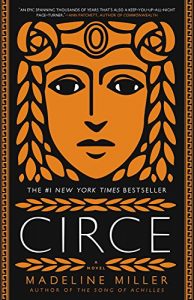

by Madeline Miller.

Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

Hardcover, 400 pages, $27.

Reviewed by Colleen M. Curran

Madeline Miller’s 2011 debut novel, Song of Achilles, presented a recasting of Homer’s Iliad that retold the familiar tale from the perspective of Patroclus, Achilles’s supposed lover. For her sophomore novel, Circe, Miller returns once again to Homer for inspiration, this time, the Odyssey. She brings Circe, the sea-witch who is largely a marginal figure and perhaps most memorable for turning Odysseus’s men into pigs, from the periphery into the spotlight. Miller’s Circe presents a feminist and insightful refashioning of familiar Greek and Roman tales, in which a marginal character who has less than thirty lines of dialogue in Books Ten through Twelve of the Odyssey recounts a personal, retrospective coming-of-deity narrative. While Homer appeals to the muse to help him sing of the man of many devices, Miller asks not for help in song, but “How would the songs frame the scene?” And it is with this mindset of reshaping and reinterpreting the sources that her Circe challenges a narrative previously dominated by men.

“Why pigs?” Odysseus asks Circe. This is a question that perhaps all readers (and listeners) of Homer’s Odyssey have asked themselves at least once—why does Circe change his men into pigs, of all things? The question of pigs is not central for Miller; the better question—and the one she explores—is why and how Circe ended up isolated on the island Aeaea as a witch. She answers by exploring Circe’s background, which takes us back to the halls of Helios, Circe’s father.

Ultimately, Circe’s story is one of loneliness because of difference—at first forced upon her, but then chosen deliberately. Circe is different from the other nymphs—she has yellow eyes and a thin voice. Her sister, Pasiphaë, is considered more beautiful than her, and her two brothers, Perses and Aeëtes, are considered more crafty and more statesmanlike, respectively. Circe is further separated from her family for her interest in humanity and mortality. The other gods and nymphs cannot stand the sight of humans, but Circe is intrigued by these mortal creatures. A dialogue with Prometheus before his trial proves to be a turning point for young Circe because Prometheus is the first to tell her the wonders of humanity. Circe also becomes isolated from the other nymphs and deities in Oceanus’s halls by her attention on the development of her sorcery. Banished for being kind to Prometheus, Circe is destined to live a solitary life on Aeaea.

But we see Circe channel this loneliness into creating an independent place for herself in which she can explore her main interests—humanity and witchcraft. Circe creates a paradise and cultivates her craft. She is hospitable to those who reach her shores. It is only when her hospitality—and Circe herself—is taken advantage of that she begins to turn men into pigs. With this knowledge, Circe and her actions make sense. She is not turning men into pigs for sadistic enjoyment but in revenge for crimes against her body and her island.

Miller’s mastery of her craft shines in imagining how these gods, demigods, and humans interact with one another. Perhaps this is most apparent in the meeting of Circe and Penelope, an episode that seems to be inspired by the now-lost Telegony. By all accounts, these two women should hate each other—Circe has not only slept with Penelope’s husband, but her son Telegonus also accidentally kills Odysseus. Instead, Miller paints a different picture, in which the two women realize that they have both lost the man they loved, but both women also realize that they each loved a different man. Penelope seems to have accepted that her Odysseus was long lost to her, even from before when he sailed to Troy.

Penelope is crafted in a different manner than the female deities peppered throughout the narrative. Whereas Athena is vengeful and quick-tempered and Medea is rash and deceitful in her actions, Penelope, the fully human woman, is considerate and slow to judgement. This is an interesting parallel with which Miller plays throughout Circe—the gods are mercurial and act without much thought; the humans are generally more thoughtful and slower to act. Circe and Penelope mourn and grieve for Odysseus together, something that we would never expect of Hera and Athena, for example.

In addition to this relationship, Miller seamlessly weaves in other familiar characters, such as Scylla, Hermes, Daedalus, the Minotaur, and Jason and Medea. Many authors would struggle to maintain their grip on the plot and narrative structure with such a cast. Miller, however, confidently weaves these episodes together to inform the reader about who Circe is, how she came to be this way, and what the future might hold for her. In doing so, Miller also presents us with more information about other characters. Her Daedalus, for example, is presented as a caring, considerate architect who is ultimately concerned with the welfare of his son—a far cry from, say, Joyce’s interpretation of the Daedalus myth. Hermes is presented as a fleeting character who deliberately creates problems, as opposed to being merely a messenger of the gods. These two-dimensional characters now have life, motive, and purpose in Miller’s tale.

Circe reflects: “[h]umbling women seems to me a chief pastime of poets.” Yes, there are liberties taken with the text and with the mythology in Miller’s Circe. But the novel is not meant to be canonical. Instead, Circe shows another perspective, one that is mostly—if not completely—absent from the canon itself. Overall, Circe is a creative endeavor that breathes fresh air into myths that can seem often to concern only the men. Circe finally speaks, and the version that Miller presents is one worth waiting for, even if it took a few millennia.

Colleen M Curran is a researcher of Anglo-Saxon poetry and paleography at the University of Oxford, where she is a Junior Research Fellow at Corpus Christi College and a member of the Consolidated Library of Anglo-Saxon Poetry project.