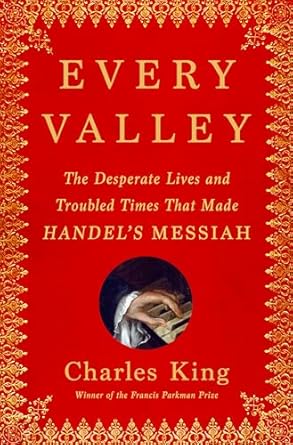

By Charles King.

Doubleday, 2024.

Hardcover, 352 pages, $32.00.

Reviewed by Rev. Dr. Karl C. Schaffenburg.

Joyeuses Fêtes! as a seasonal greeting is no more silly than “Happy Holidays!”, but the fact that we don’t generally encounter this secular greeting in Christian drag in French makes it seem so. Imagine, for example, if at the recent reopening of the great Cathedral de Notre Dame in Paris, rather than simply banal vestments we had had to tolerate a banner about the “season.” But to imagine such a thing is no more than to recognize that as the wider culture that used to be called Western Civilization disintegrates, and as those who are more than ready to attack the Jewish and Christian roots of this civilization now sometimes lament the effects of disintegration, reclaiming what is lost will require work that far exceeds window-dressing. This past Spring, Richard Dawkins, the British biologist best known for his aggressive promotion (e.g., in his 2006 book The God Delusion) of what became known as the New Atheism was interviewed on BBC and essentially argued that the trappings of traditional culture in Britain necessitated a certain tolerance of Christianity, even if he made it clear that this did not extend to belief in God. Which of course raises the question: If God is not central to the idea of Christianity, then what is?

And that’s the question that can be posed about the new book from Charles King, Every Valley: The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times That Made Handel’s Messiah. King, a best-selling author and prior finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and winner of the Francis Parkman Prize in American History, is a professor of International Studies at Georgetown University whose prior work includes at least seven books, mainly concentrated in histories of Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, but with a breakout book in his 2019 Gods of the Upper Air: How a Circle of Renegade Anthropologists Reinvented Race, Sex, and Gender in the Twentieth Century. In posing the question about the role of God in Christianity, I am therefore very much aware of Dr. King’s intellectual accomplishments and abilities, and also recognize that in his new Messiah book he is scrupulously respectful of belief. But to be respectful of faith is not the same thing as to understand it (let alone practice it), any more than decorating a Gothic cathedral with a Happy Holidays! sign would be (in any language).

To be clear, Every Valley is a cracking good read, and tells the stories of individuals that one can take a real interest in. But to tell the story of the unusual circumstances and influences giving rise to Handel’s religious oratorio while ignoring that the purpose of the great work is to testify to faith in God in Jesus Christ is analogous to writing a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. and using examples of his use of Scripture to illustrate only his political savvy, and not also what he actually believed in as a Christian minister.

King’s book is enjoyable because he plays with all of the cultural forces at work in eighteenth century England, and weaves his examination of these factors together with the often engaging details of the lives of the many players involved in what became Messiah. And the overlaps are not trivial. For example, the alto involved both in the Dublin and London premieres of Handel’s work, “Mrs. Cibber,” had a life of such public tragedy that her singing of “I know that my Redeemer liveth” brought tears. But in all his portrait of the very fractured nature of the milieu which gave rise to Messiah, King never engages in the reality that the librettist, Charles Jennens, and composer, Handel, were offering a work that had a very specific message of faith. And the faith on offer was not that as humans we can somehow muddle through when all is against us. It was faith in God in Jesus Christ. Indeed, if we can point to a musical work that does very much portray the cultural milieu surrounding the origins of Messiah it would be the twentieth century opera of Igor Stravinsky, The Rake’s Progress (1951). One cannot listen to the “Roaring Boys” chorus in Stravinsky’s Rake (the libretto is by the great W. H. Auden, rendered into singable form by Auden’s intimate, Chester Kallman) without gaining a better understanding of what William Hogarth was having so much fun illustrating and lampooning. (King certainly has fun with Hogarth’s illustrations.)

The story of the opera is that of the downfall of Tom Rakewell because of what our current culture would describe as his own “poor choices,” choices made despite the admonishments of those around him and of the constant call to love by his betrothed sweetheart, Anne Trulove. It’s a story of self-destruction, but one told in a manner (until the end) in which both Tom and the audience have a lot of fun. And Tom has fun because he ”knows better” until he ends up in Bedlam.

That’s the culture, and in King’s book he does a very good job of narrating the intersection of culture and lives in a way that makes clear that people are ready for a Redeemer because most of life is broken. Indeed, he seems to emphasize the brokenness and instability of eighteenth century life, with quite a lot of detail supplied, for example, in the story of the slave Diallo, and his remarkable escape and redemption from slavery. Diallo enters the story in part to humanize what it means that people like Jennens and Handel (and most of the rest of their moneyed classes) own shares in the South Sea Company, the principal actor in the Atlantic slave trade. Part of King’s point is certainly that the cultural flourishing found in eighteenth century London is paid for by the dehumanization of others. But the chapters on Diallo—all interesting—come across as very tangential to the story of Messiah, except, perhaps, to the “after story.” How so, particularly when we learn that upon his return to Gambia, Diallo becomes an agent for the South Sea Company in the procuring of slaves? It is because the story of Diallo, and his celebrity in London on the way back to Africa, came together with the very real Christian faith of people to make clear that he, Diallo, and any African, was not an abstraction but a person.

Every Valley, for all its strengths, is a case study in how the language of faith is now so little understood within our wider culture that the author—who is always respectful of faith—can essentially ignore that the focus of Messiah is not that (in words found in the epilogue) “a key to living better is practicing how to believe more,” but in what (Whom) to believe in and in how to practice this belief. King is right to note the words of Charles Jennens’s libretto for Messiah: “take the words of the prophets seriously.” But these words do not call us to rely on our own abilities to be not afraid, to take captivity captive. These words testify to the reality that God triumphs, not human will, however strong and well-meaning.

The final words of the epilogue are the words that begin Messiah: “Comfort ye.” But in the libretto (helpfully supplied by King) the words continue, “Comfort ye, my People, saith your God” (my italics). People may still gather to join community sing-alongs of Messiah. It is routinely programmed before Christmas (although it is essentially an Easter piece). But the reality of Messiah is that the music seeks to evoke the supernatural and not just what Abraham Lincoln so famously described in his first inaugural address as “the better angels of our nature.” Messiah’s frame-of-reference is not human except to the extent it embodies the human response to the divine; it is about faith. What King gives us is the human frame-of-reference.

The question becomes, if we are to practice believing more, what are we to believe in, and how are we to practice this faith? This question is another way of restating the difference between faith and religion. Faith first involves relationship. We trust in God. Faith also involves mental assent to particular propositions about who God is and what His will is for us. For example, what Christians say about God in the Apostles’ Creed or the Nicene Creed involves a series of propositions about how God the Father and Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit relate to each other and to us. But faith must be practiced, and the practice of faith is what we call religion, from the Latin re-ligio (that which ties/binds together again). To say, for example, “I’m spiritual but not religious” just begs the question, “In what spirit(s) do you believe?”

Nowhere in the words of the libretto (all either quotations or paraphrases of Scripture) is there any reference to a triumph of the human spirit or will. The big moments that bring people to their feet (the “Hallelujah chorus”) and/or leave them in tears (“Worthy is the Lamb”) speak repeatedly of God’s glory, not any triumph we may enjoy over the world. Indeed, I would argue that unless we can sing, “Blessing, and Honour, and Glory, and Power be unto Him that sitteth upon the Throne, and unto the Lamb, for ever and ever. Amen.”, then comfort ye has a false, self-referential message.

By all means read Every Valley. But then go ahead and really read the libretto.

The Rev. Dr. Karl C. Schaffenburg is a retired Episcopal priest serving part-time in S. Mississippi, following a prior career as a parish priest in Wisconsin and Mississippi. Prior to becoming clergy, Fr. Schaffenburg worked as an attorney in private practice and the pharmaceutical industry, in general management in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries in the U.S. and Europe, and in corporate intelligence and counterespionage roles.

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!