the early days of clinical psychological LSD experimentation at Harvard, with the infamous Timothy Leary playing the role of megalomaniacal ringleader. The history of Brook Farm echoes through Cambridge and, later in the book, Leary’s exclusive camp in Millbrook, New York. Only here instead of pietism we have psychology and academia. Instead of farming we have therapy. And instead of God we have LSD.

Outside Looking In, like so many of Boyle’s previous novels, expresses age-defining events within the anodyne context of everyday experience. The book centers around Fitzhugh Loney (quite a name, I know), a Harvard psychology PhD student, and his family as they become wrapped up in the initial excitement of the promise of hallucinogens as a therapeutic tool. Anyone familiar with the real history of Leary’s fall from Ivy League grace will know what comes next. Beginning in the heady and rather innocent days of 1962, moving through the condemnation of the Harvard faculty and administration, a summer and a half in Mexico exploring the potential of ego destruction and group dynamics, to the infamous days ensconced in a mansion in Millbrook, New York. Of course, as the objectives of Leary and his sycophants become more grandiose—dissolution of the individual ego and transformation of humankind into … well, who knows what—the behavior of the group becomes more and more debauched. “Open minds” dissolves into spouse swapping. Marriages dissolve instead of egos. Ancient fears are never quite abandoned, but children are certainly neglected. And so, much as the actual sixties’ social revolution ended in the jaded cynicism of the seventies, Outside Looking In itself traces the decaying effects that moral abandon and intellectual self-deceit have on the Loney family. They become something like a synecdoche for the negative effects the shallow delusions of the Leary-inspired social changes had on American society more generally.

One of the most revealing, and entertaining, parts of the books is when Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters (so scathingly depicted by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test) descend on the group of former academics at their high-end redoubt in Millbrook. If they thought their internal “revolution” was going to stay under their control, a highbrow utopia reserved for the all the right people, the presence of the West Coast pilgrims of chaos marks the beginning of the Ivy Leaguers intimation that they might actually be in control of this thing:

[Fitzhugh] had no use for these people. They weren’t advancing the research. The fact was that they were delegitimizing it with every sunburst of paint they sloshed over the battered fenders of their bus, every shriek of their amped-up music and every frame of film they took.

But as other characters dimly realize (“They’ve got their own Ken, just like us—Ken Babbs”) these younger and wilder bohemians from the West were truly just a more charismatic and more honest reflection of the Millbrook crowd. The pretense to scientific rigor had been abandoned well before the group absconded from Cambridge. Whatever “legitimacy” they were cultivating existed simply in the blissed-out gourds of thrill seekers. The Merry Pranksters had at least done away with the pretense that their hedonistic lifestyle somehow represented an orderly and controlled improvement over the past. They were just in it for the kicks. Leary and Company were still serious about utopia on the cheap.

Leary’s lazy grab at utopia is of course inseparable from his oversized ego. He’s not the protagonist of the novel, but the plot of the book does orbit around him. He stage-manages the movements of his group of academic sycophants, sleeps with everyone’s wives, pressures families to move across the continent, back and forth. Leary, as Boyle understands, is just one iteration of the kind of fevered egos that always seem to accompany American utopian aspirations. They were there at Brook Farm, of course. And Boyle writes about them in many of his other books exploring the theme, most successfully in The Inner Circle (Alfred Kinsey), The Road to Wellville (John Harvey Kellogg), and The Women (Frank Lloyd Wright).

The path of descent always seems the same: initial euphoria fed in large part by the organizing ego behind the project, excitement at the sensation of the new, the project becoming mired in rapaciousness and lust, and once-lofty ambitions fizzling out into a cheap tedium. Think of that decline as it relates to LSD. What began as a dream of kicking down the doors of consciousness eventually became a line of retreat from moral obligations before mellowing into a method of serving your employer more efficiently through “microdosing.” The fact is that LSD was only ever going to be as revolutionary as the moral seriousness of its adherents. The only true revolution is the one that’s ongoing and eternal: cultivating the strength and clarity to pursue wisdom and live our lives accordingly.

Boyle’s book is smart. It seems aware of the internal fault lines running through Leary’s project and communicates them without seeming overly tedious or patronizing. If the book could be said to have a weakness, it’s that the action, as exciting as it may careen forward, seems sometimes to take place in two dimensions. It occasionally has a puppet-show feel. It doesn’t help that the characters, who are supposed to be clinically trained psychologists, don’t seem to speak or think through the lens of their profession. Boyle doesn’t need to go as far as William Gaddis and write entire novels in the professional jargon of the subject, but it would be nice to have gotten some understanding of the professional framework through which the characters deluded themselves. It would have been interesting to think about LSD the way psychologists did.

It might be an odd comparison, but Boyle in some ways stands next to French author Michel Houellebecq. Both cast a cold and cynical eye through the illusions that we not only convince ourselves of, but pride ourselves in believing. And much like Houellebecq, Boyle doesn’t actually make the case for anything. He peers through the cheapness, but doesn’t seem to sense anything beyond that should take its place. Fittingly, Outside Looking In ends with Leary saying to Fitzhugh, “Fuck God … let’s get high.”

Perhaps suspecting that nothing lies beyond the swindle is also part of the American psyche. Or, perhaps it’s just another part of the swindle. Whatever the answer might be, Boyle is here to remind us that it won’t come easy.

Scott Beauchamp is a writer and infantry veteran whose previous work has appeared in the Paris Review, The American Conservative, and Bookforum, among other places. He lives in Maine.