by Maurice Isserman.

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

Hardcover, 318 pages, $28.

Reviewed by William F. Meehan III

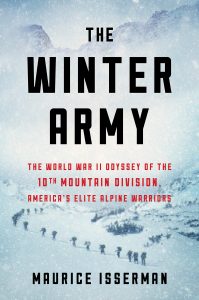

I judged Maurice Isserman’s book by its cover and was not misled. The wording and the landscape image of soldiers carrying backpacks on skis traversing snowy mountainous terrain, in fact, brought to mind my unexpected introduction to the Alpine adventure genre.

It was the annual “Holiday Cheer” gathering hosted by my girlfriend’s parents, where talk at the Grand Avenue home that evening centered mostly on the imagined havoc coming with the new millennium, just over a week away. In the kitchen, however, girlfriend Julie, former singles player for the Ivy League’s Big Green (née Indians), was directing a spirited conversation about the Twin Cities’ indoor tennis league. Her father, Rob, a voracious reader and Yale classmate of William F. Buckley Jr., must have noticed I was mere onlooker to the discussion.

“Here, this is for you,” he said cheerfully, handing me a mass-market paperback. “I finished it this morning. You won’t be able to put it down.”

My reading interest at the time was F. Scott Fitzgerald, for the simple reason that I was living next to the Commodore Apartments, once the fashionable residence for the St. Paul literary lion, and felt some inexplicable obligation to explore his works. Next on the list was a thick collection of FSF’s letters, which I planned to browse on the following day’s flight to Philadelphia. Once in my comfortable exit-row seat, though, I instead opened the book given to me the previous evening.

Rob was not exaggerating. Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster, the gripping story of the deadliest season on the world’s highest mountain, held my attention from takeoff to touchdown and marked the commencement of my pursuit for stories in a literary category previously unknown to me.

Which brings me to Isserman’s book, in media res. Two regiments of a uniquely trained division disembarked at Naples in December 1944 and a month later were about to face their first test against German forces in the Italian Apennines. They received specialized training, first at a temporary camp on Mount Rainier and later at the permanent Camp Hale in the Colorado Rockies. They perfected winter warfare tactics, which included, besides learning to kill, acquiring survival techniques and grasping the nuances of handling mules, all the while strengthening their prowess in skiing and climbing.

The mission was to seize a vital German stronghold on Mount Belvedere, but they first had to deal with Mount Riva, a 4,672-foot peak. Commanding officer General (two stars) George B. Hays ordered a patrol to scout possible routes up the frozen cliff. Riva Ridge was too formidable, a lieutenant reported back. Hays believed otherwise. “This is a mountain division,” he said. “Surely they can find how to climb up that ridge.” The young officer reconsidered.

Most of the division’s essential winter gear never arrived at Naples, but that did not deter the intrepid ski troops. With a limited supply of crampons and rope, using bayonets in place of ice axes, they cleared five passages up the cliff, from where—after six hours of climbing—the very best of the skiers would the next day glide down the slopes, in their finest Arlberg technique, and surprise the Germans. The division was victorious in the Battle of Riva Ridge, allowing the capture of Mount Belvedere and two months later, when the Germans were about to surrender and usher in an end to World War II, the triumphant march across the Po Valley.

These are the soldiers of 10th Mountain Division, subject of The Winter Army, a delightfully engrossing narrative by Hamilton College history professor Maurice Isserman. The book’s structure falls thematically into training (chapters one to four) and wartime service (chapters five to eight) and thus is evenly proportioned, a commendable accomplishment given the imbalance in the division’s length of time in each phase of its military service. “Two winters at Camp Hale trained us for 10 minutes of creeping and crawling under enemy fire with skis on,” Sergeant Dick Nebecker writes in a letter home.

While infantry regiments were thought the least-educated soldiers, the mountain division attracted graduates of the country’s elite universities, where they typically lettered in three sports. Several of the recruits were members of the Yale singing group the Whiffenpoofs and provided entertainment for the troops on special occasions like holidays or birthdays. Some of the best winter athletes in the division were foreign-born, from Austria, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. In all, according to Isserman, the soldiers in the mountain regiments were better-educated, more affluent, and more cosmopolitan than the average recruit. As a result, the “glamorous” ski troops developed “a finely honed combination of fitness, endurance, self-confidence, and unit cohesion” that contributed to esprit de corps in training and in their short but spectacular time as front-line infantry.

Their training regimen distinguished the mountain division soldiers. In a letter to his parents, one enlisted man describes “the worst physical ordeal” of his life during three weeks of maneuvers at 13,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies:

Saturday night we started on a march on snowshoes and skis through snow that was up to our waists. We hiked until 1:30 A.M., then crawled into our bags and fell asleep exhausted in the snow. We were awoken at 4:00 A.M., and had to pack in a snowstorm (it snowed every day we were out) … For four hours we climbed in that blizzard. Finally, soaked clear through, completely exhausted, and almost frozen, I and another fellow fell out. We hiked back to the temporary base camp after rescuing a fellow who had fainted in the snow and taking him to an aid station. I never thought we could make it; you could hardly see 15 yards ahead.

The idea for a winter army originated, fittingly, in an aprés-ski conversation among four men huddled by a roaring fire at the Orvis Inn in Manchester, Vermont, on a windy, snowy February evening in 1939. The group, fascinated by how Finnish ski troops routinely frustrated German forces invading their country, wondered how the United States would defend itself with a military trained for tropical—not winter—warfare. In other words, What if the Wehrmacht attacked the Northeast in mid-January?

One member of the foursome had what they believed was the solution: train skiers for winter combat. Charles “Minnie” Dole, director of the National Ski Patrol System (NSPS), drafted a proposal and two years later the U.S. Army’s mountain division got the green light. It was agreed that Dole would serve as head recruiter, drawing soldiers primarily from the NSPS, whose membership he knew and could vouch for. For unknown applicants, Dole would evaluate their proficiency on skis and their overall aptitude as determined by three references, usually former coaches who could comment on athletic ability as well as character and intelligence. Army brass later learned the hard way that it is more effective to turn skiers into soldiers than soldiers into skiers.

Isserman’s pertinent qualifications for telling this story of America’s elite Alpine warriors include two National Outdoor Book Awards, one Banff Book Festival Award, and one Pulitzer Prize nomination for volumes about mountaineering—a literary refocus for the scholar whose well-known Which Side Were You On? is, according to The American Historical Review, “obviously sympathetic to the Communists [but] also suitably critical.” It is worth noting, however, that Isserman’s intellectual journey took him to the University of Rochester, where he was mentored by a pair of heavyweights in the fight for reasoned scholarship in a free society, Eugene Genovese and Christopher Lasch.

This narrative about an extraordinary wing of the United States army is testament to the value in primary sources, the original research material housed in an institutions’s special collections department. Initially relying on clichéd phrases borrowed from war movies, Isserman realized he would need first-hand accounts, the words written by the soldiers themselves. He ended up at the Denver Public Library, where he explored a massive collection of letters in its 10th Mountain Division archive and connected directly to the men in his story.

Numbering more than 20,000 soldiers, the mountain division was the last to arrive overseas and the first to be sent back to the U.S., docking at Hampton Roads the day the bomb fell on Hiroshima. Their post-war endeavors varied. Bob Bowerman became the legendary track coach and Nike co-founder. Robert J. Dole, wounded in the final days of battle on Italian soil, returned home to Kansas decorated with a Bronze Star, and later, for his career in statesmanship, honored with the Presidential Medal of Freedom and Congressional Gold Medal.

They were winter sportsmen at heart, though, and “couldn’t get skiing out of our blood,” according to Dick Wilson, who became editor at a magazine that evolved into Skiing. “We wanted to teach the country to ski. And we did.” Thousands of them joined ski patrols or signed on as ski instructors. The more entrepreneurial of the soldiers went on to build resorts, such as Colorado’s Aspen and Vail, Oregon’s Mount Bachelor, and Vermont’s Sugarbush, while indirectly influencing the development of areas like Utah’s Alta. The ski troops served with distinction even after the war. “The 10th Mountain Division,” writes Isserman, “was the only unit in the history of the U.S. military to use wartime skills to promote a civilian pastime.” The Winter Army belongs on the shelf alongside other Alpine adventure stories.

William F. Meehan III is editor of William F. Buckley Jr.: A Bibliography (ISI Books, 2002) and Conversations with William F. Buckley Jr. (University Press of Mississippi, 2009).