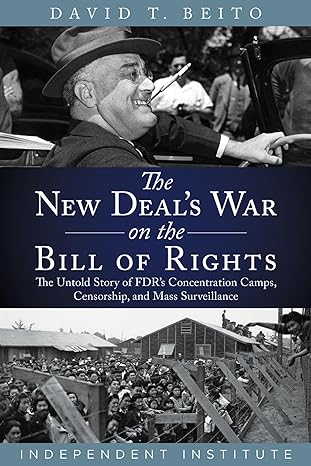

By David T. Beito.

Independent Institute, 2023.

Hardcover, 404 pages, $26.95.

Reviewed by Michael Lucchese.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt ranks highly in historians’ polls about successful presidents. His wartime leadership is often rightly praised, and many see the New Deal as a major accomplishment. FDR remains an icon of liberalism, and presidents from Lyndon Johnson to Joe Biden have sought to imitate him.

In The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights, however, Independent Institute research fellow David Beito exposes the dark side of Roosevelt’s legacy. Far from saving or enhancing liberty, Beito argues that the New Deal built up a vast bureaucratic apparatus which Roosevelt used in near-dictatorial ways to trample on the people’s longstanding rights. The New Deal which emerges from Beito’s narrative is nothing less than a revolution against the American constitutional order.

Beito argues that the Roosevelt administration systematically abused the Bill of Rights, especially the First Amendment. Beyond simply implementing a set of expanded federal economic programs, New Deal Democrats accrued vast bureaucratic powers to silence opposition and persecute political rivals. In Beito’s account, the Roosevelt presidency was not altogether unlike other authoritarian regimes that came to power in the era. Much like fascist or communist parties in Europe, for example, New Dealers used the fear of extremism to persecute their political opponents and shattered long-held First Amendment protections in the process.

The specific constitutional violations Beito cites are both troubling and under-reported in the wider literature. Alabama senator (and later Supreme Court justice) Hugo Black, for instance, used the Internal Revenue Service and Federal Communications Commission to hound opponents of Roosevelt’s agenda. Other bureaucratic allies found ways to use regulations on radio stations to silence or discourage critics. Even at a local level in places such as Memphis, Tennessee, Democratic party machine bosses covered up New Deal corruption and exploited their authority to give themselves unfair advantages in elections.

Perhaps no single group suffered more, though, from Roosevelt’s policies than Japanese Americans. In a moment of wartime paranoia, Roosevelt blatantly disregarded the civil rights of over 120,000 Japanese people, two thirds of whom were U.S. citizens, and sent them to internment camps. Beito does not hold back in his description of the dreadful conditions they faced. He outlines Roosevelt’s genuine racial animus against East Asians, which he describes as “amateur eugenicist views,” and successfully argues that the president was “the man who was chiefly responsible” for these outright tyrannies. Beito even compares the internment camps to the concentration camps established by communist and fascist regimes around the same time.

Japanese internment is among the darkest moments in American history, and Beito does a real service confronting its sordid realities. The United States government did not right these wrongs until President Reagan signed a bill providing restitution to surviving victims, and even today the crimes committed by Roosevelt’s regime are too often forgotten. The episode should serve as a bleak reminder of what happens when the Bill of Rights is thrown out.

New Dealers sometimes justified all this radicalism as a sort of necessary antirevolutionary concession, to prevent the kind of upheaval seen in Europe and elsewhere. But in a speech he gave at Hillsdale College evaluating Roosevelt’s legacy, Russell Kirk said that Depression-era fears of “indignant masses” were severely misplaced. Americans are not a revolutionary people, and even if they sought economic relief, they were uninterested in throwing aside the Constitution or their historic rights to freely speak, assemble, and associate.

The people at large were never enthusiasts for Roosevelt’s most dictatorial actions. Beyond simply chronicling the constitutional affronts of the New Deal, Beito also tracks the emergence of what he describes as a “left-right civil liberties coalition” against the abuse of power. Figures as diverse as socialist Norman Thomas and conservative Michigan senator Arthur Vandenberg roused the opposition and succeeded in stopping some of the worst plans of the New Dealers.

Despite its foes’ best efforts, though, many of the New Deal’s authoritarian and centralizing measures remain in place. The legacy of Japanese internment and radio censorship may be fading, but so much of Roosevelt’s bureaucratic apparatus still threatens Americans’ constitutional liberties. Beito’s work is so important because it can remind readers that these measures were in fact controversial in their day, and that Roosevelt by no means deserves his sterling reputation.

Long before Beito, Whittaker Chambers was one contemporary critic who comprehended the threat Roosevelt’s centralist tendencies posed to American constitutional order. “The New Deal was a genuine revolution,” he wrote in his 1952 memoir Witness, “whose deepest purpose was not simply reform within existing traditions, but a basic change in the social, and, above all, the power relationships within the nation.” He saw the same ideological tendencies in Roosevelt’s liberalism that led to Bolshevism and fascism in Europe, and he tried to warn the American people.

Chambers also understood that the New Deal’s promise of reform brought a host of revolutionary agitators to Washington, D.C. Some, such as his great antagonist Alger Hiss, were formally connected to the Communist Party itself. Others were merely fellow travelers, enamored with leveling ideology, progressive dreams, and Roosevelt’s rhetoric of a world without fear. Whether they preferred a gradual or immediate approach, though, all these revolutionists sought to take advantage of what Chambers called the New Deal’s “shift of power from business to government.”

The New Deal’s “shift of power” was not merely a threat to individual liberty—it sadly hollowed out American community as well. Federal programs began to replace the mediating institutions of civil society. Central planners hubristically believed they could provide more relief for poverty’s ailments than local organizations such as churches, families, or other community groups. Unfortunately, though, Beito wrote his book with a narrow focus on free speech issues for the most part. It is up to other historians—or perhaps Beito in a sequel—to explore the ways New Deal central planning diminished America’s private sphere.

The other real shortcoming of The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights is Beito’s treatment of World War II. He is no doubt correct that much of the era’s propaganda was riddled with hypocrisy, and the Roosevelt administration’s wartime record on civil rights is certainly less than ideal. But Beito is overly sympathetic to the anti-war isolationist movement. Even if some of the administration’s actions to crack down on seditious elements went too far, the federal executive has a real responsibility to root out genuine fifth columnists during wartime.

On the whole, however, Beito’s work is a very welcome change of pace from typical hagiographic accounts of Roosevelt’s long presidency. He proves it was terribly destructive to America’s constitutional order, and more conservatives should recognize the danger of New Deal liberalism. In the past, many neoconservatives used to speak of “making peace with the New Deal.” And in recent years, some among the “postliberals” or “national-conservatives” have argued that the administrative state should be used for conservative social ends. These members of what William F. Buckley once called the “well-fed Right” would do well to read The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights.

The New Deal has been revolutionizing American society for more than ninety years. It is unlikely the programs Roosevelt imposed on the country will ever be completely rolled back. But for conservatives interested in restoring our constitutional order, David Beito’s latest book is an important reminder that we must not simply come to terms with Roosevelt’s revolution.

Michael Lucchese is a Krauthammer Fellow at the Tikvah Fund and the founder of Pipe Creek Consulting.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!