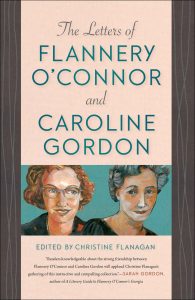

edited by Christine Flanagan.

The University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Hardcover, 254 pages, $32.95

Reviewed by Emina Melonic

“This girl is a real novelist,” said Caroline Gordon in a letter to Robert Fitzgerald. The girl that Gordon spoke of was Flannery O’Connor and this letter to a mutual friend began a correspondence between the two women.

A new collection of letters, edited by Christine Flanagan, is a treasure trove for scholars of both Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964) and Caroline Gordon (1895–1981). At first glance, O’Connor and Gordon would not seem to have that much in common, except that they were both writers. For much of her life, O’Connor battled lupus, which would eventually be the cause of her death at the young age of thirty-nine. She was unmarried and lived with her mother, Regina, on their Georgia farm, Andalusia. Gordon, thirty years O’Connor’s senior, died at the old age of eighty-one, and throughout her life, she too suffered, but in different ways. Even during her life, Gordon was more known as a wife of poet Allen Tate than as a novelist in her own right. Her ailments were mental and spiritual in nature as she battled alcoholism, a mentally unstable daughter, Tate’s frequent infidelities, his own addiction to alcohol, and incredible debt, which Gordon was always mitigating.

And yet, despite the obvious differences (age being one of them), O’Connor and Gordon struck a friendship that was at times filled with happiness and closeness, but also with desperation, frustration, and emotional distance. As Flanagan points out in the introduction, “Gordon’s encouragement could uplift the young writer as her critiques could alienate.”

The collection is divided into five parts, in chronological order up until O’Connor’s death. The final part, “Postscript,” includes letters between Gordon and Robert Giroux dealing mainly with thoughts on how to keep O’Connor’s memory alive. Accompanying the letters are the editor’s occasional biographical notes that place the letters in context. These are placed rather gracefully and diligently and do not intrude on the letters themselves.

The main theme that runs through the letters is the art of creating fiction. From the very beginning, Gordon offers suggestions to O’Connor on how to be a better writer. This is far more than vague musings of an older and more experienced writer who is interested in appearing sagacious without giving solid and grounded advice. On the contrary, one of the first letters Gordon sent to O’Connor was a nine-page, single-spaced critique of O’Connor’s first novel, Wise Blood. Gordon was generous in her comments: she praised O’Connor where the praise was deserved, and offered changes where characters needed to be grounded in real life.

O’Connor’s novels and stories are often populated by “freaks,” and Gordon recognized this immediately. “It is fashionable to write about freaks,” she writes in an early letter. She then goes on to heavily criticize Truman Capote and his superficial freaks on parade that, according to Gordon, are only bound for a clinic. But O’Connor is different and most of all authentic: “You are giving us a terrifying picture of the modern world, so your book is full of freaks. They seem to me, however, normal people who have been maimed or crippled and your main characters, Sabbath, Enoch, and Haze, are all going about their Father’s business, as best they can.”

It certainly is a terrifying image that O’Connor paints for her readers. Terrifying because the characters are free and authentic in their freakishness without wearing it as some kind of affectation. But the truth of this metaphysical state has a darker side: an unpredictability that will unleash itself into the world. But as O’Connor wrote, “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.”

Technical aspects of O’Connor’s work are heavily discussed in Gordon’s letters and for the most part, O’Connor never submitted any stories for publication until she read Gordon’s suggestions. This may seem like an imbalanced relationship and that O’Connor might have been beholden to, or worse, controlled by Gordon. But O’Connor retained her strange sense of humor throughout the correspondence. On one occasion, when Gordon suggested she look to Henry James for some pointers in crafting fiction, O’Connor doesn’t disregard her advice but at the same time, in her typical way of being, doesn’t hold back either: “My method is more likely to be affected by my mother’s dairyman’s wife than Mr. Henry James.” The response reveals the world that O’Connor was part of and that she could not escape no matter how many times she ventured to the East Coast. More than anything, the daily routines of farm life and her mother’s work informed her stories.

Another theme that runs through the letters, directly or indirectly, is the Catholic faith, or more precisely the vocation of a novelist who also happens to be Catholic. Catholicism is a demanding faith, if done right, to use O’Connor’s manner of speaking. It isn’t for the weak-hearted but for the agile because there is nothing comfortable or pleasant about the cross. Of course, O’Connor knew this in the deepest crevices of her own being and dealt with her burdens according to her faith. Gordon, too, suffered greatly, yet neither woman complained about it to the other.

They both rejected a Catholicism devoid of imagination, or what we might call “catholic kitsch.” But the problem of being a Catholic novelist was on their minds. In one of the early letters, O’Connor voiced this concern to Gordon: “I used to be concerned with writing a ‘Catholic’ novel and all that but I think now I was only occupying myself with fancy problems. If you are a Catholic you know so well what you believe, that you can forget about it and get on with the business of making the novel work.” O’Connor did not turn the Catholic faith into an ideology or an -ism, but treated it as a lived reality, a mystery. This is part of the reason, surely, that she has achieved her place in the American literary canon. She didn’t utilize the doctrines of the church and proceed to preach from the pulpit. She wasn’t a false prophet like many of her characters.

As the years passed, O’Connor and Gordon grew slightly apart. There are gaps in their correspondence especially between 1956 and 1957 and 1959 and 1962. Any reader or scholar can only guess as to why this emotional and epistolary distance occurred. One of the Gordon biographers, Ann Waldron, speculated that whenever Gordon didn’t write, it was because her life was unraveling. She rarely wrote to O’Connor about her marital troubles, but she was being torn apart emotionally and mentally by the various forms of abuse she faced from her husband.

On one rare occasion, Gordon revealed to O’Connor (as well as their mutual friends, Brainard and Frances Cheney) just how exhausting life with Tate had been. “For years,” writes Gordon, “his eccentric behaviour was directed mostly at me—very few people knew that there was anything wrong. But now that I play such a small part in his life his eccentricity is becoming common knowledge.” It wasn’t just the psychological eccentricities that were proving to be utterly exhausting for Gordon. Alcoholism, infidelities, and debts converged in a spiritual chaos and the divorce was inevitable.

But it would be unfair to place the mounting distance between the two women all at Gordon’s feet. O’Connor exhibited a certain level of impatience when it came to some of Gordon’s criticisms of her work. Neither woman was a perfectly balanced creature. On the contrary, they come across as deeply human in all their flaws and beauty.

It would be understandable if readers and scholars gravitated to this correspondence looking to learn new things about O’Connor, but it will hopefully also pique an interest in Gordon’s work. These newly published letters are yet another lens through which we can look to catch a glimpse of two wonderful writers. More than anything, what is revealed here is an authenticity of being in both women. They are utterly honest in facing the burden of the cross. For them, to gaze at the suffering Christ brings fear and trembling but also agility of the spirit and more than anything, hope.

Emina Melonic is a writer based in East Aurora, New York. Her work has been published in National Review, The Imaginative Conservative, The New Criterion, New English Review, Law and Liberty, American Greatness, VoegelinView, and Splice Today, among others.