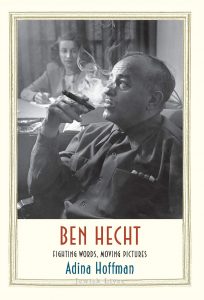

by Adina Hoffman.

Yale University Press, 2019

Hardcover, 264 pages, $26.

Reviewed by Carl Rollyson

Ben Hecht is one of those American writers who seems to have had a hand in everything. He was a Chicago newspaperman who also had designs on becoming a modernist artist published in Harriet Anderson’s prestigious Little Review (1914–1929). He authored an acclaimed sexually explicit first novel, Erik Dorn (1921) about the rise of a Chicago newspaper reporter modeled on himself. Called the greatest screenwriter by no less than the revered Pauline Kael, this Shakespeare of Hollywood became the most controversial propagandist for a Jewish homeland and the nascent state of Israel. Everyone read Hecht and read about Hecht and all sorts of writers and movie stars wanted to work with him. “Can you get me Count Bruga?” William Faulkner, writing from home in Oxford, Mississippi, asked his editor Hal Smith. Published in 1926, the novel, a satire based on Hecht’s friend, the flamboyant poet/critic Maxwell Bodenheim, featured a sendup of the bohemian Greenwich Village that Faulkner and a generation of writers sampled and savored. Hecht came with the imprimatur of publisher Horace Liveright, then signing on America’s literary greats like Theodore Dreiser and Eugene O’Neill, not to mention that notable first novel, Soldiers’ Pay. Hecht was still a force in the 1950s when Marilyn Monroe turned to him to ghost her autobiography.

Starting as a fledgling reporter making up some of his stories, Hecht, with the encouragement of his friend, screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, led a generation of writers to Hollywood and often collaborated with many of them. He worked, it seems, on hundreds of films—credited and uncredited so long as he remained highly paid. His great successes include The Front Page (1931), which became the very template of the newspaper movie; Scarface (1932), which set a high style bar for gangster movies; Twentieth Century (1934), one of the first superb screwball comedies); many historical epics and dramas such as Gunga Din (1939) and Wuthering Heights (1939); and important work with Alfred Hitchcock: Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946). Through all these heady years Hecht never stopped complaining about Hollywood’s meretricious values. Hecht, by his own lofty literary standards, was whoring and he wanted the world to know it—to know he was better than that. He set the tone for writers with literary aspirations who did not come to Hollywood unless they were desperate or deluded—like F. Scott Fitzgerald, who thought he could employ his superior style to uplift Hollywood scripts and cash in at the same time.

Hecht’s story is hardly new to biography, and Adina Hoffman gives full credit to her predecessors. Since her book is part of the Yale University Press series about Jewish lives, she focuses on his virtually demonic drive to awaken America’s conscience as millions of Jews perished in the Holocaust. His story remains important not only for what it says about America at the time but about the role Hecht thought a writer as propagandist could play. He did not simply point out the evils of fascism, he excoriated his fellow Jews in Hollywood and elsewhere for not making the Holocaust their main concern and basis of action. A goad, a Jeremiah, Hecht simply would not let up. As a result he developed a reputation as a dangerous zealot. He damaged his reputation in Hollywood and abroad and suffered blackballing in England and, for a time, in Hollywood as well.

Hoffman tells this story with verve and empathy, not neglecting Hecht’s faults but also exposing how pusillanimous many American Jews were in their efforts to assimilate and not to offend their fellow Americans by aggressively working on behalf of the dying Jews in Europe and the Zionists fighting for a homeland. For many of his fellow Jews, Hecht went too far, supporting Jewish terrorists working to expel Britain from Palestine. Hoffman prefers not to judge Hecht but to fairly present evidence that readers can assess for themselves.

Hoffman’s narrative portrays a man given to extremes in a world of extremity. His Jewishness did not seem to mean that much to him until the ascent of fascism in the 1930s. By 1939, Hecht knew where Hitler was headed. By 1943, Hecht understood that millions of Jews were being exterminated. He did not have to wait to see newsreel footage of the liberated concentration camps. Hecht, Hoffman might have emphasized, was a witness to a history that others simply did not want to confront. She might have spared a sentence for his heroism, although an argument can be made for, again, letting readers form their own judgments.

Hecht was most seriously a Jew when Jews were attacked. But he was not religiously observant and never visited Israel. His devotion to the Zionist cause deserves, perhaps, even more attention than Hoffman allots. As a biographer, she might have gone beyond the question of character to ask why Hecht was so driven to risk his Hollywood paycheck. Did his Zionism, his politicking, become a way of asserting his authenticity, of proving that he was indeed more than the sum of the Hollywood fantasy productions he had written into existence? Was his propagandizing a way for him to script himself into real events? There is probably no way for a biographer to answer such questions. But why not raise them? Why not say Hecht’s Zionism may have been his way of making his life count beyond the confines of Hollywood scripts?

Hecht remained, into the 1950s, a force, becoming a television personality taking on important personages and issues on his own interview show. As in Hollywood, he was sometimes frustrated. He was forbidden, for example, to discuss Norman Mailer’s controversial essay, “The White Negro.” Mailer and Hecht might have broken new ground in a new medium. To be sure, Mailer learned a good deal from Hecht, paying an amusing tribute in Marilyn (1973) to “Marilyn ben Hecht.” Mailer knew that behind the scenes Hecht had worked with Monroe on her autobiography. The project began as a much more candid story than most Hollywood biographies of the time—so candid in fact that after her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, Monroe withdrew from her collaboration with Hecht since she was revealing more than just the cleavage that Joe DiMaggio wanted for himself. As a result, Hecht never was able to finish the job of separating fantasies from facts in her life. It might well have done her some good to continue working with Hecht, who had such a good bullshit detector—a device that Hemingway said all good writers had to possess. But a short biography slotted into a publisher’s series, does not have the luxury of pursuing such speculations.

Hoffman does exceptionally well in what might be called a made-to-order biography. She writes with a fluency and sensitivity that makes her book one of the very best in the Jewish Lives series.

Carl Rollyson is the author of Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress, revised and updated (2014), Norman Mailer: The Last Romantic (2017) and the forthcoming The Life of William Faulkner.