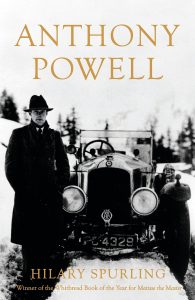

by Hilary Spurling.

Hamish Hamilton, 2017 (Knopf 2018).

Hardcover, 509 pages, $29.70.

Reviewed by James Baresel

Over four decades ago the novelist Anthony Powell asked his friend Hilary Spurling if she was willing to be his biographer. He was, at the time, unsuccessful, though she ultimately came to change her mind and, seventeen years after his death in the year 2000, finally publish the work he had once asked her to compose. The previous books of Mrs. Spurling could only interest readers’ interest in Anthony Powell: Dancing to the Music of Time, books which gave every indication that her biography of her deceased friend would match my preferred subjects of study by being a “personal biography” rather than a “critical biography.” Such expectations were not disappointed. Anthony Powell does not fail to include an account of its subject’s development as a writer, or of those people, incidents and experiences which influenced his aesthetics and his fiction. It does, however, address such topics in the context of his life’s story, as one among many aspects of his life, rather than use the outline of his life as the context within which to submit them to critical examination.

Born in 1905, Anthony Powell was to become part of what was arguably the greatest generation of English novelists. It is a fact which, both in his own lifetime and since his death, has probably done more to obscure his reputation than to enhance it. Being an excellent writer cannot assure that one will attain or retain the high profile proper to one’s merits when the “competition” within one’s own generation includes such towering figures as Graham Greene, George Orwell, and Evelyn Waugh—all three of whom were among Powell’s friends and professional associates. So too were leading poets, journalists and talented minor novelists, among whom can be numbered, in their proper categories, John Betjeman, Malcolm Muggeridge, and Nancy Mitford.

The future novelist’s background was unremarkably upper middle class. His father was a career soldier who had first been commissioned as an officer at the time of the Boer War and who had received fairly rapid promotion during the First World War before his career imploded prior to the Second. The family lived an even more nomadic existence than that typically necessitated by military life, a fact largely explained by the eccentricities and asocial tendencies of Powell’s parents. Powell first had something that approximated to a stable home as a student at Eton, the school at which he first developed a friendship with someone who was to significantly influence England’s literary and artistic world—the aesthete Harold Acton. Eton was followed by Oxford, where Powell’s interest in the historical scholarship for which he was pursuing a degree declined in favor of an increasing strong interest in rhetoric. Fortunately for his professional future and for the literature of the English language, his country’s scholars were at the time expected to attain a facility in the elegant use of language which is not only rarely aimed at in today’s academic world but is often actively discouraged by it.

In 1926 Powell obtained a job in the publishing house of Gerald Duckworth & Co., and soon turned to regular freelance writing as an additional source of income. Beginning with The Afternoon Men in 1931 and ending with The Fisher King in 1986, Powell authored almost thirty books—the twelve volumes of his A Dance to the Music of Time, plus half a dozen other novels, a five volume series of memoirs, plays, literary biographies, and collections of critical essays. It is an impressive body of work, one which may not have been completed in its entirety had not Powell become a man of independent means thanks to the inheritance which he received from his father. Until then he had, at times, had to read dozens of books a week for his freelance reviews in addition to his “day job” as a publisher. Any critical comparison of his later novels with his earlier ones must take into account not only his maturation as a writer but his transition from a man who was more than overworked to something like a man of leisure.

The one real hiatus in Powell’s writing occurred in consequence of World War II, during which he put aside his career to take part in the defense of his country. Even in that time of crisis it was unusual for a man to become a junior officer while approaching middle age. (More common was the fact that his time as a writer turned temporary soldier ultimately provided him with more material to contribute to literature than ability to advance the military effort of which he was a part.) Appropriately for a man with his education and for one who had widely travelled in Europe, possessed no particular qualifications for military leadership, and was at his stage in life, Powell spent the war as a staff officer. Most of his assignments were officially classified as intelligence, though this usually reflected technicalities in the chain of command rather than the nature of his duties. The latter were in themselves simple enough, Powell finding the training courses which he had to attend on the historical and political contexts of the war to range from the absurdly elementary to the inane. After the war ended he was one of those with the perception to realize that the condition of Europe remained catastrophically worse than it had been at any point in the thousand years before Hitler’s attainment of power.

The alarming and rapid decline of a traditional social order that Powell witnessed resulting from the war might best be described as an ever-present undertone in his most famous work, rather than its theme. He was too good an artist to treat his novels as a mere vehicle for social criticism. Recognizing that literature belongs to the life of contemplation, leisure, and aesthetic enjoyment, and possessing the traditionalist’s preference for private life, Powell had no time for the political left’s idea that political “engagement” is part of the job of an artistic writer, or the belief in an incessantly activist populace of which the foregoing attitude is a part. His censorious stance towards the British political parties of his lifetime has, together with his scorn for the “mass politics” and populism of the modern world, resulted in an impression of political indifference. Failure to correct such an impression is one of the few flaws in what is in most ways a highly informative book about Powell and his relationships with the other great literary figures of his generation.

James Baresel holds a Bachelor of Arts in history from the University of Cincinnati and a Master of Arts in philosophy from Franciscan University. He has taught classes in English, Latin, religion, and the history of art.