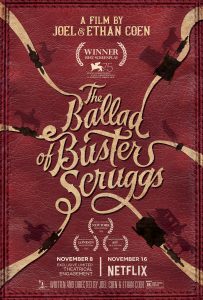

Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen.

Annapurna Pictures, 2018.

Reviewed by Titus Techera

The most interesting thing on Netflix now is the new Coen Brothers movie, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a Western in six episodes, starting with gunfighters and ending with a group of travelers on a stagecoach, with other typical subjects in between: bank robbers (James Franco), gold miners (the great Tom Waits), and a wagon train (the Oregon Trail). It is their first digital film and the first not to be released widely in theaters. Thirty-four years after their debut, about the time they should be considering their legacy, they seem to be embracing the future.

This partnership should work. The Coens are the most prestigious directors Netflix has yet hired. They have everything one could want: a reputation for intelligent movie-making, several Oscars and even more nominations, and a built-in audience. An atheistic willingness to confront the questions of evil and violence and nihilism should be an added bonus—they’re everything sophisticated liberalism could admire.

But only people who, like me, already like the absurd scenes the Coens are famous for will enjoy Buster Scruggs, and it takes at least two viewings to understand anything about the movie. Worse still, it seems to be primarily intended for people who know their way around the Western as a genre, but that’s TCM’s audience far more than Netflix’s. The overlap between fans of John Wayne and The Big Lebowski is probably small.

Netflix needs this caliber of talent to meet its stated goal of becoming the future of entertainment for adults and offering sophisticated, artistically demanding works. But the problem with talent is that you cannot control it. You never know when directors or writers will take the opportunity to offer something perplexing when you only wanted something delightful. It’s true, the audience for Netflix Originals does to some extent delight in perplexity and all sorts of unusual states of mind, but it’s a small audience. Netflix won’t even say how many of their total views actually go to their own productions, as opposed to reruns of Friends.… Cultivating more elite taste is far harder than getting nominations at silly award shows—you’d have to persuade many millions of people, as well as young talent, to admire and imitate the Coens.

For now let’s hope for the best and let’s see what’s good about The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. To begin with, it’s an anthology movie, the stories loosely tied together as a history of the Old West. This is good news. The Coens have talked about how they hope to bring back the anthology as a genre and we can only hope they succeed. The episodic character and thematic or stylistic coherence of this mode would work well in our new era of streaming content.

Anthologies would also be great for the business—creating higher quality content while minimizing risk. Anthologies provide an opportunity for new talent to prove itself without risking significant time and money, and thus without creating crippling pressure. They also can allow proven talent to take a break from grand projects and do something smaller and perhaps more fun.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is not just fun for the Coens. It is a serious criticism of American history and the American audience, from the point of view of the Western. It resembles one Western above all, How the West Was Won, a 1962 anthology whose episodes were directed by the great John Ford, George Marshall, and Henry Hathaway, from stories written for Life Magazine by James Webb. All the aging stars of Hollywood starred in that film. It was intended to show American nobility and goodness through the struggle to tame the West. You got a sense watching it, aside from a certain nostalgia, that the encounter with the wilderness of the great continent brought out the best in Americans. Evil was not concealed or tamed, but it was not daunting.

The Coens don’t share that opinion. They eschew stars and big subjects such as the original’s “Civil War” episode, a double portrait of Generals Sherman and Grant. It is poetry itself rather than its immortalizing of history that interests the Coens: the movies themselves and how Hollywood glorified America. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs opens in Monument Valley and its closing episode is set on a stagecoach: both details recall John Ford and his first great Western, Stagecoach. Moreover, there is a shocking and joking scene, where a woman commits suicide in terror of what Indians would do to her, in the Oregon Trail episode, opposing nature and morality. This rewrites a similar brief episode from Ford’s Stagecoach.

None of this is accidental. The Coens have made genre movies before and we should know what to expect by now from their penchant for absurd comedy. They have a remarkably intelligent way of rehearsing Hollywood history and rethinking it along the way, as a commentary on America. Someone who admires them without losing clarity of mind could map out American history through their work. To begin with, all their movies are set in America. In this case, their theme is Americans’ relationship to violence.

Mostly it’s greed that leads characters in these episodes to kill, or to try to, but in a few cases it’s fear. The reason is not hard to guess. The Coens are implicitly saying that America has been conquered. It’s done. There’s no more frontier! Whatever nobility may be claimed for the old struggle of taming the land, that’s all done. And yet Americans still kill each other for fear and greed; they still love mad killers as a spectacle. Crazy violence is part of the national character—history, to some extent, is just an excuse. You don’t have to agree with them to notice how astute they are, as well as how discreet.

The Coens want you to think about the movie this way, hence the insistence on genre, which they connect to why we watch movies in the first place. The first episode, which gives the movie its title, follows a singing cowboy, Buster Scruggs, through beautifully shot Western scenery that’s just a little off—somehow looking fake, or artificial (a wonderful, surprising job by Bruno Delbonnel, who earned one of his five Oscar nominations shooting the Coens’ Inside Llewyn Davis).

The singing cowboy (played by Tim Blake Nelson, who was even more wonderful in the Coens’ other very musical adventure, O Brother, Where Art Thou?) should remind you of Gene Autry or Roy Rogers. There are indeed musical numbers, but Buster is a thoughtless murderer who takes any slight or provocation as a chance to show off his inventive ways of killing people. He enjoys it to no end and constantly invites us to marvel at him. This is the Coens’ way of pointing out that there’s something inherently wrong in violent genres. People just show up for the violence, since there is no surprise in how things are going to turn out. Without a worthwhile plot, all you have is excuses for violence.

In terms of American history, this would mean that triumphalism kills plot. America can only be America if every thought of “Manifest Destiny” is banished in advance. The suggestion seems to be that, without that banishment, which would mean a revival of tragedy, which would mean poets—like the Coens!—would become famous again, nihilism is inevitable, simply through historical boredom or exhaustion. Success will have crippled America. Put it this way: You can have an America of Henry Fords or John Fords, but ultimately not both.

The Coens have a point here. Instead of revealing human nature or bringing up the possibility of heroism, movie violence tends merely to sate our love of cruelty. Our love of “fail” videos is not that different, and the way we laugh at suffering is simply part of the core of comedy. It may imply as bleak and nihilistic a view as the Coens often seem to espouse. The beautification of violence through drama doesn’t necessarily ennoble it. It might just make it hard, or even impossible, for us to deal with our experience, which is what we should hope to get from reflection on our heroes. There is enough beauty and wit for me to recommend this movie, but I confess I prefer old John Ford Westerns to the Coens’. Looking back on the genre, I cannot help thinking we have lost something, since we can no longer write stories as ambitious as those old movies that tried to define America in a way that allowed for greatness, and even encouraged it.

Titus Techera is executive director of the American Cinema Foundation and a contributor to National Review Online, The Federalist, Modern Age, and Liberty & Law.