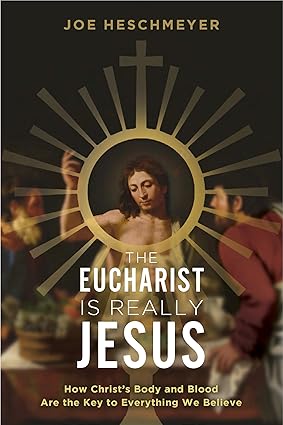

By Joe Heschmeyer.

Catholic Answers Press, 2023.

Paperback, 174 pages, $18.95.

Reviewed by David Weinberger.

C.S. Lewis once observed that he believed in Christianity like he believed in the sun rising. Not only could he see it, but because of it, he could see everything else. With regard to the Eucharist, author and speaker Joe Heschmeyer makes a similar observation. In his new book, The Eucharist Is Really Jesus: How Christ’s Body and Blood Are The Key To Everything We Believe, Heschmeyer argues that understanding the Eucharist is not only critical for its own sake but also for grasping the fullness of Christianity itself.

What, then, is the Eucharist, and why is it fundamental to the Christian faith?

To answer those questions, Heschmeyer examines the Eucharist in its Biblical, theological, philosophical, and historical contexts. “Sometimes,” he notes, “to increase our understanding, we don’t need new information but a new way of thinking about the information that we already have.”

He begins, then, by looking at the New Testament. In the three synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) as well as in Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, Jesus at the Last Supper holds up the bread and wine and tells his disciples to “take, eat; this is my body,” and then, “Drink of it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” These words, often referred to as the “words of institution,” are the basis for understanding the Eucharist as the body and blood of Christ. But how do we know that Jesus meant for his followers to take these words literally and not merely symbolically?

According to Heschmeyer, while Jesus often uses symbols in his teachings—and indeed there is symbolic significance to the Eucharist itself—the words of institution convey something more than mere symbolism. Note, for example, that at other times in the Gospels when listeners are confused about the meaning of Jesus’s words, either Jesus himself or his disciples—to whom, according to Mark 4:34, Jesus privately clarified his public ministry—explain their meaning. Consider, for instance, John 2:18-21: “The Jews then said to Him, ‘What sign do You show us as your authority for doing these things?’ Jesus answered them, ‘Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.’ The Jews then said, ‘It took forty-six years to build this temple, and will You raise it up in three days?’” The Jews, of course, thought that Jesus was referring to the Temple in Jerusalem. John, however, immediately clarifies that “He [Jesus] was speaking of the temple of His body.” Jesus, in other words, was referencing his future death and resurrection, not the literal destruction and rebuilding of the temple. Similarly, in John 4:31-4:34, Jesus’ disciples ask him to eat. He replies that he has food they do not know about. When they express bewilderment at this, Jesus says, “My food is to do the will of the father,” thus clarifying that he is once again speaking figuratively and not literally. Finally, consider the dialogue in John 3 between Jesus and Nicodemus. Jesus explains to Nicodemus that he must be “born anew.” While Nicodemus puzzles over how he can go through physical birth again, Jesus explains that he is talking not about physical birth but about being “born of water and the Spirit,” clarifying once more that he is using symbolism instead of literal language.

When it comes to Eucharistic language at both the Last Supper and in John’s “bread of life” discourse (John 6:22-59), however, things are different. In John 6, for instance, Jesus declares the following to his Jewish critics:

I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live forever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh. The Jews then disputed among themselves, saying, ‘How can this man give us his flesh to eat?’

At this point, Jesus (or John himself) could interject and explain that he is merely speaking figuratively, as he (or John) did in the examples above. Instead, however, he not only does not do that, but he ratchets up the intensity and quadruples down on the literalism of his message:

Truly, truly, I say to you [read: “pay very close attention to that I’m about to say”], unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats me will live because of me. This is the bread which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live forever.”

Thus, concludes Heschmeyer, “Jesus has led his listeners away from taking him simply to mean free food, or manna, or even belief in him, and into taking him to mean that we must somehow eat his flesh and drink his blood.”

Aside from scrutinizing this and other New Testament evidence, Heschmeyer also turns to the Old Testament to show how the Eucharist fulfills the promise of the “old covenant” and thus becomes the heart of the “new covenant.” In the Old Testament, when God revealed himself to the Jewish people, he established a ritualistic framework for cultivating a relationship with Him. This became known as the “old covenant.” Because blood sacrifice was widely used in the ancient Near East to solemnize relationships, the sacrifice of animals (as both atonement for sin and a sign of commitment to God) became the foundation of the old covenant instituted by God. Importantly, however, such sacrifices were viewed as partial and incomplete, thereby pointing toward a future sacrifice that would be complete once and for all.

What all this means for the Eucharist is this: Both in the words of institution and in Jesus’s death on the cross, the perfect sacrifice was realized, which fulfilled the old covenant and established a new one, placing the Eucharist at the center of it. Listen, for example, to Jesus himself at the Last Supper: “Take, eat; this is my body; Drink of it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins (emphasis added).” As Heschmeyer explains, “That’s what holding up his body and blood at the Last Supper means: he’s presenting himself, willingly, to be sacrificed out of love for us.” This, then, is the heart of the new covenant and the key to Christianity itself, which is why Heschmeyer spends several chapters dissecting it.

After exploring this connection, a later section of the book looks at famous saints who have relied on the Eucharist to empower them beyond ordinary human capacity. Consider, for example, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who worked for nearly 50 years in the harrowing slums of Calcutta administering to the poor. “Where an ordinary person might burn out after two weeks,” writes Heschmeyer, “Mother Teresa had something—or rather, Someone—who kept her going in the worst of conditions, from the founding of the Missionaries of Charity in 1950 until her death in 1997.” What was her secret? According to her biographer, Mother Teresa explained,

The Mass is the spiritual food that sustains me. I could not pass a single day or hour in my life without it. In the Eucharist, I see Christ in the appearance of bread. In the slums, I see Christ in the distressing disguise of the poor—in the broken bodies, in the children, in the dying. That is why this work becomes possible.

Moreover, lest one dismiss these words as unserious, Heschmeyer cites a 2014 study in which researchers discovered that having a strong Christian faith does indeed reduce “compassion fatigue,” or the burnout rate for helping those in need. They dubbed it, in fact, “the Mother Teresa Effect.”

But for readers who want to learn more about this and about the Eucharist itself, pick up The Eucharist Is Really Jesus, where one will discover not only the Biblical, theological, philosophical, and historical roots of the Eucharist, but also why it constitutes the summit and source of the Christian life.

David Weinberger formerly worked at a public policy institution. He can be found on X @DWeinberger03.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!