By Mark David Hall.

Fidelis Books, 2024.

Paperback, 222 pages, $18.99.

Reviewed by Thomas K. Sarrouf, Jr.

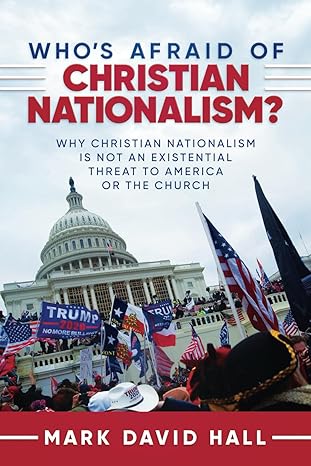

Mark David Hall’s newest book, Who’s Afraid of Christian Nationalism?: Why Christian Nationalism is Not an Existential Threat to America or the Church, could not have been released at a better time.

One of the preeminent religious liberty scholars of our time, Hall’s new book seeks to explain Christian nationalism to a general audience. Partisan media outlets have capitalized on the term’s relative novelty in the public square to frame it negatively, with various outlets calling it a “major threat,” including a viral moment featuring Politico’s Heidi Przybyla calling Christian nationalists an “extremist element of Conservative Christians.” Indeed, an entire organization, “Christians Against Christian Nationalism,” has been created in opposition to the movement. Their statement of values, which they invite all American Christians to sign, states that “[a]s Christians, we must speak in one voice condemning Christian nationalism as a distortion of the gospel of Jesus and a threat to American democracy.” In addition, a documentary featuring Christian leaders across the country, God and Country, was released in February to showcase the threats that Christian nationalism purports to pose to “American democracy.”

Who’s Afraid of Christian Nationalism? seeks to dispel this narrative, which has the prospects of framing the scope and thus the outcome of the upcoming 2024 election. At the same time, Hall is not a Christian nationalist, and sees it as a misguided—though not nefarious—ideology. He ably does the former; the latter, where he details his alternative views on Christian participation in American politics, leaves something to be desired.

The analysis and critiques of Christian nationalism can be categorized as either “polemical” (with the aforementioned goal of “cast[ing] aspersions on conservative Christians who bring their faith into the public square”) or “scholarly.” Hall starts with the polemical works, because, as it turns out, much of the scholarship on Christian nationalism is predicated on the work of the polemical authors. The entire book starts with an anecdote of a reporter asking Hall for a comment about “Christian imagery” used at the January 6 riot. The reporter conveniently ignored his response, which urged against tying the Capitol riot to Christian ideology; instead, the reporter published that Christian nationalists had attacked the Capitol and featured “three photographs containing religious images and words, none of which were from the assault on the Capitol.”

Polemicists, largely journalists and activists, characterize Christian nationalism as a “movement built on a theology that asserts the Christian right to rule” and “support the hegemony of white Christian men over and above the flourishing of others.” Drawing on the theology of Rousas J. Rushdoony, they purport to show that Christian nationalism is the apotheosis of the Religious Right of the 1970s and 1980s. Rushdoony himself advocated for an application of Christianity to all aspects of one’s life, and argued for the necessity of maintaining Old Testament capital punishment laws. However, Hall demonstrates that Rushdoony’s influence was miniscule, and that his followers were few. Claims that Rushdoony was the forefather of Christian nationalist ideology and that his influence was massive is shown to be wildly exaggerated; the claims about him and his supposedly many followers are either hyperbole, unsubstantiated, or outright lies.

In addition to tying Christian nationalism to its intellectual roots in Rushdoony, the polemical literature tries to smear Christian nationalism with the accusation of racism. Hall ties this accusation back to the work of Randall Balmer, who has inspired others to parrot his claim. Rather than being inspired by opposition to Roe v. Wade in 1973, Balmer charges that leaders like Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell mobilized to protect white-only schools like Bob Jones University. Hall ably dismantles this claim, arguing that “[the Religious Right’s] founding members were motivated by numerous concerns, including returning teacher-led prayer to the public school, opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment, banning pornography, restricting abortion, and protecting the independence of religious schools.” As he further points out, racial concerns were probably part of the equation, but the greater inspiration for political organization was a feeling of defensiveness by an encroaching government and secular society. Rather than acknowledge this, Balmer and his students seek to discredit Christian nationalism by tying it to the white racism of its theocratic, Rushdoony-inspired roots in the Religious Right.

However, Christian nationalism is not merely a smear against the credibility and reputation of conservative Christians; it is also a scholarly concept that is the subject of social-science research. Hall reviews this literature, focusing on Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry’s research in Taking America Back for God. Unlike the polemicists, who deal in epithets and distortions, Whitehead and Perry give a definition of Christian nationalism: “an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of American civic life with a particular type of Christian identity and culture” that “includes assumptions of nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, along with divine sanction for authoritarian control and militarism.” According to Whitehead and Perry, 51.9% of Americans fall under this definition either in full or in part, a claim that Hall debunks.

For starters, their questions do not measure what they claim to, which distorts the results. For example, they ask whether respondents agree or disagree with the statement, “The success of the United States is part of God’s plan,” which Hall points out is a doctrine of Calvinism. As he then asks, are all Calvinists Christian nationalists by definition? Moreover, their antipathy towards Christianity and conservative ideals comes out at various points, which is unsurprising given that they praise Andrew Seidel, who is not a scholar and does not pretend to be. The fusion of polemical and scholarly perspective clouds the discussion of Christian nationalism, conflating it with what Hall calls a “toxic stew” of “-isms.”

There are, however, some more carefully created surveys that do capture the attitudes and beliefs of Americans about religion and public life. Hall explains some of the better studies and shows that contrary to Whitehead and Perry’s 51.9% figure, it is more likely that about 21% of Americans could be described as supporting Christian nationalist views (which is also distinct from the “toxic stew” of bigotry). Motivated minorities can wield an outsized influence, but Hall’s research dramatically undermines the scale of the threat.

From there, Hall uses the work of prominent defenders of Christian nationalism to arrive at a definition and compare the critics to the actual views of people who openly advocate for the idea. In looking at the works of Doug Wilson, Andrew Torba, Andrew Isker, and Stephen Wolfe, Hall generously defends these men against undue criticism, shows how they disagree with each other at various points, and explains what they actually think. It is important to note that Wilson, Torba, Isker, and Wolfe are all writing in light of the attacks on Christian nationalism, and engaged in a project of “salvaging the concept,” in the words of Wilson.

Readers might be surprised to find out that these authors are not that interested in “America” writ large, but are more localist in their outlook and ambitions. Hall does not hide problematic or potentially concerning parts of their work, but as is often the case, their more controversial views on hot-button issues are more complicated than the critics show, and Hall takes pains to read their work in the best light. This work is especially commendable given that he disagrees with them, but does so in a reasoned way, one that seeks to “move beyond labeling people and hopefully have a more informed and civil debate about the important issues of our day.”

In Chapter 5, Hall finally gives his definition of Christian nationalism, drawing from both the good survey questions he examined and the actual writings of intelligent defenders of the idea. Christian nationalism

is best understood as the view that the country was founded as a Christian nation and, consequently, that national, state, and local governments should protect and promote Christianity in special ways. Christian nationalists usually believe that other faiths should be tolerated but that the governments do not need to treat all religions equally…. At its core, Christian nationalism involves privileging Christianity above other faiths.

From here, he delves into some of the historical context of Christianity in America’s history, from the Founding to the 1950s and 1960s. He sums up the history by calling American Christian nationalism a “relatively benign phenomenon.” Nonetheless, he opposes Christian nationalism on three grounds: prudential, political, and Christian.

The prudential and the political go together. The Constitution expressly forbids religious favoritism. While various states had religious establishments, Hall contends that the spirit of religious liberty enshrined in the various clauses of the Constitution (establishment, free exercise, “oaths and affirmations,” and religious tests) gradually became part of the national zeitgeist, which influenced the moves towards disestablishment before the First Amendment became applied to the states through the “incorporation” doctrine. Thus, one must choose between Christian nationalism and constitutionalism.

As Hall then posits, even if incorporation was done away with and establishment was licit, it would still be imprudent because of the struggle for political supremacy between different religious groups; Hall also stresses how this tendency would be exacerbated by the increased diversity of the country.

Hall’s religious case against Christian nationalism is that the principles of religious liberty and equality are inspired by Christianity. Because all are created in the imago Dei, each human being possesses dignity, which changes the scope of “who counts” in politics. Rather than ennobling the fair few capable of genuine excellence, all are to be raised up and protected by society. Thus, equality is a Christian development in political history. This idea is also evident in the fight for racial and gender equality, which Hall praises. Although he opposes Christian nationalism, Christian involvement in politics is commendable.

Indeed, Hall points to the Founding as a good example of Christian involvement and inspiration in politics, while also seeking to secure civil and religious liberty. As a scholar of religious liberty and the Founding (and co-editor of a compendium of primary sources on the theme), Hall is able to cite from myriad texts and authors to demonstrate his case that the Founders, virtually all of them Christian, saw religion and religious liberty as two necessary pillars to undergird the Constitutional project.

However, Hall’s biggest vulnerability to criticism arises here. Where the Founders did give priority to Christianity in various ways, between blasphemy laws, blue laws, religious tests for state officeholders, and state establishments, Hall finds these practices “unfortunate.” While worrying about how religious favoritism in law might offend religious minorities is something to consider seriously, diversity arguments undermine a cohesive society. If the city and the soul are connected, as Russell Kirk affirmed, then what shapes the soul shapes the city, and vice versa, which means that vacating the public square entails transforming society, as is the case in America now. Hall does not advocate for “vacating the public square” in the sense of creating a secular public square, but his preferences for humility and restraint are too capitulatory.

From a Christian perspective, the brotherhood of all people united in the Body of Christ is an important goal. Christian history attests to the important missionary efforts of the Christian religion for the sake of saving souls. While this does not mean forced religion (which Hall and Christian nationalists alike repudiate), it does mean that promotion of religion through both cultural Christianity and legal “nudges.” This is true in an instrumental sense that religion is an “indispensable support” to society and republican self-government, something often stressed by many Founding Fathers, notably in Washington’s Farewell Address. But the goal of saving souls is a good in itself and a calling for every Christian. Thus, having Christian leaders, teaching and promoting religion in public school, and having religious holidays—including Sunday as a religious holiday—are important nudges towards that goal.

Who’s Afraid of Christian Nationalism? is a helpful book for thinking through a prevalent topic, and seeing it more clearly. The non-stop news cycle of the Modern West obscures rather than encourages sober reflection on important matters, and propagandizing is often the goal. Hall’s book is an important prophylactic against the fear mongering about an incipient theocracy looming on the horizon. It also returns to the most essential question for any civilization to answer: What is the proper role of religion in social and political life? Hall draws from an impressive career of scholarship to offer an answer, and whether readers will agree or disagree with his conclusions, readers will benefit from grappling with his clear, reasoned perspective.

Thomas K. Sarrouf, Jr., is the Senior Academic Programs Manager at the Intercollegiate Studies Institute and the Podcast Production Manager of “Conservative Conversations with ISI.”

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!