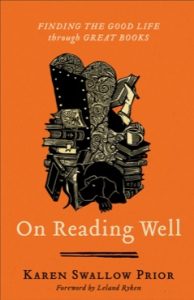

by Karen Swallow Prior.

Brazos Press, 2018.

Hardcover, 272 pages, $20.

Reviewed by Daniel Buck

Society needs literary critics. Time being a scarce resource, they help us to sift between the gold and the dross, the beautiful and the mediocre. They keep us from wasting time on a forgettable film or mediocre book. They provide an invaluable service.

A few works of literary criticism rise above mere sifting and sorting to stand as important works of literature in their own right. Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy is a rumination on the link between high art and politics. T. S. Eliot defended traditional literary theory, humanity’s relation to the past, and the importance of high art throughout his essays. Harold Bloom remains our great canonizer. Karen Swallow Prior has added another book to such a list.

Something of a celebrity English professor, Prior sets out in the introduction to On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books a vision for what constitutes quality reading before she then models some through the summary, analysis, and reflection of twelve essential works of fiction.

According to Prior, reading ought to be enjoyable. It should also be “promiscuous,” meaning ideologically diverse; through reading widely, we experience eras and cultures outside of ourselves, ideas we would never consider on our own, and live vicarious experiences that we would never live otherwise. However, Prior warns that reading should not always be easy. “A book that requires nothing from you,” she writes, “might offer the same diversion as that of a television sitcom, but it is unlikely to provide intellectual, aesthetic, or spiritual rewards long after the cover is closed.” As such, reading ought to take time and even effort.

At the center of reading well rests virtue. Prior distinguishes between innocence, with which neither good nor evil is known, and virtue, with which an individual possesses knowledge of both good and evil and chooses to do good. Through reading, we learn of good and evil, and through reading fiction, we vicariously experience choice and consequences. She calls to mind a short passage from Milton:

Since therefore the knowledge and survey of vice is in this world so necessary to the constituting of human virtue, and the scanning of error to the confirmation of truth, how can we more safely, and with less danger, scout into the regions of sin and falsity than by reading all manner of tractates and hearing all manner of reasons?

In essence, then, reading great literature fosters experiential learning without the risk that comes with real experience. We can watch Romeo and Juliet throw everything away for passion and experience the consequences without having to do so ourselves. We can live under totalitarian regimes from the comfort of our homes. We can even peer into the minds of others.

However, Prior is careful not to associate reading well with didacticism. Reading is not a means to an end but an end in itself with various benefits.

Reminiscent of Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon, Prior reviews and analyzes important works of literature. However, her entries differ from Bloom’s in two important ways. First, Prior’s writing is eminently readable. Bloom’s entries are essentially a collection of academic papers in which he expects his readers to have familiarized themselves thoroughly with every text discussed. Prior, however, provides both summary and analysis in her work, making it accessible even to those who haven’t read every book discussed.

Second, and more importantly, Prior organizes her book based on twelve essential virtues, calling to mind a sort of literature-based Nichomachean Ethics. It is this organizational structure that sets her book above standard literary criticism. Prior has paired polemics and narrative to both instruct and persuade. In each chapter, she uses a work of narrative fiction to extol and analyze the nature of each virtue, resulting in a work both entertaining and edifying.

When reading Bloom’s Western Canon, I felt compelled to read a few works of literature that I hadn’t. When I read critical reviews in a magazine, I am entertained. Reading Prior’s work, I was convicted. Have I been patient with my students? What does courage look like in the twenty-first century? When has my arrogance won out over a biblical call to humility?

Along with its merits in itself, Prior’s book also arrives at an essential moment in politics. In American schools, classic literature is losing its place of preeminence. I’ve taught in districts moving towards curricula based on student choice of mostly young adult fiction. Movements like #DisruptTexts are trying to remove works like Homer and Shakespeare from K–12 reading lists. In my teacher training program, it was assumed that none of us actually wanted to teach canonical works of literature and our discussions focused instead on what to do if our schools required it.

Similarly, I read an essay recently from education scholar Mike Schmoker that declared literacy the “single most important goal of schooling.” There’s certainly a case to be made that it is the primary goal—all other learning and benefits of schooling come from reading—but I worry about an over-focus on literacy as the only goal of literature classrooms.

Reading in school must exist to do more than simply boost literacy scores on standardized tests or provide mere entertainment. While these goals are well and good to a point, placing entertainment or relevancy as the sole criterion for academic instruction sets a school, and its students, up for failure. Video games like Call of Duty will always win out as more relevant and entertaining to an adolescent than a novel.

Prior’s book offers an antidote to such theories of education. Books ought to be entertaining, yes, and any school should use the literature classroom for literacy instruction. However, instruction about literature cannot end there.

Looking through Prior’s reviews, A Tale of Two Cities does not just offer insights about history but a powerful reflection on justice and self-sacrifice. The Death of Ivan Ilych isn’t just a modicum through which students can practice advanced vocabulary but a powerful narrative about the fear of death and the power of unconditional love. Ethan Frome helps students with more than fluency; it’s a warning about the harm we can wreak upon others when we forgo chastity. As the canon wars seemingly reignite in public schools, Prior’s book is an essential reminder of the importance of great works of literature.

As a final commentary on the book, I must say that, as Prior argues reading should be, I found this book simply enjoyable to read. It led me to peruse books I’d read years ago, like A Tale of Two Cities, or to find myself encouraged to pick up one I hadn’t read before, like The Road. Prior’s central thesis is that reading shapes our minds, our characters, and our language. I found, as I read On Reading Well, that this book accomplished all of these goals and more.

Daniel Buck is a teacher and freelance author who writes about education and literature for sites like The American Mind, Quillette, RealClearPolitics, and City Journal.