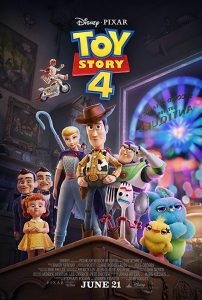

Directed by Josh Cooley.

Pixar Animation Studios, 2019.

Reviewed by Titus Techera

After a fairly disappointing season, the movies got back to the magic that audiences still crave, with what looks to be the family movie of the year. Toy Story 4 is the end of a fantasy with which an entire generation grew up—the first movie came out back in 1995 and announced Pixar as America’s favored dream-makers. They took on the job of dealing with the nation’s emotional education, knowing that, unlike with real people, with animations we crave sentimentality.

To understand Pixar’s achievement, consider that Disney’s most famous productions are rarely American stories. Disney made his name with European fairy tales or British children’s stories: Jungle Book and Mary Poppins. The recently remade Dumbo was a rare American story back in 1941. Disney of course now owns Pixar and times have changed, but American stories are still different, even when they’re aimed at families, because we don’t have the medieval past necessary for fairy tales.

Hence the surprising achievement of the Toy Story franchise. You can tell because the fourth installment is a movie everyone loves even before having seen it, and which everyone will love after they see it, perhaps multiple times. This is incredibly rare—even movies that make vast amounts of money tend to be forgotten instantly. More or less the same was true of Toy Story 3, which came out back in 2010. Notice that these movies do not have the subtitles ubiquitous everywhere else in franchise movie-making. They’re unnecessary. The core of the story, the love of children, suffices to attract families.

By the third installment, it became obvious that adults gave up and that children’s loves and likes ruled the newest form of movie-making: animation. Unlike in Japan, where a master of cinema like Miyazaki can make heartbreaking, adult stories that simply wouldn’t be fit for children, our animations obey something like a sacred boundary—we wish to shield our children from suffering, even in their imaginations, where we nevertheless try to smuggle in experiences from which we protect them in real life. Animation has been the last refuge of the family at the movies.

Since the story is over with this fourth installment, giving audiences the needed relief of an emotional conclusion, we can now say a few things about its peculiar idea. The toys in Toy Story are American parents. They live, in a way, in fear of their children, who inevitably grow up, move away, and abandon their parents like old toys. All the earnestness in the movie is based on this simple reality we all know, but do not acknowledge. That is what makes the story compelling. Silently, we can admit our suffering. In some ways, children tyrannize us—what’s peculiar and requires this indirect, comic treatment is that they do so with our often-enthusiastic consent.

Moreover, this is considered a requirement for success for Americans, if not success in itself. We believe, as Americans, that everyone everywhere is the same since all people are equal, but we are unique on this planet in setting our purposes on this form of abandonment—leaving all behind and going off to college, the theme of the third movie in the series. To build a society on the principle that the world should be a playground for children and then to have to deal with abandonment is hard indeed on its inhabitants.

In a way that children themselves cannot understand, Toy Story is what we watch to allow our suffering to come out. The film franchise is as close to a public purging of our passions as anything. We all want to do what’s best for children, but we cannot help wanting to hold on to our own children. We give our children to America, that they may have a future. But in each story, freedom turns out to be a very dangerous thing, an entire drama—dangerous to the family and to home.

Letting go is hard, but since we cannot help it, we must resign ourselves. This is what Toy Story 4 is about—parents who have to learn to live their own lives without children once they leave for college. Toy Story 3 had dealt with Andy leaving for college—it was goodbye for the boy whose happiness the toys selflessly served, and therefore on whom their self-understanding depends. This time around, America’s most lovable actor, Tom Hanks, also has to say goodbye.

Woody has to learn to trade one love for another. He begins the story by remembering Bo Peep, the love he had long ago lost because he chose Andy. Well, they happily find each other again. She’s the obligatory smart, tough, witty, lovable girl in the movie—animations, like anything else, are required to have one of these characters nowadays. But the writers take this political piety and work it into the story startlingly well, since the whole film is about freedom, leaving things behind, not being too attached. Strong, independent woman is exactly the ticket.

Woody would prefer never to part with his kid—Bonnie, to whom Andy had given him—and he proudly and angrily calls that loyalty. But Bo Peep thinks, like it or not, your kids leave you behind and you have to square with that fact, so that you can make your own plans for your own life. You may think it strange to have the male character so clingy and the female character not attached to any child, but it certainly fits our politics right now.

Woody is no longer a parent now; he’s turning into a grandparent, and it’s tiring him out. He says that he forgot how hard it is to deal with a young child. Bonnie, the child, is preparing for kindergarten, where she makes a new toy out of a spork, and it’s up to Woody to teach the new toy how to be, well, a toy. This is all for the kid’s good. Bonnie’s afraid of kindergarten, so she uses a toy to express her feelings and play-act parenthood, becoming bravely protective of something more needy than herself.

This is a big deal in the movie. In another crucial scene we see the same thing happen with a girl lost at a fair. She finds a doll—who of course is a lost toy in search of a child to whom to belong—and quickly becomes brave enough to find a security guard to take her to her parents. In treating toys like their children, these kids learn to imitate their own parents. It’s part of growing up, or should be. That toys should be alternately parents and children is a very useful metaphor for the reign of equality in America, including in our homes.

This is where the story shows the darkness underneath the humor. No need to worry—children never see these things, but adults do, or should. The spork tells Woody that it’s not a toy, but trash. It longs to end up in the garbage. This suggests how throwaway our possessions are, how fickle our own desires, how the many choices in which we invest great feeling are nevertheless a matter of chance. Change comes upon us unexpectedly and we feel that nothing lasts. This is what I meant when I said Toy Story is all-American, utterly without the romantic or nostalgic quality of European fairy tales.

Woody teaches the spork that Bonnie believes it’s a toy, so it must understand itself as a toy. The whole adventure of the movie is about getting this point across. The spork learns to feel loved and needed and begins to take its responsibility as an adored whim seriously. The spork learns to stop being afraid of children and toys, which may be a comment on Millennials …

Woody and Bo Peep now seem more like grandparents. They have aged in an invisible way and must ask themselves what they could do with their lives when they’re no longer needed by their children. Family and freedom are constantly battling it out in the American soul, and freedom seems to be winning in storytelling, which is a strange form of defeat, as any resolution of tension must appear. Since children are free, so their parents must become, but the price of freedom turns out to be loneliness.

This is the melancholy conclusion of the most beloved children’s story in a generation. We had all signed up for magic and family only to see family transformed until it is no longer recognizable. It is at any rate redefined by freedom, and it’s not clear what might fit as a metaphor for parenthood in future storytelling. Trying to fend off the sense that we’re all as disposable as trash has gotten much harder, and I wonder what family movies have left to offer.

Titus Techera is executive director of the American Cinema Foundation and a contributor to National Review Online, The Federalist, Modern Age, and Liberty & Law.