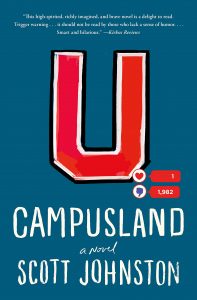

by Scott Johnston.

St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Hardcover, 322 pages, $28.

Reviewed by Matthew Stewart

Would the president of an elite university cave in to the demands of campus militants to the tune of $50 million in order to buy temporary peace? In case four years of nonstop reports of campus cancel culture have blurred your memory, here is a reminder: Peter Salovey, President of Yale, did just that in 2015, promising to plump up minority faculty hiring and to throw lots more money at already existing minority-oriented programs.

Or maybe the question has become not whether but how quickly will college administrators cave? Milton Strauss, president of fictional Devon University reaches his limit in a few days, promising— you guessed it—$50 million for—right again—minority faculty hiring and minority student programming. In Scott Johnston’s satirical first novel Campusland, Devon (located in the small Connecticut city of Havenport) is a thinly disguised version of the author’s alma mater, Yale.

Johnston may have graduated when they still showed music on MTV, and he has never worked in higher education, but this sure-handed and entertaining satire not only has its fingers on the pulse of contemporary academe, it has taken its X-rays and done the lab work to see just what ails it. At the top, a burgeoning administration takes its cues from the corporate world, speaking its vocabulary and pursuing its aims. A super-wealthy (and non-taxpaying) institution focuses on expansion and “upgrading” its brand. The student body is comprised of a mix of grade-hungry achievers, boorish fraternity boys, academic status seekers, and others (“the silent majority”?), but a vocal and determined set of social justice warriors sets the tone. Indeed, the children seem to be in charge while the professoriate and administration is either on board with Social Justice culture or running scared of its warriors.

The main character is the hapless and soon-beleaguered Ephraim Russell, a professor of nineteenth-century American literature. Raised as a working-class Southerner, Russell worked his way through the academic ranks without the benefit of anything a sensible person could call privilege. He seized a propitious moment and managed to get hired at Devon, and to do his job well. He faces his tenure-decision year as the novel unfolds.

Devon epitomizes professional fulfillment and personal contentment for Russell. That is, until he is targeted by student radicals in search of a soft target for their manufactured outrage. Someone must be found guilty of something! What else are college years for other than to cultivate conspicuous compassion and parade one’s elaborately fine-tuned insights into the unquestionable righteousness of victimhood? What better cause than racism, and why not Russell, whose syllabus contains too many white men? Besides he has already bruised the sensitivities of a student by respectfully deflecting her attempts to hijack class time with the endless SJW struggle sessions that she wants to conduct upon him.

The radicals fabricate an ugly classroom disruption, crying racism and pretending that students are being triggered by the study of Huckleberry Finn. (Campus protest as pure performance is well-understood by the author.) They send a doctored video of the event into the social media world, get the student newspaper to “report” on the incident, hang signs on campus, and note with glee the spread of bad publicity growing under the spurious hashtag #DevonShame.

Enter Martika Malik-Adams, Vice President of Diversity and Inclusion, highly paid commissar of wokeness, and expert convener of guilty-unless-you-prove-yourself-innocent tribunals. Malik-Adams is the epitome of the racial grievance careerist, whose positive-sounding job title (I am here to promote values we believe in) belies an out-to-get-even method of operation (I am here to smell out the smallest sin, and finding none, I will be happy to invent some).

In a recent case of life imitating art, several high-level administrators at Oberlin College incited heedless student protests and then gunned for retribution when their allegations of racism against a local bakery were proven to be unfounded. The depth of the administrators’ misconduct emerged during a lawsuit successfully launched against the college. The vindictiveness and unreasoning disregard for either the facts or for just procedures in that case are astonishing, as is the eagerness of highly educated, powerfully placed people to destroy innocent townspeople and more circumspect members of the faculty. Is there an #OberlinShame?

Mr. Johnson could not have known the details of the Oberlin case as he composed Campusland, but its echoes and parallels are a few of the many such that he has skillfully woven into his satire. If Campusland does not provide a complete and up-to-date anatomy of academic contentions, it provides a remarkably thorough catalog of the head-scratching and jaw-dropping events taking place on America’s most exclusive campuses.

The novel is not only aware, perceptive, and prescient. It is also highly entertaining, by turns embarrassing, infuriating, and rollicking. David Lodge’s highly successful academic novels of a generation past were gently comical in their insights, Horatian in temper. Though Mr. Johnston is clearly no misanthrope, his satire is more in the vein of Juvenal. It also takes student life into much fuller account than Lodge, and this too seems appropriate for our topsy-turvy age, where the adults in charge of flagship institutions so often suffer themselves to be lessoned by the youth they are there to teach.

Professor Russell faces more than one trial. He is also indicted by Devon’s Title IX guerrillas, who attach their cause to Lulu Harris, the narcissistic daughter of a one-percenter, whose only real interest is in developing her own personal brand. Lulu is without the least interest in women’s rights, but nonetheless takes inspiration from NYU’s “Mattress Girl,” seeing in her exhibitionism a manner of carving out her own personal brand (that word again).

For her own convenience, she cleverly leads campus feminists to convince themselves that she has been raped by Professor Russell. She plays them with the manipulative instincts of a psychopath: “She boned up on progressive nomenclature … peppering her tweets with words like intersectionality, agency, and transmisogyny, all the while really saying nothing at all.”

The outcomes of these various trials must be left for the reader to discover, as must some delightfully drawn characters in the supporting cast. Scott Johnson is in tune with campus politics. He seems to understand the workings of an elite university from top to bottom. His characterization is apt for comedy; his ear for dialogue, sure in its slight exaggerations; his handling of the plot, deft. Presuming that some self-styled campus radicals might pick up this book, the question is: will they be able to recognize a truly subversive voice?

Matthew Stewart is Associate Professor of Humanities and Rhetoric at Boston University. He has written on war, literature, and the arts as well as on contemporary campus controversies.