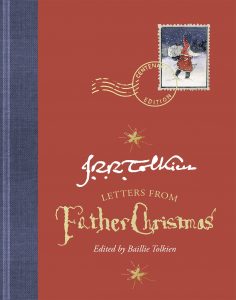

by J. R. R. Tolkien

Houghton Mifflin Company, 2020.

Hardcover, 208 pages, $28.

Reviewed by John Tuttle

The name Tolkien is first and foremost associated with what is widely acknowledged as the man’s chief literary creation, The Lord of the Rings. The writer’s mind vibrantly fleshed out Middle-earth in history, in phonetics, in flora, and in verse. Certainly, there was rather little that his creation lacked. It became a realm as genuine in the reader’s eyes as it was in Tolkien’s.

What is perhaps not discussed frequently enough is the influence J. R. R. Tolkien’s family had on his literary work. He was content at home, and he was well-situated among his loved ones. His writing became a twofold labor of love: passion both for his family and for the intrigue of language.

George Sayer, who knew Tolkien on a personal level, shares an insider’s look at the joy and devotion with which the author conducted his family affairs in “Recollections of J. R. R. Tolkien.” (The essay can be found within the gathered writings of Tolkien: A Celebration, edited by Joseph Pearce.) While not the essay to display the most eloquence or depth out of those accumulated in the collection, Sayer’s article provides the context needed by any reader of the Letters from Father Christmas.

His contentment in “domesticity,” as Sayer put it, is what facilitated so much of the “homely” nature and defense of the homestead depicted, especially through Hobbits, in his primary novels. Tolkien’s “love for children and delight in childlike play and simple pleasures,” writes Sayer, “was yet another thing that contributed to his wholeness as a man and the success of his books.”

A most beautiful example of his familial tenderness comes in the fictitious but wonderful relationship he presents most vividly in The Silmarillion through the love of Beren and Lúthien.

Tolkien admitted that his wife Edith was the direct inspiration for the character Lúthien. Out of the noticeable relationships built upon eros that find their way into the Middle-earth saga, that of Beren and Lúthien is unique not only for its potency but for the fact that it grows into endearing legend. It is a love story that continues to be heralded many generations after their passing—so goes Tolkien’s relation. And back in reality, when Edith passed away, her loving husband had “Lúthien” etched into her tombstone, where a number of years later after his own death, “Beren” was added.

Storytelling was seemingly inseparable from the Tolkien household. Intrigued by fantastic and entertaining tales since his youth, Tolkien bestowed his honed charm and acute attention to detail upon any and all of his fictional creations.

His son Christopher Tolkien, who died in January 2020, was a life-long advocate for the author’s body of work and often served in an editorial capacity on accumulations of his father’s writings. Having the genetic tie with his father was not what made Christopher an opportune editor for such a major portion of J. R. R. Tolkien’s work. Rather, it was his familiarity with his father and with his father’s writing style.

As William Ready observed in Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings, “Christopher Tolkien … was with the Royal Air Force in South Africa when The Lord of the Rings was in early process of subcreation, and although his father sent him drafts to read, he is sure that no comments of his made the slightest difference.” Frankly, not even those whose opinion Tolkien highly revered had much to do in changing the author’s mind about his stories.

Fragments of the great Middle-earth trilogy were not the only tidbits Christopher gleaned from the masterful storyteller. Long ago, on a chilly day in late December 1925, the children of Edith and John Ronald Reuel Tolkien gathered to hear a letter that must have been read aloud, which appeared in the crisp but wavering penmanship of old Kris Kringle. Its closing lines address the couple’s boys:

If John can’t read my old shaky writing (one thousand nine hundred and twenty-five years old) he must get his father to. When is Michael going to learn to read, and write his own letters to me? Lots of love to you both and Christopher, whose name is rather like mine.

Little Christopher, who was then barely past twelve months old, didn’t know it at the time, but he was going to grow up with a dad and a certain Father Christmas who shared one and the same love for him. Notice how he uses the simplicity of the present year to mark the age of old Nicholas Christmas. This isn’t the only time he would employ the trick, and Father Christmas himself eventually confessed he had lost track of his own years.

Within these Christmas letters, we see Tolkien outline a simple story—but a fun and adventurous one—submitted not to professional scrutiny but for the enjoyment of his family. Often accompanying the letters were colored drawings of the various adventures going down at the North Pole. These, of course, were supplied by the author, whose genuine talents for illustration were aptly portrayed in Dome Karukoski’s biopic Tolkien (2019).

Though Tolkien had been writing these for his children for several years already, the 1925 letter is also an outstanding specimen from the collection of Letters from Father Christmas in that it introduces the little Tolkiens to a new character, one beloved and long-lived after his inaugural appearance—the “North Polar Bear.”

The North Polar Bear (whose seldom-used real name is Karhu), when he is not accidentally wreaking havoc for Father Christmas, is hijacking his letters and adding his own commentaries amid Santa’s ramblings. Eventually, Father Christmas’s Elf-secretary Ilbereth (not to be confused with Elbereth, an Elvish title given to the Middle-earth character Varda—considered one of the Great Ones) joins in the social and artistic jabs scribbled all over the big man’s letters.

For any reader of Tolkien’s main body of work, this collection makes an engrossing read, one both refreshing and simultaneously familiar. Being jolly, the man up North nearly always happens to make his letters amusing, brimming with comical Polar Bear follies and present-packing tragedies.

Father Nicholas Christmas is a staunchly Christian individual though, as he explains, neither he nor his own dad Grandfather Yule can claim to be the original St. Nicholas of Myra. They were only namesakes of the genuine article. Nevertheless, Tolkien’s fond character adds to the disputed Santa canon (if there can be such a thing) as much as the contributions made by American writers like L. Frank Baum and Clement Clarke Moore. The Christian identity of Tolkien’s character exudes most noticeably from his use of liturgical feasts such as Michaelmas and St. Stephen’s Day to provide temporal approximations in relating the news occurring up near the North Pole.

Father Christmas, by all accounts, has the likeness of any fine wizard of Middle-earth. He enjoys his fireworks and fizzling “crackers,” and no doubt he is imbued with Christmas magic. Indeed, one is tempted to read him as a sort of Gandalf but with an extra portion of mirth. Any connoisseur of Tolkien’s well-known works will, in reading the Letters from Father Christmas, find himself making an array of comparisons with other known characters.

As for Polar Bear, he has a love for baths that could cheer the hearts of Bilbo and Pippin, who composed and sang ballads praising the simple comfort of a steaming bath. While Karhu’s days slip lazily by, in between his assisting Father Christmas and being the cause of many a haphazard accident, he happens to have a courageous spirit. Against goblins, Polar Bear is likely as formidable a foe as Beorn. In appetite, he has a soft spot for honey like so many bears, but also for Turkish delight, not unlike a certain Edmond Pevensie.

The similarities and influences these imaginary works shared with a context outside of The Lord of the Rings should be duly noted, particularly those involving the Man in the Moon. The character shows up on merely a few occasions from the looks of the letters addressed to the youthful Tolkiens. It is, nevertheless, interesting to observe that this does not constitute the last body of work in which Tolkien explores the character.

After having a cameo in a 1926 Father Christmas letter, the Man in the Moon becomes a bit more of a focus in the 1927 letter in which he comes to visit Father Christmas (as opposed to the previous year when he fell from the Moon into Santa’s garden following a powerful fireworks display). The lunar resident has an affinity for alcohol. After some brandy, the old Man in the Moon becomes quite drowsy and passes out. He also has a thing for plum pudding, a delicacy that he consumed promptly before trying the brandy.

Of course, like so many happenings up North in these stories, something harmless easily turns into a mess. After being away from the Moon for an extended time (asleep), the Man must return to restore order there, especially amid an outbreak of dragons, which dwell in holes in the Moon.

Tolkien’s two poems highlighting the mythical figure are found in The Tolkien Reader, published several decades after the final Father Christmas letter had been penned, and carry relevance to Middle-earth canon, having Hobbit origins. In “The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late,” the issue of drinking is a theme threaded throughout. And in “The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon,” which has an array of wordplays such as “lunatic” and “moonshine,” we read in the final four lines:

For puddings of Yule with plums, poor fool,

he arrived so much too soon:

An unwary guest on a lunatic quest

from the Mountains of the Moon.

What does this mean? Apart from realizing this was a character Tolkien was fond of, much is left up to the reader’s imagination. But I am somewhat partial to the notion that perhaps Tolkien’s children, Nicholas Christmas, and the Man in the Moon, and the Hobbits lived on a single plane of existence, that Middle-earth is not bound by any fixed parameters limited to a bygone country. It is endearing to ponder the stuff of children’s dreams and to consider that our fantasies, even now, hold the very same magical hope.

While Dickens may have his ghosts and grouches, Tolkien’s Yuletide landscape comes replete with goblins. They seem to be one of the biggest threats to Christmas. For some stories thrust into a landscape of flurries and snowdrifts, their monsters must be as dense and as dull as the snows in which they hunt. But for Tolkien, even up North, the foul things are those inhabiting the dark places beneath the world.

The cave goblins of this frigid country, who beat upon their war drums with as much vigor as those in Moria, steal from Father Christmas’s wares and waylay his home at Cliff House. But with Polar Bear’s aid, all is soon reorganized and on the mend.

The North Pole is not all bears and goblins, however. What would Nicholas be without his reindeer? Not all are aware that reindeer come from Lapland and that wizards dwell quite comfortably there, but Tolkien is quick to set us straight.

While the appeal of the characters spread throughout his Christmas letters is hard to ignore, Tolkien’s craft itself can’t be neglected either. Leave it to a philologist to develop a goblin alphabet for the amusement of his children, and leave it to the creative to project his verse-crafting talents onto Father Christmas and his wobbly hand.

Tolkien put much of himself and what was on his heart into these letters, treating them with the same care as any of his other works—if not more. As Father Christmas, he shares the excitement other children have had over the prospect of receiving copies of The Hobbit as gifts (as mentioned in a 1937 letter to the children). He further encourages his children in the areas of literacy, sharing, and selflessness.

This “horrible war,” as he writes on more than one occasion of World War II, is so far-reaching as to even affect the wares in the cellars of Cliff House. Father Christmas himself laments over the extreme poverty facing children the world over and the inadequacy of the materials at his disposal. With this, he evokes a message similar to that of author Kate Seredy’s climax in The Good Master (1935). Both Seredy and Tolkien invite the young during Christmas time to recognize the needs of others and offer up their gifts to those in greater need, putting the good of another before themselves.

Hence, Tolkien instills in his children a sense of administering the corporal works of mercy and even, closer to home, of sharing gifts among siblings. Greed, after all, is the mark of a goblin.

In their entirety, the Letters from Father Christmas shed deeper light into who John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was and what his family atmosphere was like. Certain to be enjoyed by any reader of The Lord of the Rings, they carry with them their own wit and grace.

John Tuttle has written for The Hill, Culture Wars magazine, The Millions, Starting Points Journal, Catholic Journal: Reflections on Faith & Culture, Eucatastrophe, and the University of Notre Dame’s Grotto Network. He contributed a chapter to the book The Right to Believe (Vide Press 2020). He has also served as the prose editor for Loomings, the literary magazine of Benedictine College.

NEH Support

The University Bookman has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.