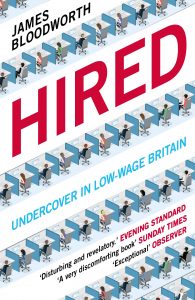

by James Bloodworth.

Atlantic Books, 2019.

paperback, 288 pages, $16.

By Gerard T. Mundy

Communal institutions keep the classical liberal–free market state from implosion. As the strength of what this essay identifies as the six communal institutions—the nuclear family, the extended family, the neighborhood, the church, the voluntary association, and the employment association—begin to wither, a classical liberal–free market state society devolves into the atomistic, cutthroat scenario that political theorist Thomas Hobbes thought wrongly was the natural state.

Economic systems are good when they both defend the dignity of the person and bolster these six communal institutions. The globalism, individualism, and atomization effects of the contemporary American economy, however, do not help to bolster the dignity of the person and the six communal institutions.

The Six Communal Institutions

The six communal institutions are what have kept the negative effects of the market moderated. As those institutions declined for a host of reasons linked to modernity, there was a less robust taming of the market. The market’s inner logic then capitalized on this void, the effects of which ultimately contributed even more to the six institutions’ decline. The cycle is a vicious one, and it is not relegated only to the United States, but rather to the industrialized Western world.

As the six communal institutions have declined, the dignity of the human person has been affected, both in the United States and in Britain. This effect is captured in James Bloodworth’s book Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain. As the title suggests, Bloodworth, a British columnist and journalist, goes to work in several full-time working-class jobs—as, a “picker” at an Amazon fulfillment factory, a construction day laborer, a home health care aide, a call center representative, and an Uber ride-sharing driver.

The title of the book reveals a little of the narratives that exist alongside the tales of Bloodworth’s “undercover” jobs: First, some contemporary employment violates human dignity and, second, contemporary economics have ravished communities in England, thus bringing their people to face considerable existential and psychological distress. Bloodworth’s tales of despondent English communities reeling from economic changes could be the stories of any struggling American town.

That Bloodworth’s tales of economically struggling working-class English people and their towns could be substituted for the prototypical economically struggling working-class American town only solidifies the fact that the issues afflicting these American communities are not uniquely American at all. Rather, the afflictions are present throughout a Western world struggling to understand the effects of an economics that has, for all of the positive words so many heard and perhaps spoke themselves in previous years, come to have adverse effects on people and their communities. Neglecting and ignoring these effects will no longer be tolerated by the people most affected by them. The United Kingdom’s “Brexit” vote to leave the European Union was the British version of the 2016 American presidential election and illustrated this point.

As Bloodworth writes: “I had set out to write about the material poverty that often accompanies precarious work, but I quickly realised that it was just as important to write about the British towns I was living in.” Although Bloodworth’s focus was to chronicle life, undercover, in working-class jobs, he could not ignore the state of the towns in which he performed these jobs. In Bloodworth’s estimation, the loss of good jobs in these towns have made them shells of what they once were, and so the reader who cares about how communities can help or hinder people’s flourishing might be found focusing on this aspect of the book more than others.

Man Cannot Live by Economics Alone

Bloodworth is not seeking to write a treatise on how to ameliorate the problems he encounters in the undercover jobs he takes. He is, however, certainly a proponent of, and enamored with, employment unions. Throughout the book, even at times when one might not expect such an insertion, Bloodworth’s writing seems more like advocacy in his praise of the “solidarity” that unions have previously provided. Unions are an immensely helpful voice in ensuring that workers are respected and they also can be incredibly helpful in ensuring a just and moral society. For all their positive effects, they are not a cure-all for the problems that plague the modern soul.

Bloodworth’s nostalgia for powerful unions is innocent enough and seems to be coming from an individual who sees the suffering of individuals and communities but can only envisage one basic cure. But unions are not a magical antidote, for the economics problem is only one of many effects of modernity. Indeed, the problems facing the modern soul are neither solely caused by economics nor can they be solved only by economic changes or reforms. Indeed, the problems plaguing people and communities throughout the West cannot be miraculously cured by any singular type of secular association or political fix.

Terrible jobs are not characteristic only of this age, which often escapes Bloodworth’s book as he romanticizes past employment and the unions associated with those jobs. Working today an unfulfilling job in an Amazon factory can be as unfulfilling as digging yesterday by hand the tunnels of the New York City subway system. Respecting the dignity of the worker is paramount in this discussion, but simply ensuring or providing due respect does not necessarily create strong communities. What gives people meaning outside of terrible jobs is that which can truly lead them and their communities to flourish. The breakdown of family, community, associations, religion, and moral authority give people little ways to find fulfillment outside of a job and the money that the job provides.

Human beings cannot be fulfilled simply by their jobs, whether minimum-wage factory jobs or six-figure executive roles. Their dignity must be recognized and respected while they work, but to believe that one can be fulfilled fully in a job role will only lead to disappointment. No one who does not have in view a proper end in life can reach any semblance of fulfillment.

Undercover, Bloodworth laments the sight of some of his fellow workers who attempt to find fulfillment in consuming drugs, alcohol, and junk food. Bloodworth is right to argue that they engage in these risky behaviors because these are false fixes in which they are trying to find fulfillment and happiness—but again, a good job is not a panacea for all that ails them.

When there are fulfilling associations outside of a particular job, people have something for which to live. Family, community, and associations provide outlets in which they may find their purpose. Religion provides them with a meaningful end. Proper moral authority (which in the West had been dominated by religious authority) provides guidance on how one may check the passions. When all of these are lost, the strength of employment wages, benefits, and conditions mean little.

Hired provides only a few references in passing to the loss of these associations. This is not enough. (There may also be personal biases present: Bloodworth mentions the loss of religion as a problem once, halfway through the book, in one measly sentence that paints religious faith negatively.)

Larger Issues in Modern Work

Bloodworth wrongly depicts a picture of an economy that mistreats only working-class workers. The modern Western economy does not discriminate in this regard. It mistreats workers at all levels when there is a loss of moral values and sense of community among workers and employers. One would think Bloodworth would recognize this larger problem, but that might negate the book’s whole sensationalist premise of going undercover to see the grimy underworld of working-class jobs.

For example, in one of his featured jobs as a home health care aide for the elderly, Bloodworth discusses how little time he was afforded to care properly for these individuals. The author recalls: “We were racing against the clock and it was the customer who lost out. That, after all, was what they were—a customer, engaged in a frigid transaction with you, a representative of the business” (original emphases). This scenario, however, is not relegated only to low-wage work or only this type of work. It is ubiquitous in the contemporary economy. Somewhat related to this point, Bloodworth seems to equate “low-wage” with “working-class” and to use the terms interchangeably. There are, however, “low-wage” jobs that are not filled by “working-class” folks and “working-class” jobs that are not “low-wage” positions.

Bloodworth’s book chronicles the stories of despondent communities filled with individuals who are lost, sad, and alone. The fact that their jobs are gone, and that the remaining jobs are with corporate behemoths that demonstrate little care for the needs of their workers or their communities outside of the minimum needed to ensure profit, is but one part of the story. The larger picture includes these economic changes along with the decline of family, community, associations, religion, and moral authority. In conjunction, one sees the landscape of the modern Western world.

Bloodworth’s misplaced nostalgia is evident throughout the book. He argues that “The sorts of jobs that once gave local communities their identities are gone.” It was not, however, that the jobs themselves were necessarily good; rather, it was that good community bonds were properly formed around them. When most men in the small community worked in the town mill, the bonds that they made as a community is what got them through the work and gave them purpose. It was not the work or the job itself that gave them reasons to live.

The Takeaway

What Bloodworth’s book does well is to provide the words and stories of some of the wandering people of this modern era. The book might be lacking in its perspicacity and in some philosophical ways, but it provides a solid on-the-ground journalistic account of some of the day-to-day issues in contemporary working-class employment.

If one can bracket off the issues highlighted above, the book provides readers an interesting first-hand account of some of the miseries of the Western people of today (with a stress on “the Western people of today” and not, as Bloodworth implies, only low-wage working class people). Bloodworth’s care for the dignity of the human being, and his concern for the working class and declined communities provides a framework through which he sees certain issues and with which some on both the left and right can agree.

Aside from his fervent support of unions, there is a refreshing balance in the book, with Bloodworth criticizing both the political left and right by showing the deficiencies of both enlarged, ineffectual government and of companies that seek only profit without taking into account moral considerations.

Gerard T. Mundy teaches philosophy (political philosophy/political theory specialization) at a private college in New York City.