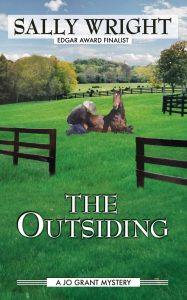

by Sally Wright.

Amazon Digital Services, 2018.

Kindle, 1038 kb, $3.

Reviewed by Ashlee Cowles

Why do we read fiction? A cynic may claim it’s to avoid reality, but the devoted reader knows better. We read stories, including the made-up ones, not out of a desire to escape this world, but in order to encounter what is most true, most real, within it. Sally Wright, the Edgar award-nominated author of the Ben Reese and Jo Grant mystery series, wrote about reality. She crafted stories that showcased the human condition at its most universal, but Wright also did what the best storytellers always do—she transported the reader to a particular time and place, and in so doing, enabled the seemingly mundane details of life to reveal what makes us human.

After a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer that projected just six months to live, Sally Wright battled the disease for seven years. She passed away on June 15, 2018, but her clear voice is still with us, distinct in its elevated prose and reasonable civility. It’s a voice we desperately need to hear in an age where angry Twitter mobs are increasingly granted the power to decide which books get published—and which ones don’t. As I read The Outsiding, Wright’s final and posthumously published book, I was struck once again by her lucid descriptions.

The story is set in the 1960s in bluegrass Kentucky, a region not far from where I was born, though I have no memories of its landscape. Wright brings the people and culture of the thoroughbred industry alive in unexpected ways. Reading about the care and breeding of horses evoked the James Herriot stories I adored as a child—a master of research, Wright knew her equine medicine—and her study of intricate relationships in a rural community recalled the poetic storytelling of Wendell Berry and Elizabeth Goudge. Although Jo Grant—architect turned broodmare farmer—is the detective protagonist of the series, The Outsiding is largely centered around the mother-son relationship between Meg and Michael McIntyre:

March had started off cool in Kentucky, and Meg had lit a fire, and they sat on either side of the big stone fireplace, while logs collapsed and smoldered, and flames and sparks shot skyward, in a quiet, darkening night, the fragrance of wood and smoke taking them both back to childhood, soothing their brains and their bones.

Meg had brought coffee and oatcakes she’d baked that afternoon, and she was watching Michael the way she had since he’d been born, knowing somewhere underneath her ribcage that something was coming that wasn’t good news, while he talked about his dog, Wolf, and the gelding he was training.

Meg, an aging widow and owner of the veterinary clinic where her son works, is thrust into conflict when Michael reveals that the managing vet, Dutton Harris, is doing more than cutting corners that threaten the reputation of their family business. He’s involved in something far more sinister, a greedy scheme that results in dead horses … and dead people.

The cozy mystery that unfolds will keep readers turning the pages, but primarily because we care about the believable and well-crafted characters. One of the most emotionally effective devices Wright employs is the way she writes the mother of her villain as a foil for the much healthier relationship between Meg and Michael.

“Was it me? Am I responsible for what he’s become?” asks the tearful mother in a moving scene reminiscent of a courtroom drama where a baffled parent must watch as the jury convicts her child of crimes she’d never think him capable of.

“No,” Meg tells the humiliated woman. “[He] made himself who he is now. With one choice after another.”

Thus we arrive at a theme central to all of Sally Wright’s novels, a theme at the heart of the mystery genre itself. Even if our generation, culture, and upbringing are influential forces that shape who we become, human beings possesses free will. There is good and there is evil, and we always have a choice. But again, Wright’s novels never deteriorate into moralistic preaching. Her matter-of-fact prose speaks to her faith in the intelligence and humanity of her reader, which enables Wright to show us what is good and just through the dialogue and actions of her characters. This clear-headed style is refreshing at a time when “virtue signaling” is often given preference over portraying what real, complicated human beings actually do and say.

The novel’s final scene is a stunning portrayal of the “permanent things”—of small, daily acts that cultivate the simple beauties that keep the darkness at bay. Writing in her journal, Jo Grant describes her admiration of Meg and the way her elderly friend spent her remaining days: “still learning, still teaching piano, still reading and working in her garden.”

“She set me a very good example of what I hope to be able to do for as long as I’m given time,” Jo concludes.

As a novelist at the start of my own writing journey, I can’t help but marvel at this poignant statement—the last line of an author’s ninth and final book—for it tells us how we ought to view the life and creative career of Sally Wright. May we all learn from her example and spend our fleeting time on this earth pursuing such meaningful and lasting work.

Ashlee Cowles is a former Russell Kirk Center Wilbur Fellow, a literature teacher, and the author of the novel Beneath Wandering Stars (Simon & Schuster 2016).