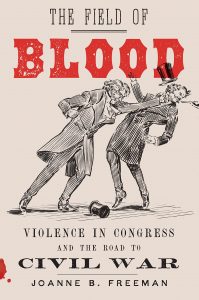

By Joanne B. Freeman.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018.

Hardcover, 480 pages, $28.

Reviewed by John Bicknell

One could make the case that Yale professor Joanne Freeman is obsessed with people getting shot. And we should be grateful. Freeman, who has devoted much of her professional writing to the twin subjects of dueling and Alexander Hamilton, has produced one of the best books of the year, and one of the best histories of antebellum America written in many years.

That’s a lofty statement for a field in which the competition is both deep and wide. But The Field of Blood presents such a holistic examination of the American character in a seemingly micro-venue—Congress in the 1840s and 1850s—that it forces us to reexamine how we’ve understood and interpreted the runup to the Civil War. That is a monumental feat in itself. The fact that she manages to tell a heck of a story in the process puts the lie to the oft-asserted (and sometimes correct) claim that academics can’t write. This is a great book.

The Field of Blood can be seen as a sort of second volume of Freeman’s “Violence in Washington” chronicle. Her Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (2001), explored how politics in the first years after ratification of the Constitution were dominated by the rituals of the culture of honor. Carrying the story decades further into the early republic in her new book, Freeman notes the continuity with the first volume while—like the country itself—taking a turn toward an ever more violent confrontation over the fate of the union.

And she has the perfect narrator to carry the story: Benjamin Brown French, a political lifer from New Hampshire who served for a time as clerk of the House and kept a forty-two-year diary that filled eleven volumes and 3,700 pages. Using French as her guide, Freeman catalogs two decades worth of duels, attacks, and bullying in Congress and on the streets nearby. He provides, in her elegant, lachrymose phrase, “the emotional logic of disunion.”

Freeman’s research is prodigious. But she has done much more than simply compile a vast record. Her mastery of the detail is what gives the story its life. John B. Dawson, a Louisiana Democrat all but lost to history, was a demographically typical lawmaker of his day—college educated, a planter and newspaper publisher, from a well-to-do family, with state legislative experience. He also “routinely wore both a bowie knife and a pistol, and wasn’t shy about using them in the House chamber.” He used each in threatening abolitionist lawmaker Joshua Giddings of Ohio. Dawson was so notorious that Charles Dickens singled him out for notice during his well-chronicled 1842 tour of Washington. These types of detail can yield a metaphorical fist pump (and maybe a real one) from researchers upon discovery, knowing they add a vivid immediacy to the narrative. Freeman’s mining of French’s diary is worth a fist pump or two, as well.

The picture painted by this accumulation of telling detail is like a pointillist painting. As you’re reading, the points pile up in something of a blur. By the time you reach the end and can step back to take in the whole thing, you see the masterpiece. But the result is more disturbing Michael Creese skull than charming calmness of a Sunday in the park with George.

She begins with the notorious Cilley-Graves affair in 1838, in which Rep. William Graves of Kentucky killed Rep. Jonathan Cilley of Maine in a duel, even though the men had no particular argument with each other. A newspaper editor unhappy with Cilley, who had accused the journalist of bribery, had asked Graves to deliver a challenge to the Maine man. When Cilley refused to accept the missive from Graves, the Kentuckian considered it an insult to his honor worthy of a challenge. Graves would shoot Cilley dead in a duel fought just across the Maryland state line from the District of Columbia. From there Freeman steers the reader through nearly twenty years of threats, intimidation, fisticuffs, knife play, and gun play, reaching a crescendo with the infamous attack on Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner in May 1856 at the hands of South Carolina Rep. Preston Brooks, who argued that he was defending the honor—there’s that word again—of his kinsman, Sen. Andrew Butler, whom Sumner had viciously mocked in his two-day “Crime Against Kansas” speech.

The attack on Sumner was a turning point for the country and the nascent Republican Party more than it was for Congress. Invoking “Bleeding Sumner” proved the most effective tool in building Republican loyalty as the party tried to get up and running for the 1856 presidential contest, even as the capital remained obsessed—as Sumner had been—with the confrontation between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers in Kansas. In official Washington, Bloody Kansas had more purchase; in the country, Bloody Sumner stirred the masses. Southerners were firmly behind Brooks and believed Sumner got what was coming to him. Northerners were incensed with Brooks and wanted palpable revenge. The fighting in Congress, Freeman argues, was not haphazard, but purposeful. “When literal push came to literal shove,” she writes, “the voting public wanted their congressmen to fight for their rights at this moment of crisis.”

The figure of a beaten Charles Sumner made Southern violence real to Northern voters in a way that violence in far-off Kansas did not. The split in perception between court and country also may have reflected the realities of antebellum Washington, where Northerners and Southerners worked side by side, drank together, ate together, and sometimes lived together in the same rooming houses. Congress was not, Freeman writes, “in a constant state of chaos; it was a working institution that got things done.” But the bonhomie had its limits, and “the fighting was common enough to seem routine, and it mattered.” In contrast to Rachel Shelden’s argument in Washington Brotherhood: Politics, Social Life, and the Coming of the Civil War (2013), which stressed the personally friendly relations among politically warring members of Congress, Freeman’s story seethes with Northern resentment. Both observe, however, that the Capitol was awash in booze and that the Congressional Globe, the Congressional Record of its day, told only part of the story about what was happening in Congress. “The Congressional Globe makes it seem calm and orderly,” she writes of the House floor, “with a smattering of sniping and scattered interruptions, but in truth the chamber was a roiling sea of noise and motion.”

That seething resentment was a long time in building, and it’s not like no one noticed along the way. In one of his first major public addresses, delivered to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, in January 1838, less than three months after a mob had murdered Illinois newspaper publisher Elijah P. Lovejoy and tossed his printing press into the Mississippi River, Abraham Lincoln warned that “by the operation of this mobocratic spirit, which all must admit is now abroad in the land, the strongest bulwark of any Government, and particularly of those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed.”

Recent incidents involving physical confrontations and assaults on Republican politicians and mail bombs targeting prominent Democrats have raised questions of whether we again are seeing a mobocratic spirit abroad in the land.

Minor celebrities cracking jokes and asking, “Where’s John Wilkes Booth when you need him,” however distasteful, are not in the same league as the shooting of a congressman, the attempted stabbing of a congressional candidate, and the attempted bombing of a former president. We can take some comfort in knowing that members of Congress haven’t started in on one another on the floor of the House and Senate—at least not yet. But, Freeman writes, just the “threat of violence had an enormous impact on congressional debate.”

As we stare into an uncertain future, it’s worth taking into account the crucial inflection point noted by Freeman. Fed up with slave power bullying and imbued with a new spirit following victory in the election of 1854, she writes of “the most dramatic innovation in congressional violence after 1855: Northerners fought back.”

Freeman mostly avoids direct parallels to contemporary politics and emphasizes the vast cultural differences that separate us from the 1850s. But she offers a sanguine warning nonetheless. “The lessons of their time ring true today: when trust in the People’s Branch shatters, part of the national ‘we’ falls away.”

John Bicknell is the author of Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856 and America 1844: Religious Fervor, Westward Expansion and the Presidential Election that Transformed the Nation.