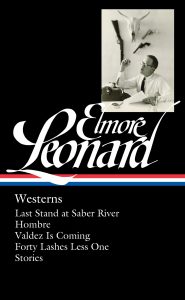

Westerns: Last Stand at Saber River, Hombre, Valdez is Coming, Forty Lashes Less One,

Westerns: Last Stand at Saber River, Hombre, Valdez is Coming, Forty Lashes Less One,

by Elmore Leonard.

Edited by Terrence Rafferty.

Library of America, 2018.

Hardcover, 781 pages, $40.

Reviewed by Will Hoyt

I first got acquainted with Elmore “Dutch” Leonard when, quite by chance, I read the first chapter of Freaky Deaky, his tightly scripted 1987 take-down of acid-dropping, formerly underground, 1968 Democratic National Convention-derived Weathermen who aspire to put still lethal bomb-making skills to new, considerably more lucrative use after recent stints at Milan and Huron Valley Correctional Facilities just south of Ann Arbor. In the first sentence we learn that Detroit Police Sergeant Chris Mankowski, Crime Lab section, has received a call to remove a possibly activated bomb. Second sentence: “What happened, a guy by the name of Booker, a twenty-five-year-old super-dude twice-convicted felon, was in his jacuzzi when the phone rang.” Booker, freshly graduated from street-dealing organizations like “Young Boys Incorporated” and “Pony Down,” calls out to his bodyguard, Juicy Mouth, to pick up the phone but Juicy Mouth is absent so Booker has to answer the phone himself. It’s his girlfriend. Are you sitting down, she asks. “I am,” he says, while determinedly settling into a green leather wingback chair that once belonged to one of Detroit’s automotive pioneers. “I have sat the fuck down.” At which point the girlfriend tells him that by sitting in the chair he has activated a switch that will cause a bomb to go off the instant he stands up.

That kind of opening compels attention, but it isn’t until Booker starts berating his would-be savior one page later that Leonard sets the hook. “‘I been waiting,’ Booker says. ‘You know how long I been waiting on you? I don’t know where anybody’s at. I been calling. You seen Juicy Mouth?’” Who is Juicy Mouth, Chris Mankowski wants to know. “‘Suppose to be guarding my body.’” Who was the woman on the phone? “‘Suppose to be in love with me.’” What’d she tell him? “‘Say I get up, I’m blown up.’” That’s all? “‘Man, that’s final, that’s all there is all, nothing else.’” Yes, but do you believe her, Chris asks. “‘Asshole, you expect me to stand up and find out?’” By the end of that short first chapter, this reader, for one, had committed to finishing the novel.

It turned out to be a big commitment, for upon reading one Leonard novel you tend to want to read another, and it turned out that Leonard had written not just ten or twenty but forty so-called tough guy novels over the course of a career that spanned—this is hard to believe—sixty years. His first novel, The Bounty Hunters, came out in 1953, just four years after Ross MacDonald’s first Lew Archer detective novel, The Moving Target, and three years after pulp fiction veteran John D. MacDonald’s crime fiction debut, The Brass Cupcake. Yet Leonard’s last novel, Raylan, which features the return appearance of a straight-shooting U.S. Marshall from coal country, came out in 2012, a full twenty-five years after the two MacDonald careers had ended.

The quality of Leonard’s production is uneven, and in some of the novels where live-wire zip and zing are absent—works like The Moonshine War (1969), Split Images (1981), Cuba Libre (1998), and Mr. Paradise (2004)—Leonard seems not so much to be writing as going through motions and mechanically repeating moves that had worked for him in the past. But, when Leonard is “on,” as he was during most of the 1980s and 90s, he is really on—so much so that his writing might at those times fairly be described as dazzlingly electric and superior to the work of his peers. Wherefrom the difference?

Part of it is that, unlike the novels of hard-boiled fiction master Raymond Chandler, Leonard’s novels aren’t (ultimately) about the moral ambiguities of crime detection or the pleasures of solving a puzzle. Nor are they (ultimately) about beach bum expertise or access to friends in high places, as in John D. MacDonald’s wonderful private investigator series starring Travis McGee. Trained as Leonard was by writing for pulps like Dime Western, Leonard tends to focus instead on moments of truth that people either rise to or flee from, according to varying degrees of valor, imagination, and moral probity.

Sometimes the main characters in his novels are cops. Other times they are entrepreneurs—think flight attendants who agree to carry cash from an offshore account, or melon-growers trying to beat the weather, or burglars with a business plan, or owners of a company that makes parts for an automotive assembly line. Whatever their line of work, Leonard’s characters are ordinary, if underestimated, and this frees up Leonard to luxuriate, if you will, in what Steinbeck called the “poetry of folks talking,” be they Chickasaw Charlie Hoke (minor league pitcher) reminiscing (in Tishomingo Blues) about striking out Willie McGee in “De-troit” after being sent down to the Mudhens where a pitch that was supposed to curve low and away “bangs letter-high” on a batter; or Harry Arno (bookie) explaining (in Pronto) to a sympathetic cop that FBI operatives couldn’t possibly determine how much he skims before reporting proceeds to Mob-linked silent partners (“Guy calls up, he says, ‘Harry give me the Lions and the Niners twenty times reverse. Bears a nickel. Giants five times, New England ten times if the Rams ten …’ You’re telling me this Bureau guy’s people are going to get a read out of that?”); or Zulu and Snow (“jackboys” working for an arms-dealer) trying (in Rum Punch) to read directions for a rocket launcher they’ve just unpacked so as to fend off a SWAT team approaching their door (“Snow said, ‘Re- … lease. Yeah, it say to release the … something. Release the safe-ty. Yeah, that thing right there. Release it.’ Zulu said, ‘Push it?’ Snow said, ‘Release the motherfucker however you suppose to. I think, yeah, you push it. The next word it say to aim …’”).

But the chief attributes that set Leonard apart are (1) a systematic bias in favor of humor and sunniness as opposed to alienation or cynicism, (2) sustained attention to real-time thinking and what might best be called inwardness ripening to decision, (3) a genius for names, and (4) complete and unadulterated comfort in the company of thieves. Which means: he really is the “Dickens of Detroit” his tombstone claims him to be.

Most of us have read Great Expectations and so can (without too much trouble) recognize these four traits as Dickensian, but where, in Leonard’s case, do the winning qualities come from? Happily, we now have before us in one volume the very works we need to have in view so as to answer such a question, for the traditional Westerns gathered in the final Library of America tribute to Elmore Leonard’s work are books Leonard wrote while he was discerning his gifts as a writer. On the basis of this evidence now conveniently set before us, we can conclude without hesitation that in Leonard’s case the winning qualities derive from three factors. The first is Leonard’s emulation of Hemingway’s prose style. Leonard’s debt to Hemingway explains to a large extent both Leonard’s gift for the sort of plotting that is required if one is to successfully convey instantaneous moments of decision, and Leonard’s orientation toward morning rather than night.

Without another determining factor, though, I’m not sure Leonard’s attempt to describe the way time widens in moments of instantaneous decision would have been successful, and that supplementary factor is Leonard’s experience as a baseball player. (Leonard’s high school classmates nicknamed him Dutch because he aspired to be a pitcher and shared his namesake with Washington Senators knuckleballer Emil “Dutch” Leonard; Elmore was proud enough of this association to get “Dutch” tattooed on his right shoulder in 1946.) You wouldn’t think that a background in baseball could be inferred from a Western, but of course it can, for a gun leaving a holster is not unlike the moment when a pitcher reveals, at the very moment a ball is released, the finger placement that will determine the thrown ball’s course, and I suspect that transposing a batter’s viewpoint so that it can play in a Western gave Leonard the ability to create his signature fifth dimension that permits characters to recognize the arrival of their kairos, their moment of truth.

And the third important factor contributing to Leonard’s artistry? That is Leonard’s grounding in the Baltimore Catechism.

Leonard was born and baptized in New Orleans, before his father relocated to Detroit after securing a job with General Motors, and Elmore went to daily Mass while attending both Blessed Sacrament Elementary and Middle Schools behind the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament in downtown Detroit, and then Jesuit-run University of Detroit High School. After serving in the South Pacific during World War II, Leonard enrolled at the University of Detroit proper to get a B.A. in English. Years later, asked about his training, he said Jesuit instructors had taught him “how to think.” But you don’t need to read Library of America’s handy biography to discern this, instead you can simply read Leonard’s early Westerns, for these books often read, quite literally, like prayer books or catechisms. Acts of contrition and prayers to the Virgin Mary appear regularly as Mexican segundos get into tight spots, and characters like Paul Cable, the Saber River protagonist, systematically think through the difference between self-defense and murder before picking up a gun to defend a homestead. Are these religious accents window dressing? Up until 1957, perhaps they were. Starting in the late 1950s, though, Leonard’s explicitly Catholic emphases deepen to include the anthropological dimension to Christology, and from that point forward his plots get significantly stronger.

The part of the Christian schema that appears to have intrigued Leonard most strongly, starting in 1959, is the doctrinally sound but often unexplored claim that Christ is a new Adam who, thanks to utter reliance on God the Father, lives without fear of death and consequently never lies. What would it be like, Leonard appears to be asking, to live like that? The explicitly Catholic aspect to Leonard’s developing anthropology reaches formal maturity in Touch, the novel about a stigmata-bearing healer that Leonard wrote after quitting alcohol in 1978, but the overall shape of the anthropology is already visible in this new Library of America collection of Westerns. “Ecce homo,” Leonard appears to be saying (in counterpoint to Nietzche!) when (in 1961) he names his novel about outcast John Russell Hombre. Russell, already an outcast because he is the child of an Apache father and a Caucasian mother, is strange for multiple reasons. He is fearless, for one thing. He plays, always, for mortal stakes, and he will not, under any circumstance, allow himself to be unjustly put down or used. At the same time, however, if Russell sees someone else suffering an injustice his default position is to not step in to right things in the wronged individual’s favor, because that would amount to robbing him or her of the chance to fight one’s own battle and so come into one’s own, as a person. If, on the other hand, an individual first shows mettle and then is attacked, Russell will (and does) lay down his own life to ensure that person’s continued freedom. Sounds a little like Socrates and perhaps another figure whose name I can’t quite remember.

Leonard took a break after writing Hombre to solidify finances by writing scripts for Encylopedia Brittanica films, but directly after selling the movie rights to Hombre in 1966, he wrote two other traditional Westerns that advance the anthropological vision mapped out in Hombre—both of which are included in the Library of America volume under consideration here. In Valdez is Coming, a temporarily appointed sheriff named Valdez has the temerity to take his job seriously and question whether a man holed up in a cabin with a rifle is as guilty as self-important land barons want him to be, and when the cornered man dies in a firefight with Valdez that was provoked by rifle shots from one of the land barons’ hired hands, Valdez makes it his mission to secure modest but real sustenance for the cornered man’s Apache widow. Despite an almost literal crucifixion, Valdez of course wins her that sustenance, but that isn’t, in itself, the climactic point of the story. The real climax occurs as the land baron’s men leave his employ, one by one—owing to respect for Valdez’ repeatedly demonstrated fearlessness and the rigorously consistent trustworthiness of his word. And then, in Forty Lashes Less One, the final Western in the new Library of America volume, Leonard sincerely and not ironically references Second Corinthians so as to explain how “strength is made perfect in weakness.” Leonard sets things up so the preaching proper comes from the mouth of a well-meaning fool who takes a leave of absence from a ministerial position at Holy Word Church to fill in as warden at Yuma Territorial Prison in southern Arizona, but of course fools in most theatrical productions do turn out to be wise, and in this case the point driven home by the fool is that people are “saved” to the extent that they maintain their status as free persons while performing whatever role is handed them, be that role one of hardship or joy, and in that way become more themselves.

Dare I say that we have the makings here for the authorial prowess Leonard was later to become famous for, once he had solidified his anthropological vision, devised a way to write in a sunny way about love-making without simultaneously ignoring sex, and begun to focus in a more covertly Christian way on moments when formerly asleep persons wake up? I submit that we do, and for this reason we should all of us be thankful—both for Library of America’s decision to publish Leonard’s early work, and too for Terrence Rafferty’s editorship.

Yet it should also be pointed out that there is a problem attached to Library of America’s overall strategy, for Leonard’s actual transition from traditional Westerns to more urban or at least eastern “Westerns” doesn’t come into view, anywhere, in the four volumes that Library of America has allocated for showcasing Leonard’s work. That’s a serious lapse. I suppose it makes a kind of sense, given that Library of America evidently felt obligated to present the best of Leonard’s work, rather than a mixture of good novels and bad ones, but surely a novel that marks a mid-career effort to ground writing in what one sees and hears outside one’s window rather than in the requirements of genre fiction merits our attention every bit as much as, say, a novel where an author demonstrates mastery of one kind or another.

Given that prior to this current volume the organizing principle for Library of America’s Leonard project had been to group novels according to whichever decade they appeared in, given too that a volume devoted to the 1970s had already been published, might it not have made sense for Rafferty, the Westerns editor, to strike the relatively weak Forty Lashes Less One, which came out in 1972, and insert in its stead the admittedly flawed but crucially important “new” Western entitled The Big Bounce, which appeared in 1969? This latter novel features Mexicans, cucumber fields, high noon scenarios, and Catholic prayer life every bit as strongly as Saber River does, but it is also set in a resort area just north of Detroit on Lake Huron, and—even more importantly—it shows Leonard searching for ways to transplant his anthropology into the soil of that new locale.

The hero of The Big Bounce is a petty car thief named Jack Ryan, who surfaces later as a server of court summons in Unknown Man #89 (1977), the novel Leonard wrote right before Touch (1978), and the “bounce” referred to in the title seems at first glance to be the thrill that can be associated with vandalizing property. Over the course of the novel, though, one begins to see that there are also other “bounces” going on, among them the possibility that a girl who introduces Jack to new varieties of breaking and entering may be using Jack for lethal purposes of her own, and the hook is that the biggest bounce of all may come from Jack’s ability to recognize that he is being played and then walk through a kind of spiritual door toward goodness that he has glimpsed in a stolid, cigar-smoking justice of the peace who buys Jack a beer, and too in the actions of a priest saying Mass for migrant laborers in a field, on the other side of some trees. The Justice doubles as president of the local Chamber of Commerce and his name is Majestyk. To Ryan, “the guy looked like an ex-pro guard hunched over the bar, leaning on his stubby arms … talking to the bartender about fishing,” and when Ryan claims a nearby stool Majestyk sees that Ryan is a fellow who is destined to appear soon in his courtroom. “So how can you be arrested for vagrancy,” he asks. “You ever been picked up for that?” Soon they are drinking Seven Crown and Strohs, and eventually it comes out that a grim reaper claimed Jack’s father when the man was only forty-six. “Well, I don’t know,” Majestyk says. “Sometimes a person just dies.” “Yeah, I guess we all have to die,” Jack says. “I don’t mean that,” Majestyk says. “I mean, we’re supposed to die. You can’t kill yourself but that’s what we’re here for—to die. Are you Catholic? With your name I mean … You were taught, weren’t you?”

I could go on but I think my point is clear. It is this. If we’re serious about getting a firm grasp on Elmore Leonard’s stupendous accomplishments we should by all means acquire the four handsome volumes of Leonard novels now gracing Library of America’s list. That done however, we should make haste to supplement that purchase by acquiring also The Big Bounce so as to see Leonard at his own professional crossroad. Should we see the movie version of the novel as well? I think not. That film stars Ryan O’Neal and when Leonard saw it, he walked out. “I have now seen the second worst movie ever made,” he said, adding: “There has to be one that’s worse.” One month later he recovered by catching Count Basie with jazz singer Carmen McRae at Whisky a Go Go in Hollywood, but we don’t have that option anymore so we, for our part, need to be more careful.

Will Hoyt operates an inn for oil and gas workers near Wheeling, West Virginia.