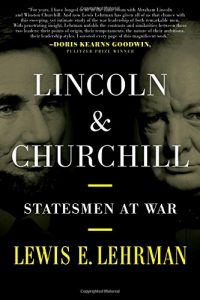

by Lewis E. Lehrman.

Stackpole Books, 2018.

Hardcover, 526 pages, $35.

Reviewed by Chuck Chalberg

Studies abound on Lincoln and Churchill. And why not? Each statesman deserves the attention he has received and will continue to receive. But a single volume devoted to the wartime leadership of both men? What a marvelous idea. And now that Lewis Lehrman’s idea has become a book, similar studies are not likely to abound, at least not if the subjects are Lincoln and Churchill and their respective wars.

Dual biographies, or at least dual biographies of a sort, can be quite compelling, especially if the subjects are contemporaries and rivals. John Milton Cooper’s The Warrior and the Priest (on Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson) comes to mind. Such books also have a place if the focus on the two contemporaries is concentrated on a single theme. Thomas Ricks’s book on the wartime roles of Churchill and George Orwell is a recent example.

By substituting Lincoln for Orwell, Lewis Lehrman has sacrificed the contemporary connection. And he has actually written something less than a full dual biography, choosing instead to dwell on their wartime leadership. Still, he cannot avoid backward glances that lend biographical heft to the project. Organized first by themes within the theme and then by a year-by-year comparison, most chapters jump back and forth between the two men. The result can be disjointed at times, but on balance it works.

If there is an overriding theme to the entire effort it is this: Lincoln and Churchill, while very different men overseeing very different wars of national survival, possessed similarly crucial qualities, including the strategic vision necessary to achieve victory. Adding drama to the story is the fact that each was an “unlikely” candidate for leadership and each assumed command at a time when the survival of his nation was very much in doubt.

Of course, both could have cut deals with their adversaries. Lincoln might have simply let the Confederacy continue to exist as an independent nation. And Churchill might have conceded control of Europe to Hitler in exchange for the continued independence of his island nation, plus continued control of its empire. Neither leader, so far as we know, ever entertained the possibility of following such a course. Neither was interested in pursuing the appeasement policies of his predecessor. In fact, despite setbacks and outright battlefield defeats, each held firm to the unconditional surrender of his foe.

Lehrman has relied primarily on secondary sources in preparing and writing this book. His original contribution resides much more in the conception and plotting of his project than in any discovery of new sources or exploration of those already known. And a plot line there is. Victory was no sure thing for either Lincoln or Churchill. Of course, we all know that victory was achieved, but Lehrman takes ample opportunities to remind his readers that neither Lincoln nor Churchill could know what we now know. While Lehrman does not go so far as to assert that each leader was indispensable to his country’s victory, he often seems to be sorely tempted to pronounce such a verdict. Modest as he is (as Lincoln was and Churchill was not), Lehrman prefers to stick to what can be known—and demonstrated. And judicious as he is (as both Lincoln and Churchill could be), Lehrman does not hesitate to offer his carefully considered views on the strengths and weaknesses of each man.

In his judgment the strengths of each leader far outweighed his weaknesses. In Lincoln’s case, “his intimacy with public sentiment, his adherence to principle, and his genius for argument informed his vision and his ambition …”

When it comes to Lincoln’s weaknesses Lehrman prefers to give the platform to others. For example, Henry C. Whitney, a friend and fellow lawyer, deemed Lincoln to be “one of the most uneven, eccentric, and heterogeneous characters … that ever played a part in the great drama of history …”

As we shall see, Lehrman is much harsher in his treatment of the much more mercurial and more ego-driven Churchill. What could be both a strength and a weakness in both men was that each in his own way was a loner. As such Lehrman concludes that each was “much more secure in (his) own judgments than in the opinions of conventional experts.”

What nudges their loner designation into the strength column is Lehrman’s contention that both Lincoln and Churchill were men of solid character and great resilience. Both traits are obviously crucial to successful leadership. The same can be said of their talent for writing for the ear, a talent each honed by hard work, which Lehrman regards as further evidence of their sterling character.

Lehrman does not shy away from declaring both to be men of considerable, perhaps even consuming, but not all-consuming, ambition. They were also patriots, pure and simple. As such, they instinctively put their country’s interests ahead of their own. There was a time when that quality and commitment—and set of priorities—would have been presumed to be minimum requirements for national leadership. Not so in our much more cosmopolitan and highly individualistic age.

One more common quality must be mentioned, because Lehrman returns to it more than a few times: neither Lincoln nor Churchill was a moral relativist. Therefore, neither leader “harbored illusions about the nature of evil.” Once again, Lehrman has hit upon a leadership quality in short supply in our western world of overarching cosmopolitanism and hyper-individualism, not to mention creeping, nay surging, secularism. While Lehrman concedes that neither man was an orthodox Christian, he refuses to see either of them as a thoroughly, or even a primarily, secular figure. Lincoln had steeped himself in the Bible, while Lehrman contends that both leaders had a real sense that Providence was at work in their lives.

At the same time, neither man was a moralist or a moralizer. Nonetheless, both thought in terms of right and wrong, good and evil. Lincoln had long been convinced of the evil of slavery and its spread. And shortly after Hitler’s rise to power Churchill was speaking out against the evil of Nazism and its potential spread.

Their willingness to label real evils and speak against them made Lincoln and Churchill anathema to the elites of their day. Lincoln was surely that to the southern planter class, as well as to the elite of Washington, DC, and the political leadership of both his upstart Republican party and the entrenched northern Democrats. Lincoln, the country bumpkin, was to be deplored, even if he could not be ignored.

Of course, Churchill was a member of the British elite. But he certainly had enemies within the elite of his own party. That would be the Conservative party that he left and would subsequently rejoin. “Anyone can rat,” he once shrugged, “but it takes ingenuity to re-rat.” No doubt both his ratting and re-ratting assured that he would have more than his share of enemies in both parties.

What was far from assured was that either man would ever hold the reins of power, much less that they would be supreme leaders at moments of supreme crisis in the history of each nation. Most of Lehrman’s book deals with their exercise of power once the “unlikely” designation was removed. Here stark differences between the two emerge. These differences did not ultimately prove to be significant differences in the great scheme of things. One of the two was “not always a deliberate and disciplined listener.” He also lacked an “equable temperament.” More than that, he could be “impetuous, emotional, romantic, and self-centered.” Guess which one. Hint: His mother was an American, but his father was not. The other of the two was a very good listener and “seldom indulged his anger.” He was also an “untutored amateur” when it came to serving as a wartime leader. Guess which one. Hint: He was a teetotaler who didn’t smoke.

Actually, Lehrman reminds us that Churchill chewed his cigars and ordered his liquor to be watered down. Perhaps the more telling hint might have been that the “untutored amateur” pursued an anaconda strategy in winning his war. Lehrman, however, contends that both warlords actually subscribed to a similar “surround and squeeze” strategy. In addition, each leader focused on defeating enemy forces rather than capturing the enemy’s capital, whether it be Richmond or Berlin.

Each war leader faced multiple problems with his generals. Until the emergence of Grant, Lincoln’s problems were by far the more severe and protracted. One guesses that a congenitally impatient Churchill would have dismissed McClellan and others much sooner, and for good reason.

Each faced seemingly intractable political problems as well. Lincoln had to steer between the radical Republicans and the moderates and conservatives of both parties in the north. Churchill’s political and diplomatic problems were more numerous and more severe. As Lehrman puts it, he was “bound to consult” his coalition, while Lincoln was “at liberty to ignore” his cabinet.

As the war proceeded, Churchill was reduced to playing second fiddle to Franklin Roosevelt. Among other things, that meant following the lead of an ally/rival, who could not resist needling, even belittling, him. More to the geopolitical point, it meant that Churchill no longer controlled decision-making for the European theater of the war. At war’s end this also meant that Churchill had to defer to an American president who was unwilling to face, much less oppose, what Churchill saw as the looming Soviet threat to western Europe.

Thanks to John Wilkes Booth and the British electorate, neither warlord had the opportunity to preside over the transition from victory to peace, or from unconditional surrender to something far less harsh than that. And now thanks to Lewis Lehrman, we have this unique study of two very different men, men of very different backgrounds and experiences, men who were crucial, if not necessarily indispensable, to their country’s military triumphs in 1865 and 1945.

In sum, Lehrman’s book offers evidence in support of two propositions. The first is that successful wartime leaders do not come from a single mold, much less possess similar profiles or personalities. Secondly, despite their considerable differences Lincoln and Churchill shared qualities crucial to the success of democratic war leaders. Each summoned the strength of character necessary for the task at hand. Each understood the importance of perseverance, both for themselves and for those who would follow them. Each was a patriot who was confident of the rightness of his cause. And each had great confidence in his ability to work hard to communicate that rightness at a time of great peril for his nation.

In telling his story Lewis Lehrman demonstrates a kind of confidence of his own. He knows that he has a good story to tell, an unlikely story of “unlikely” and very different leaders. Lastly, he has confidence in his readers. He is sure that we will understand that the differences between Lincoln and Churchill, while making for a better story, amount to nothing when stacked against the fact that each leader proved to be the vitally important persevering patriot that his nation needed in the midst of war.

John C. “Chuck” Chalberg has written a dual biography of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey.