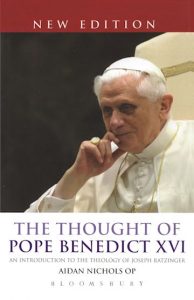

The Thought of Pope Benedict XVI: An Introduction to the Theology of Joseph Ratzinger, Second Edition

by Aidan Nichols.

Burns & Oates/Continuum (London)

284 pp., $24.95 Paper, 2007

Ratzinger’s Faith: The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI

by Tracey Rowland.

Oxford University Press (Oxford/New York)

232 pp., $24.95 Hardback, 2008

When the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church elected Joseph Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI, they chose a theologian who for fifty years had taught, lectured, and written continuously about the most pertinent theological questions of the twentieth century. He was a young professor of theology when invited to serve as peritus at the Second Vatican Council, the central event of twentieth-century Catholicism. Vatican II shaped his theological work for the rest of his career, even after he became archbishop of Munich-Freising in 1977 and later Prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith in 1981. The latter position, one of the most prominent in the Church, placed him at the center of Catholic theological life and charged him with overseeing Catholic theology throughout the world. While occupying this post, it was a matter of some controversy that Ratzinger continued to lecture and write as a private theologian; that his private work included some candid criticisms of certain aspects of the post-conciliar Church was even more startling. Yet the cardinal-electors knew that they were selecting more than a cantankerous professional theologian: they chose instead a man whose theological work was both the source and expression of his profound love of Jesus Christ and of the Catholic Church.

In the weeks and months following the ascent of Pope Benedict XVI to the throne of Peter, countless articles appeared labeling him as conservative or hardliner through the use of epithets such as “God’s Rottweiler” or the “Panzer Cardinal.” Such labels, however, pertained more to his office as prefect, which was actually quite mild compared to his predecessors, than to Ratzinger himself and his theology. In fact, the depth of Ratzinger’s thought not only exceeds these scurrilous labels, but it also requires careful and measured analysis, more so now due to his elevation to the papacy. Meeting this need, the complementary books by Father Aidan Nichols, O.P., and Tracey Rowland offer both comprehensive explanations of Ratzinger’s work and an account of his theological vision, which fixates on God’s revelation through the person of Jesus Christ.

Nichols’s The Thought of Pope Benedict XVI, Second Edition, updates his 1988 study The Thought of Joseph Ratzinger, which was the first systematic survey of the future pope’s work. Nichols, one of the foremost theologians in the English-speaking world, writes with “a modest purpose: to introduce, with a good deal of both paraphrase and direct citation, the principal writings of a German Catholic theologian” who now occupies the primal see of the Catholic Church. After a modest introduction outlining the cultural and theological currents of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Germany, Nichols chronologically examines Ratzinger’s theological investigations, beginning with his earliest work on Augustine and Bonaventure, then to his contemporaneous assessment of Vatican II, then to his later work on ecclesiology, liberation theology, liturgy, ecumenism, and modernity. Nichols concentrates exclusively on Ratzinger’s work as a private theologian rather than as prefect or pope; nevertheless, Ratzinger’s positions in Rome influenced his private pursuits, leading him to consider “not so much scholarly subjects chosen at leisure as the principal disputed issues confronting the contemporary Catholic Church.”

By proceeding chronologically Nichols conveys both the consistency of Ratzinger’s thought, which still remains visible in his writings and speeches as pope, and also small developments in his thinking without dilating upon them. For example, Ratzinger’s conclusions on Augustine’s ecclesiology of the Church as the “people and house of God” and on Bonaventure’s theology of history resonate in his later work; by contrast, while he wrote favorably of the pope as “Western patriarch” in the midst of Vatican II,as pope he removed patriarch from the list of papal titles. Most interesting, though, is Nichols’s summaries of Ratzinger’s impressions of Vatican II and its documents as he wrote them in the 1960s. Nichols acknowledges “Ratzinger’s ‘progressivism’” during the Council as a “short-lived reaction against the Church of the pre-conciliar period”; but he cautions that this thinking “was controlled not so much by the imperative of modernisation or adaptation, aggiornamento, but by that of a return to the biblical, patristic and high mediaeval sources, ressourcement.” The resssourcement movement of the “Nouvelle Theologie,” of which Ratzinger was a part, challenged the old guard in its desire to focus wholly on Christ, not to accommodate Christianity to the modern world.

While Nichols’s summaries, particularly of Ratzinger’s early work, are invaluable, he generally avoids discussing Ratzinger’s thought vis-à-vis his contemporaries and his place in twentieth-century theological debates. In Ratzinger’s Faith: The Theology of Pope Benedict XVI Tracey Rowland, dean of the John Paul II Institute in Melbourne, focuses especially on these issues in her thematic and well-researched survey. With Nichols, Rowland places Ratzinger in the ressourcement movement that after Vatican II centered around the international journal Communio, of which Ratzinger was co-founder. However, Rowland also describes at length Ratzinger’s attraction to St. Augustine and his relationship to Thomistic theology. Although he openly prefers Augustine over Aquinas because the former’s epistemology provides “a very contemporary intellectual profile and a bridge to the post-moderns,” Ratzinger “is not shy about using Aquinas as a source.” However, in his early years he distanced himself from contemporary neo-Thomists because they tended “to bifurcate philosophy and theology into completely separate disciplines and then present the Catholic faith as something consistent with scientific reason.” For Ratzinger and his Communio colleagues, the challenge confronting the Church “was not so much poor philosophy, but competing humanisms.” While they found Augustine and the Church fathers better able to respond to this need, they did not eschew Aquinas: ultimately they sided for what Rowland calls “the ‘Augustinian Thomism’ of Henri de Lubac.”

In addition to sketching the major themes of Ratzinger’s theology, Rowland details his relationship to Pope John Paul II, his theological consistency, and attempts by others to label his thought. In the twenty-four years Ratzinger worked at John Paul’s side, the two “stood shoulder to shoulder” on all the major theological and cultural issues they faced. Now, as Benedict XVI, “differences between the two pontiffs only appear when it comes to the narrower question of strategies for evangelizing contemporary culture.” Rowland insists that Ratzinger’s “fundamental theological orientation” has remained constant even though the theological climate of the Church changed radically since the council. This is a critical fact that defends him against charges of being both a liberal and a reactionary, depending on the particular perspective of the labeler. Yet the multitude of influences on his thought and his view of history and tradition defy the usual labels; Rowland settles on Adam Webb’s “cosmopolitan anti-liberal”: cosmopolitan since “he is open to new manifestations and developments” within authentic Christian culture, and anti-liberal since “he does believe that Christianity is the master-story and that the Catholic Church is a sacred institution, founded by Christ, to hand on the narrative from generation to generation.”

Both Nichols and Rowland offer similar readings and assessments of Ratzinger’s thought. With their different emphases, the two theologians illuminate the pope’s background, history, and influences, along with the full scope of his theological vision. Both conclude that at the center of Ratzinger’s theology is the person of Jesus Christ, whose self revelation, in the words of Nichols, occurred “to satisfy the deepest needs of human subjectivity.” The pursuit of the truth as revealed in Jesus Christ, not the building of a philosophical or moral system, has animated the theology of Joseph Ratzinger from the beginning, and this pursuit continues in the pontificate of Benedict XVI. For this reason Rowland concludes “that even though he is probably one of the most intellectual popes in history, for him Christianity is above all a matter of the heart.”

David G. Bonagura, Jr. is an associate editor of The University Bookman.