By Paul Kengor.

TAN Books, 2024.

Hardcover, 416 pages, $29.95.

Reviewed by Paul Krause.

The crucifixion of Christ is the central event in Christianity, for, as Saint Paul says in his letter to the Corinthians, “we preach Christ crucified.” After the resurrection, Christ appeared before Saint Thomas, showing the distressed and doubting apostle his wounds which, upon touching, Thomas proclaimed Christ “my Lord and my God!” Since then, a few Christians have been bestowed the gift of the stigmata, the wounds of Christ, appearing on their own bodies.

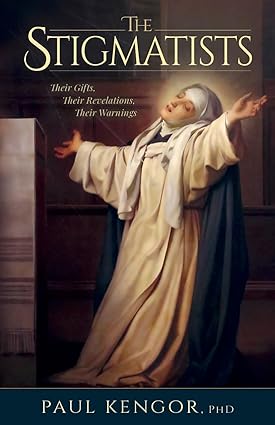

Despite two millennia having passed this the seminal event of Christianity, Paul Kengor notes, “There have been very few books that offer a serious, reliable, careful look at the stigmatists and, specifically, what one might call visionary stigmatists.” That is, until now. The Stigmatists: Their Gifts, Their Revelations, Their Warnings is Kengor’s latest book which fills the gap in scholarship looking at the visionary stigmatists who dot the historical landscape of Christianity.

To be a stigmatist, one must bodily possess visible wounds akin to the wounds of Christ—the pierced hands, pierced feet, or pierced side, but usually pierced hands. Stigmatists are, as Kengor concisely calls them, “living crucifixes,” for the “[s]tigmata are physical marks reflective of and representing a participation in the sacrificial Passion of Jesus Christ as His Crucifixion.” While one can have wounds that mirror the wounds of Christ, Kengor reminds readers why the stigmatists are so rare despite the modern prevalence of forgery and the ability to undertake fake wounds for the purpose of spiritual deception: “A key test of authentic stigmatization—not faked nor of diabolical origin—is the character of the individual.”

Thus, Kengor proceeds in his history of key stigmatists through Christian history, looking at the medieval stigmatists of renown including Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Catherine of Sienna, to more modern stigmatists of the past century including Saint Padre Pio and Saint Faustina. A common unifier among the stigmatists in Kengor’s study is the fact that all the persons he examines, male and female, are either saints or beatified souls—“Blessed”—and therefore on the path to sainthood. These individuals do stand out as having the best of “character,” inspiring moral souls who stood out and shined as lights in the darkness during the times in which they lived.

I wish to look at just a few of the stigmatists in this study, starting with Saint Francis of Assisi. Francis is, as Kengor introduces him, “one of the most revered names in the Catholic Church, if not in Christendom as a whole.” As we know, Francis was the medieval monastic reformer who highlighted the need of ecclesiastic reform and revival during the Middle Ages, he ventured to Egypt to discuss theology and philosophy with Sultan Al-Kamil during the Fifth Crusade, and he emphasized the sacramentality of creation by preaching the love and goodness of God to all creatures of the world, not just humans, reminding all of the beauty and grace of God through creation.

The purpose of beginning with Francis among the stigmatists is the fact that Francis was a visionary who soldiered on in his life despite receiving the wounds of Christ for the sake of the vision he had received from his Lord. For Kengor, this introduces another unifying thread among the stigmatists profiled in this enlightening read: the holy and inspiring visions they had and not just the physical wounds that mirrored Christ. In 1205, when Francis “sought solace at the church of San Damiano,” the icon of Christ in the abandoned church is said to have directly spoken to the young man with the command to “repair My church.” Francis took Christ’s command literally at first, beginning by rebuilding the church of San Damiano by himself, with his own hands and feet, which inspired others to join. Once the church was rebuilt, it slowly became apparent that the command to “repair My church” meant much more than an individual church—it meant the whole church.

In 1224, Francis received the stigmata on his body, witnessed and attested to by his close friend Brother Leo, and recorded by Thomas of Celeno in his biography The Life of Francis. For many, having the physical wounds of Christ would be a detriment to one’s work. Yet for Francis, it was the opposite. He was invigorated and spirited to continue Christ’s work of repairing the church, calling all to holiness, and inspiring his brother friars to repentance and charity, despite growing frailer and frailer every subsequent year. As Kengor writes, “Despite the nails pressing into his flesh, Francis pressed on, preaching the Word and offering up his sufferings as expiation for the sins of the world.”

Let us now turn to a more modern stigmatist, Saint Faustina. Faustina lived from 1905-1938 during the turbulent decades of the early twentieth century. She lived through the horror of the First World War and died just prior to the even more grotesque horror of the Second World War. In 1924, a dancing and joyous Faustina in a park in the city of Lodz—which was soon to be “ripped to shreds by…totalitarian invaders”—received her vision of Christ. Christ was suffering, beaten, and broken; he called out to her, “How long shall I put up with you and how long will you keep putting me off.”

As Kengor notes, this must have been a staggering and shattering revelation to the 19-year-old Faustina. Poland was a newly independent country and had just fended off an invasion by the Soviet Union. The death, destruction, and suffering of the First World War and the Polish-Soviet War would have been an afterthought for the young girl. Why was Christ appearing to her in suffering when the Polish people, among so many others, would have been looking to a new future with hope? Kengor aptly captures the mood: “One can scarcely imagine the young girl’s shock. Her world must have frozen. Imagine the scene. It was the Roaring ‘20s, not just for America but for much of the world. The brutal First War, then the deadliest in human history, was in the past, and it was time to have fun and live it up.”

This was not the first or last of Faustina’s visions of Christ. Her most famous was in 1931, when, as a convent sister, Christ proclaimed the hollowness of modernity and the false joy which humanity was seeking. Without Christ’s merciful love and compassion, Faustina recalled, the peace and happiness which humans were seeking with their dreams of material and political prosperity would be all for naught. In a world forgetting Christ, her visions recalled the necessity of Christ’s love and mercy in the world.

Faustina received the stigmata across her body: her hands, her feet, even her head. They would appear and disappear throughout her life. Though she suffered and her final vision of Christ was one concerning the catastrophes of the Second World War and the brutality of political totalitarianism which would sweep across Poland and half the world during the later part of the twentieth century, Faustina’s visions also reveal the hope of the world: the love and mercy offered in Christ. Fear not hell, look to the love that lifts you up to heaven!

Paul Kengor’s book is a lively read through the lives of various Stigmatists, their lives, their visions, and their message for us living in the twenty-first century. These are not men and women of the distant past, or even recent past, whose mystic visions and physical wounds mirroring those of Christ are unimportant to us. Their visions are meant for us, and reading Kengor’s book reveals why that is so.

Paul Krause is the editor-in-chief of VoegelinView and the author of, most recently, Muses of a Fire: Essays on Faith, Film, and Literature (Stone Tower Press, 2024).

Support the University Bookman

The Bookman is provided free of charge and without ads to all readers. Would you please consider supporting the work of the Bookman with a gift of $5? Contributions of any amount are needed and appreciated!