By Anthony Grafton.

Belknap Press, 2023.

Hardcover, 304 pages, $39.95.

Reviewed by Jesse Russell.

“Dame Frances Yates” is a name that usually does not cross the lips of the educated public. However, in the field of Renaissance studies, Yates’s name can generate one of three responses. The first is ignorance of a scholar who is out of place in the twenty-first century postcolonial and race and gender theory discussion. The second response to the mention of Yates is a quick and humorous dismissal of a scholar who got a little too preoccupied with magic and conspiracy. The third response to Yates is admiration for the work of a prolific scholar who chronicled the (re-)emergence of Platonic theurgy (magic that utilizes a Platonic metaphysics), Hermeticism, and (“Christian”) Kabbalah into Western Europe during the 15th century.

Dame Frances Yates (1899-1981) was a prolific Renaissance scholar who associated with the London Warburg Institute, itself founded by the eccentric scion of the Warburg Banking Family, Aby Warburg. Beginning with her work Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964) and continuing with her tomes, The Art of Memory (1966), Astraea: The Imperial Theme in the Sixteenth Century (1972), and The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age (1979), Yates argued that beginning with Renaissance Italian priest, philosopher, and sometimes magus, Marsilio Ficino’s (1433-1499) De vita libri tres or Three Books on Life, the ancient magical teachings of Hermeticism as well as the mystical forms of Platonism were reintroduced to the Latin West. A tradition of “high” magic that utilized Platonism, Hermeticism, and the Kabbalah began with Ficino and continued with other thinkers such as Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), Cornelius Agrippa (1486-1535), Giordano Bruno (1548-1600), and John Dee (1527-1609). These thinkers further diffused their views to a number of European poets, painters, and politicians. In Yates’s reading, the dissemination of Hermetic and mystical Platonic teaching led to Enlightenment science, toleration, and rationalism.

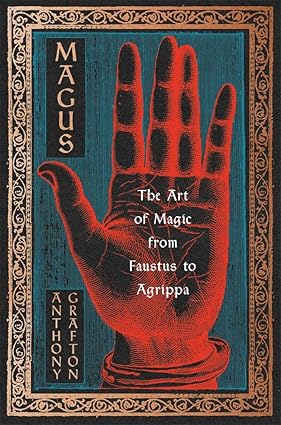

Yates is not the only scholar who has provided this chronicle of the diffusion of Platonic magic and Hermeticism. In 1958, Yates’s fellow Warburg scholar, Donald Pickering Walker, crafted a similar chronology in his magnum opus, Spiritual and Demonic Magic from Ficino to Campanella. Walker provided a similar chronicle of transmitting high magic into the West in this book. Later scholars such as Wayne Shumaker and Paola Zambelli have presented similar chronicles. In his recent work, Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa, Princeton University’s Anthony Grafton provides a chronicle of the development of magic from the infamous Dr. Faustus to the lesser-known but perhaps more influential Cornelius Agrippa, paying close attention to the lives of the various Early Modern magi as well as the historical milieu in which they functioned.

Dr. Faustus is well known to contemporary readers due to Goethe’s famous closet drama of the same name as well as from Christopher Marlowe’s similarly titled play. Dr. Faustus became a work of fiction himself when the fictional Faustbuch (Book of Faust) was published by Augustin Lercheimer in 1587. Despite these exaggerated fictions, Grafton makes the key point that Faustus was recognized by educated and intelligent Early Modern Europeans as an erudite man whose magic literally worked. This is one of Grafton’s central points in Magus: magic was considered a science in the Renaissance. Natural magic or magia naturalis was deemed licit by some Christians under certain conditions. Natural magic, which utilized supposed (pseudo?) Platonic ideas about the interconnectedness of certain things were considered by some to be acceptable. In this (questionable) line of thinking, if one wore a ring with a specific type of stone that had similar Formal (in a Platonic sense) properties to the moon or another planet or star, then one could draw down the power of that celestial body. However, if one involved the notion of a World Soul or the semi-pantheistic idea that the universe was alive, then one voyaged into heresy. Moreover, if one invoked demons, angels, or Platonic daemones, then he or she was meddling in wicked or demonic magic.

Faust, however, made no bones about his explicit practice of demonic magic. The real (or at least one of the real) Dr. Faustus’s was a man named Georg of Helmstadt who studied at the University of Heidelberg in 1483. Faustus journeyed throughout the Holy Roman Empire, proving himself to be a nuisance, claiming to practice astrology as well as conjuring. He was simultaneously known as a powerful magician as well as an alleged criminal. Faust even engaged in advertising and self-promotion, handing out cards with the bombastic claim that he was “the chief of necromancers, an astrologer, the second magus, a reader of palms, a diviner by earth and fire, second in the art of divination by water….” Faust also allegedly claimed that he could restore the works of Plato and Aristotle from memory—indeed, many of the Renaissance magi were or at least claimed to be Renaissance humanists.

Faustus crossed paths with another earlier alleged magus, Benedictine Abbot Johannes Trithemius. Trithemius is a figure who appears in many discussions of Renaissance magic—especially in discussions of Cornelius Agrippa. Trithemius was notorious for his erudition as well as his creation of a system of ciphers or codes, which have been unlocked only recently. As a Benedictine interested in magic, Trithemius is an odd figure who puts to the lie the easy bifurcations between Catholics and Protestants or between allegedly good and bad historical figures. One could be officially a Christian but mix his or her Christianity with (often antithetical) beliefs. Finally, Trithemius’s ciphers do not, in the final analysis, reveal a mysterious message, but rather, in a very postmodern fashion, they simply reveal a method of communicating via ciphers—that’s all.

While the teaching of magic was detailed and diverse, it was also incoherent, and Christian authors often debated the degree to which some types of magic were licit. Pico della Mirandola famously advocated for a “Christian Kabballah” while, at the same time, condemning astrology. Moreover, despite the belief in magic as an erudite science, there was frequently the belief that at least some of these magi were con artists and grifters. Faustus’s contemporary Joachim Camerarius, who was himself knowledgeable of magic and astrology, suggested that Faustus peddled “silly superstitions,” although, at the same time, Camerarius allegedly had made somewhat credulous statements about Faustus’s magic. Moreover, as Grafton further notes, one of the first dissertations on Faust was published in 1693 by Carl Christian Kirchner and was titled On Faust the Charlatan. Grafton’s key point is that Faust and those who followed in his wake exercised a combination of magic and charlatanry as well as erudition and outrageous showmanship, making them not only Early Modern but paradoxically very like the postmodern “magi” of our own time.

Like the Early Modern period, our own age is a time of charlatanry and real evil. A popular meme among practitioners of Wicca is that “we have always been here.” As Christianity has lost much of its political and cultural potency (at least for now), witches, dabblers, and even overt Satanists feel emboldened to flaunt their practice in public. However, what is especially curious is, even among Christians—nay especially among conservative and traditionalist Christians—the advocation of Hermeticism and theurgy combined with Christianity in precisely the same terms and with the same goals as Renaissance magi. At the same time, many figures have appeared on the internet, posing as gurus, healers, wisdom teachers, etc. These figures are Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and New Age. They are liberals and conservatives. They (often) solicit donations, but sometimes they just do it for power and fame. What is humorous (as well as tragic) is that such figures are little different from the legions of quacks that have emerged throughout the centuries, claiming secret knowledge and occult powers. In the end, there is much wise advice in that authentic Christian mystic St. Theresa of Avila: Christians should be guided, not by wild magic from strange characters, but by, as she allegedly said, “prudence and the Gospel.”

Jesse Russell has written for publications such as Catholic World Report, The Claremont Review of Books Digital, and Front Porch Republic.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!