By Kevin D. Roberts.

Broadside Books, 2024.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $32.

Reviewed by Daniel Pitt.

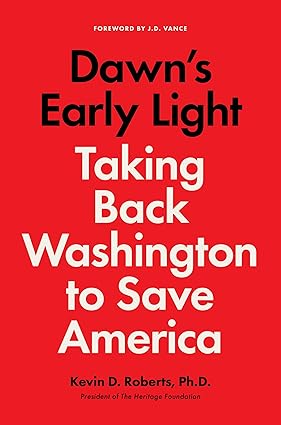

In March 1916, C.S. Lewis, the British Christian apologist, wrote in a letter to one of his closest friends, Arthur Greeves, “When one has read a book, I think there is nothing so nice as discussing it with someone else.” Lewis then added: “even though it sometimes produces rather fierce arguments.” Kevin Roberts’s book Dawn’s Early Light: Taking Back Washington to Save America, with a foreword from J. D. Vance, the vice president-elect, will produce both of these. The book has excellent material to discuss. I’m sure it will also elicit some rather fierce arguments within conservative circles on both sides of the pond. Both men seem aware of this. As Vance writes, “If you’ve read a lot of conservative books or think you have a good sense of the conservative movement, I suspect the pages that follow will be surprising—even jarring.” T. S. Eliot, in his Christianity and Culture: The Idea of a Christian Society and Notes, made the observation that “Conservatism is too often conservation of the wrong things.” Both Vance and Roberts have perceived this too.

Roberts has perceived the deep and fundamental crisis within the American body politic, and that crisis is a spiritual crisis. This deep-seated crisis is also afflicting Britain and the whole of Western Civilization. Conservatives must tackle the root causes of our current cultural malaise, and Roberts, in his book, understands this plainly. Indeed, Russell Kirk wrote that “political problems, at bottom, are religious and moral problems.” Why is this? As Dr. Kirk explains, “Politics moves upward into ethics, and ethics ascends to theology.” Or as Edmund Burke put it, “we know and feel inwardly that religion is the basis of civil society, and the source of all good and all comfort.” Indeed, conservatives who are desirous of fixing family formation, strengthening our civil society organizations, or “little platoons,” or creating striving main streets need to turn to both ethics and theology as well as economics. As Roberts writes, “It’s not enough to identify this or that policy choice. Something deeper has gone terribly wrong. And spiritual problems require spiritual solutions.” This was music to my ears.

Both Vance and Roberts understand and argue for the need for what Vance called “offensive conservatism.” This is not just a reactive conservatism that allows the left to be in the driving seat and “not merely one that tries to prevent the left from doing things we don’t like.” What should conservatives encourage? According to Vance, “We should encourage our kids to get married and have kids.” Vance says we should “teach them that marriage isn’t just a contract, but a sacred—and to the extent possible, lifelong—union.” And we “should discourage them from behaviors that threaten the stability of their families.” Nothing jarring or surprising here. On the contrary, it is desperately needed. Let’s look across the ocean for a moment to Britain. New marriages in 2019 were at their lowest level since 1888. That was the same year Rudyard Kipling published his collection of short stories, Plain Tales from the Hills. Conservatives should endeavour to turn this decline around.

Roberts also argues that conservatives should encourage fighting fire with fire, that schools should teach children piety, that the economy should be shaped to serve the country, that elites should serve the national interest and the permanent things, and advocate for a “family-first fusionism.” The focus of the New Conservative Movement, according to Roberts, ought to be the new legs of “Mom, Dad, and kids” and “the dining room table.” Why is this? According to Roberts, “the greatest threat facing our country today” is “the Uniparty’s war on the American family.” The political left has been at it for years, and the war on the family should worry us profoundly. As Sir Roger Scruton writes in On Human Nature, “the destiny of political order and the destiny of the family are connected.” When the family breaks down, political order crumbles.

Let us zoom in on one of the most important parts of the book. The part on education and piety. Roberts writes, “The single most important thing we can do for education is to ensure that every taxpayer dollar spent on education—federal, state, and local—follows a child to the school of his or her parents’ choice.” I would suggest that parents’ school choice is one of the core policy issues that conservatives need to put front and center of their platform. It is also a policy platform that can unite the conservative movement. Indeed, F .A. Hayek, in The Constitution of Liberty, wrote that “it would now be entirely practicable to defray the costs of general education out of the public purse without maintaining government schools, by giving the parents vouchers covering the cost of education of each child which they could hand over to schools of their choice.” However, the current educational problems are deeper than school choice, even if it is of paramount import. Scruton notes that “it was through culture—through universities, art schools, theatres and books—that the New Left had its greatest and most immediate impact.” Roberts notes, “The reason many parents are having to reassert their rights is that teachers are trying to enforce a truly radical agenda” on their pupils. Because of this enforcement, “[w]e have to restore reality-based education.”

The long march of the Italian Communist Antonio Gramsci through the institutions was a great victory for the left. Roberts points out that this long march has been successful in America’s “public education system, teacher colleges, and universities.” Moreover, these institutions are led by what C. S. Lewis called “the Conditioners.” This type of education has led to “cultureless ciphers who can live anywhere and perform any kind of work without inquiring about its purposes or ends,” as Patrick Deneen observed. Deneen writes, “possessing a culture, a history, an inheritance, a commitment to a place and particular people, specific forms of gratitude and indebtedness…are hindrances and handicaps” from the perspective of woke businesses and educationists. Their luxury belief system sees these fundamentals as old-fashioned and even bigoted, and they need to be expunged from those who are “educated.”

On the contrary to woke educationists, I have long thought that putting dedication to a place, gratitude, and piety back into its central place in education is an essential task of political conservatism. This idea of the centrality of piety is not a new one. The Whig, Lord Brougham, articulated “what is valuable is not new.” In Euthyphro, one of Plato’s early dialogues, Socrates raises the question of piety. Euthyphro’s explanation of piety is “what all the gods love.” As Roberts states in his book, the Roman view of piety is perhaps a more illuminating guide. In our current cultural climate that amplifies the so-called merits of liberal individualism and belittles piety, we have economic instability for the less well-off, which is undermining the family and the social order. For those who cherish individuality, they should remember that we develop our individuality through our social attachments. As these attachments or roots are being slashed, the socio-cultural norms and mores that uphold ordered liberty are being undermined and inhibit the development of individuality and variety. Our current situation in the West, including the U.S., leaves us without order, justice, or freedom, the three core pillars of a successful society.

All this brought G. K. Chesterton’s essay, The Advantages of Having One Leg, to my mind. In this essay, Chesterton writes that “The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.” The things we love and are grateful for in our Western societies are under attack. We might very well lose them, and this realization is animating conservatives like Roberts to advocate for “offensive conservatism” before our fragile civilization is lost.

Dr. Daniel Pitt is a Teaching Associate at the University of Sheffield and a member of the Centre for British Politics at the University of Hull. He is a former graduate student of Sir Roger Scruton and he will be a Summer 2025 Wilbur Fellow at the Russell Kirk Center.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!